Tag Archives: Craig Anderton

Reinvent Your Stereo Panning

This tip is about working with stereo, NOT about Dolby Atmos® or surround—but we’re going to steal some of what Atmos does to reinvent stereo panning. Studio One’s Surround panners are compatible with stereo projects, offer capabilities that are difficult to implement with standard panpots, and are easy to use. Just follow the setup instructions below, and start experimenting to find out how surround panning affects stereo tracks. (Surround panners work with mono tracks too, although of course the stereo spread parameter described later is irrelevant.)

Setup

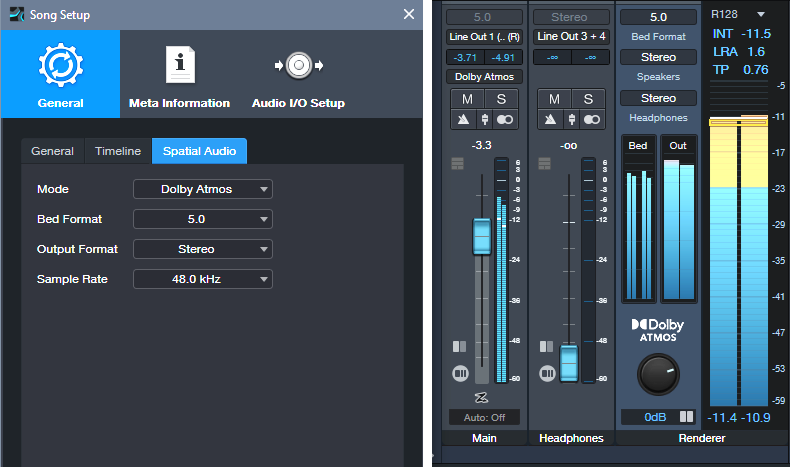

When you’re ready to mix, choose Song > Spatial Audio. Select the parameter values to the left in fig. 1. In the output section (fig. 1 right), select 5.0 for the Bed format, and Stereo for both Speakers and Headphones so you can use either option to monitor in stereo.

Figure 1: Parameter setup for Surround panning with stereo projects.

After choosing Dolby Atmos for spatial audio, channel panpots turn into surround panpots. Double-click on them to see the “head-in-middle-of-soundfield” image shown below. Choose Disable Center, which isn’t used. LFE Level doesn’t matter, unless you’re using a subwoofer.

Using surround panners for stereo offers several adjustable parameters:

Spread. Move the L and R circles to set the left and right pan position spread, or click and drag in the numeric Spread field. The spread (fig. 2) can go from 0 (mono), to 100% (standard panning), to 200% (extra wide, like binaural panning).

Figure 2: (Left to right) 14.8% spread, 100% spread, 200% spread.

Direction. After establishing the spread, click on the arrow and rotate the spread so it covers the desired part of the stereo field (fig. 3). You can also click and drag on the numeric Direction field. Between spread and direction, you can “weight” the stereo spread so that it covers only a sliver of the stereo field, covers center to right or left, mostly left, mostly right, etc.

Figure 3: (Left to right) Panned from left to center, panned to a narrow slice of the stereo field, and panned almost full but tilted toward the right.

Size. This has no equivalent with stereo panpots. Click on the arrow, and move it closer to the head for a “bigger” size, or further from the head for a “smaller” size (fig. 4). You can also click and drag on the numeric Size field. The result isn’t as striking as with true surround, but it’s much more dramatic than standard panning. Note the “cloud” that shows how much the sound waves envelope the head. All the previous images showed a small size.

Figure 4: (Left to right) Biggest size/least distance, moderate size/moderate distance, smallest size/furthest distance.

Flexible automation. A joystick or controller pad can automate two of the parameters simultaneously. Or, modulate all three parameters using three controls from a control surface. This is a huge deal compared to standard panning. For example, suppose an instrument is ending a solo, while another solo starts. The one that’s ending can pan to a narrower spread, move off to the side, and become smaller just by moving three controls.

Other Features

- Balance Tab. The surround panners can also serve as conventional balance controls. This setting interacts with the panners. For example, if the L and R buttons are close to each other, there won’t be much balance to adjust. I rarely use the balance option. To make sure that surround panning isn’t altered by a Balance parameter setting, check that the balance “dot” is in the center of the virtual head.

- Size lock. This maintains the same Size setting, regardless of what you do with the Direction and Spread parameters. Hold Shift to bypass Lock temporarily, and fine-tune Size.

- Object Panner. Right-click on the Surround panner, and you can choose an Object Panner instead. This is less relevant with stereo, because front/back and lower/higher directionality doesn’t exist like it does in a true Atmos system. However, the Object Panner does have Size, Spread, and Pan X (left/right) parameters, so feel free to play around with it—you may like the interface better than the surround panner. It’s also possible to do crazy automation moves. In any case, you can’t break anything.

- Other. This is another function you reach via a right-click on the Surround Panner. You’ll see a list of other plugins on your system that may have spatial placement abilities, like Waves’ Nx series of control room emulators, Brauer Motion, Ozone Imager, Ambisonics plugins, and the like. If you insert one of these, you can revert to the stock Studio One panners or choose other options by clicking on the downward arrow just under the “other” plugins name.

It may sound crazy to use Surround panners in stereo projects—but try it. You can truly do stereo panning like never before.

Presence Electric 12-String (the Artist Version Remix)

Presence’s sound library includes a fine acoustic 12-string guitar, but not an electric one. So, perhaps it’s not surprising that one of the more popular blog posts in this series was about how to create a realistic electric 12-string preset with Presence.

Unfortunately, that was before Studio One introduced Track Presets. The preset relied on a Multi Instrument, so it worked only with Studio One Professional. However, thanks to Track Presets, we can revisit our electric 12-string, and make a plug ’n’ play version that works for Studio One Artist as well as Professional (download link at the end).

Overcoming the Sampling Problem with 12 String Guitars

Sampling a 12-string is difficult. The sound is constantly changing due to the shimmering effect from slightly detuned strings. Furthermore, some notes are doubled with octave-higher notes, while other notes are doubled with unison notes. My solution is not to try and sample a 12-string guitar, but to construct one from three sets of 6-string guitar samples.

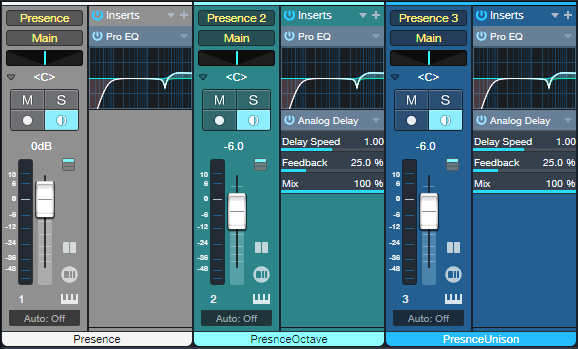

Each of the three Presence instances (fig. 1) loads the preset Guitar > Telecaster > Telecaster Open from the stock Presence library:

- One instance provides the main guitar sound.

- Transposing another instance up 12 semitones provides the octave-above notes.

- A physical 12-string guitar doesn’t have octaves on the 1st and 2nd strings, so the third Presence instance provides a unison sound for the higher strings.

Figure 1: With three instances needed to create a single instrument, note that all three Monitor buttons must be enabled to play the instrument from your keyboard or MIDI guitar controller.

Limiting Note Ranges

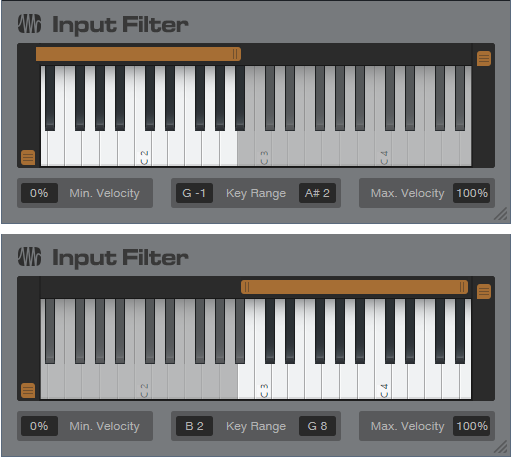

In the original preset, Multi Instrument Range edits prevented the unison sounds from overlapping with the octave-above sounds. In the Artist preset, two Input Filter Note FX restrict the ranges (fig. 2).

Figure 2: The upper Note FX Input Filter restricts the range of the octave-above notes to A#2 and below. The lower Note FX Input Filter restricts the range of the unison strings to B2 and above.

Emulating the 12-String “Shimmer”

A 12-string is never perfectly in tune, which gives a shimmering effect. The octave instance is transposed up +12 semitones, but the Pitch Fine Tune setting is +5 cents. The unison instance Pitch Fine Tune is -2 cents. This gives the chorus-like that’s inherent in 12-string guitars. Detuning the virtual strings provides a more realistic sound than trying to “fake it” with a time-based modulation effect.

About the Analog Delays

The higher string in a pair of strings plays just a little bit late, because your pick hits the main string before the octave or unison string. To emulate this effect, the Analog Delay (fig. 3) provides a 20 ms delay for the octave and unison instances. (We can’t use Presence’s Delay, because the mix needs to be 100% delay—no dry sound.)

Figure 3: Analog Delay settings used to emulate string pluck delay.

Without this delay, the emulated 12-string lacks realism. The Analog Delay also adds some High Cut to reduce some of the brightness caused by transposing the octave strings. The Width settings provide a big stereo image, but for a more “normal” sound, turn ping-pong mode to Off.

The octave and unison instance levels are -6 dB below the main guitar sound. With physical 12-string guitars, the octave strings are thinner than the strings that generate the standard pitch. So, they generate less output. Lowering the level of the octave strings gives a better overall balance. Technically, the unison strings could be at the same level, but their levels are also a little lower to avoid an unbalanced sound compared to the octave strings.

EQ Settings

The Octave and Unison string instances use Presence’s internal EQ to attenuate the highest and lowest frequency bands. The main instance attenuates the low band, but peaks +3 dB at 3 kHz. Regarding the Pro EQ3 settings, open up the preset if you want to deconstruct the programming. The main aspects are a bass cut to give a more trebly, “Ricky”-like 12-string sound, a high-shelf boost for a little extra brightness, and a narrow notch around 3.2 kHz to reduce some “string ping” inherent in the original samples. As always, though, adjust for your tastes in guitar tone.

So, Studio One Artist aficionados, what are you waiting for? Download the preset, and get ready to make some cool electric 12-string sounds.

Download CA 12-String Electric Artist.trackpreset here!

Faster, Simpler, and Better Comping

At first, this might not seem too exciting. But follow the directions below, and try comping using this method—I don’t think you’ll be disappointed. This tip shows how to:

- Audition, select sections of, and promote Takes while listening to the rest of the mix, at any level you want.

- Listen to the edited Parent track made up of the Takes you’ve promoted, at any time during the comping process. Again, this is in context with the mix.

- Do all of the above while looping, so there’s never a break in the editing process.

- Do comping with only the Arrow tool—you don’t need the Listen tool.

Preparation: Set Up Dim Solo

First, implement the Dim Solo function described in the blog post Super-Simple Dim Solo Functionality. Dim Solo allows soloing a track or tracks, while all the other tracks are at an adjustable lower level. The process works by assigning all tracks except for the one you want to solo (e.g., a vocal track with its Take layers) to a VCA channel. You can then “dim” all the non-soloed tracks with the VCA level fader to whatever level you want while you comp, and hear the Takes in context with the song. After auditioning and selecting the desired sections of your Takes, set the VCA fader back to 0.0 to return to the original mix levels. The minute or two it takes to set up Dim Solo is more than offset by the benefits it offers to comping. For more details, refer to this blog post for how to create the Dim Solo function.

Faster Take Auditioning, Selecting, and Promoting

After setting up Dim Solo and using the VCA Channel fader to adjust the level of the mix (which excludes the track being comped, because it isn’t part of the VCA group), here’s how to audition and select Takes:

1. Safe Solo (Shift+Click) the parent track with the Takes. This is important! It allows soloing the Parent track without muting the tracks that are playing back at the dimmed level.

2. Loop the section with the Takes you want to audition.

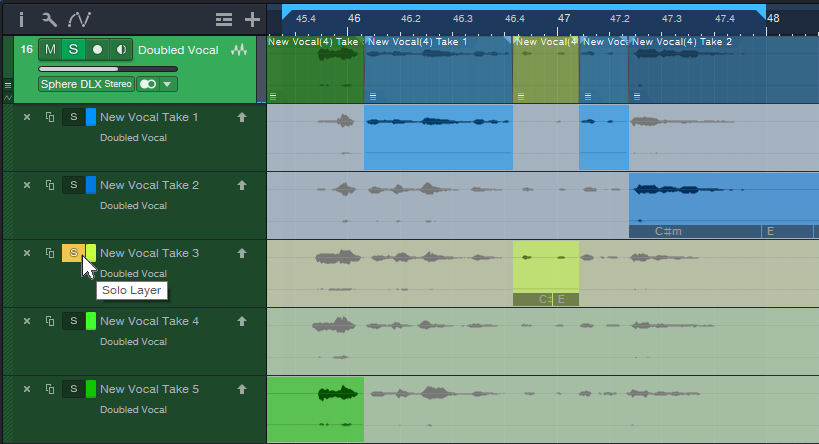

3. Click a Take’s Solo button to audition it while the song loops (fig. 1).

Figure 1: Take 3 is being soloed for auditioning, and for selecting sections to be promoted to the Parent track. Turning off the Take’s Solo would solo the Parent track, so you could audition the edited parent track and hear any Take sections that had been promoted.

4. If you hear a section in a Take you want to promote to the Parent track, use the Arrow tool (which turns into an I-beam cursor when hovering over a selected Take) to click+drag over the section.

5. Continue soloing Takes while the music loops, and select the sections you want to promote to the Parent track. If needed, alter the loop start and end points.

6. If at any time you want to hear the edited Parent Track with the Takes you’ve promoted up to that point, make sure no Take layers are in solo mode.

Better Music Through Better Comping

One reason I wrote up this tip is because of an interesting side effect. The Takes I selected as “best” when auditioned in the usual way were often not the same Takes chosen as “best” when listening to them in context with the music. A technically perfect Take is not necessarily the same thing as a Take with the best feel. Listening to, selecting, and promoting the Takes in context with the mix makes a big difference in helping to select Takes that fit the music like a glove.

How to Quickly Slash Your Latency

You know the feeling: You’re tracking or doing an overdub with a virtual instrument or amp sim, but you’re frustrated by the excessive latency inherent in complex projects with lots of plugins. And with older computers, latency may be an annoying fact of life.

Of course, Studio One has clever low-latency native monitoring. However, there are some limitations: plugins can’t introduce more than 3 ms of latency, FX Chains can’t use Splitter devices, and external effects using the Pipeline plugin are a non-starter.

This tip’s universal technique has only one significant limitation: it’s oriented exclusively toward having the lowest latency when tracking or doing overdubs. Fortunately, most of the time that’s when low latency is most important. Latency doesn’t matter that much when mixing down.

Here’s the process:

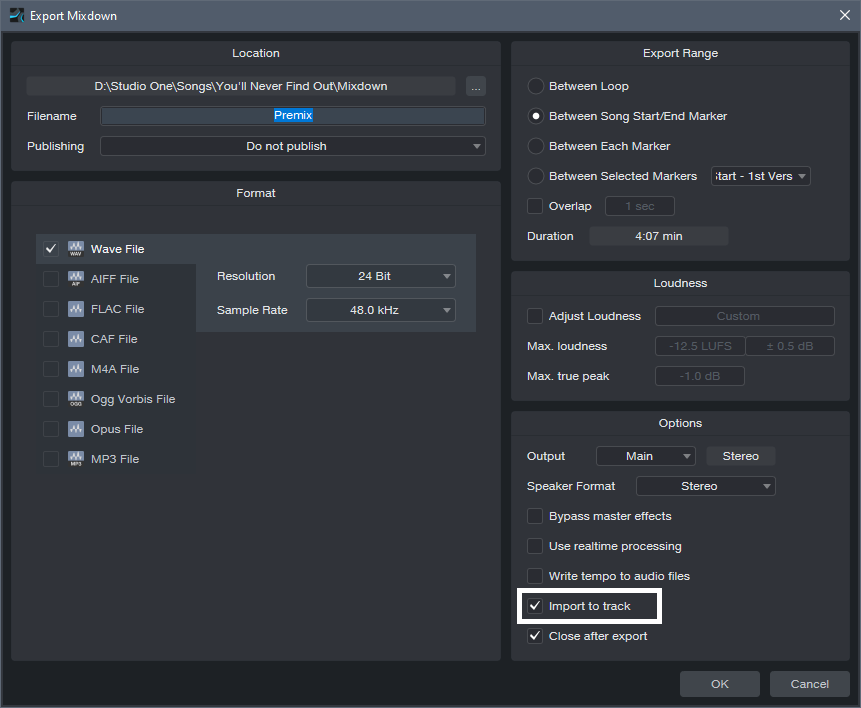

1. Make a premix of all tracks except the one with the virtual instrument or amp sim you want to track with or overdub. Do this by exporting the mix (Song > Export Mixdown) and checking Import to Track (fig. 1). The imported track becomes a premix of your tracks. Note that if any of the tracks use Pipeline, the premix must be done in real time.

Figure 1: The first step is to create a Premix of all your tracks. Make sure you select Import to Track (outlined in white).

2. Select all tracks except for the Premix and the one with the virtual instrument or amp sim you want to use for your overdub.

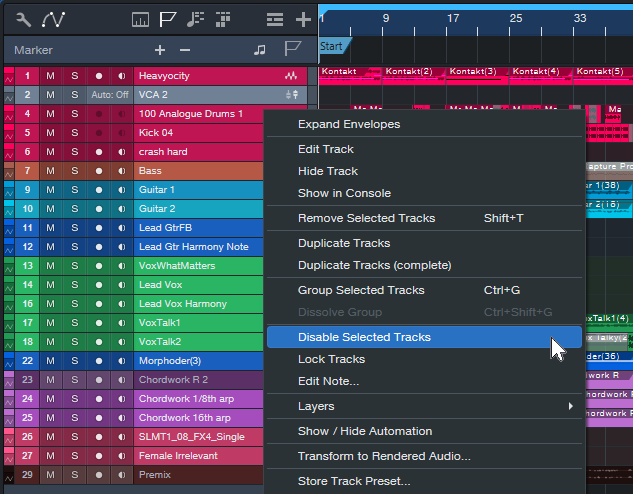

3. In the Arrange view, right-click on the selected tracks. Choose Disable Selected Tracks (fig. 2).

Figure 2: In this example, all the tracks are selected for disabling, except for the Mai Tai instance in Track 23 and the Premix.

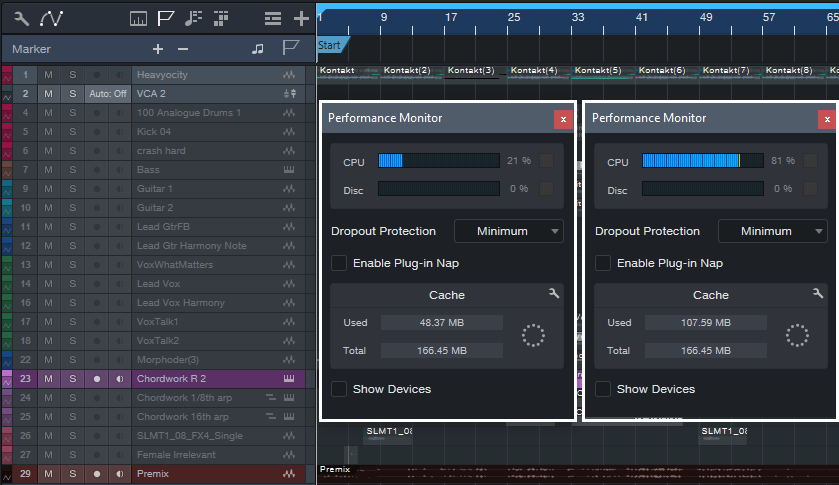

4. Now you can overdub or track while listening to the premix. Because there’s now so little load on the CPU (fig. 3), you can reduce the Device Block Size and Dropout Protection (under Studio One > Options > Audio Setup) to lower the latency.

Figure 3: The Performance Meter on the left shows CPU consumption with all tracks except the Mai Tai and Premix disabled. The Performance Meter on the right shows CPU consumption with all the tracks enabled.

5. While listening to the premix as your reference track, you’ll be able to play your virtual instrument or through your amp sim with much lower latency.

6. When you’re done with your overdub or tracking, you can delete or mute the Premix, and return the latency to a higher setting that allows for mixing without dropouts or other problems.

How to Fix Phase Issues

Recording audio using more than one feed from the same source may create phase issues. For example, when miking a bass amp and taking a DI (dry) input, the DI’s audio arrives at your interface instantly. But because sound travels 12″ (30 cm) in 1 millisecond, the mic’s audio will arrive later due to the distance between the mic and speaker. This means it won’t be time-aligned with the direct sound, so there will be a phase difference.

Miking an acoustic guitar with two mics, or drum overheads that are a distance from the drum kit, may also lead to potential phase problems. Even partial phase cancellations can thin or weaken the sound.

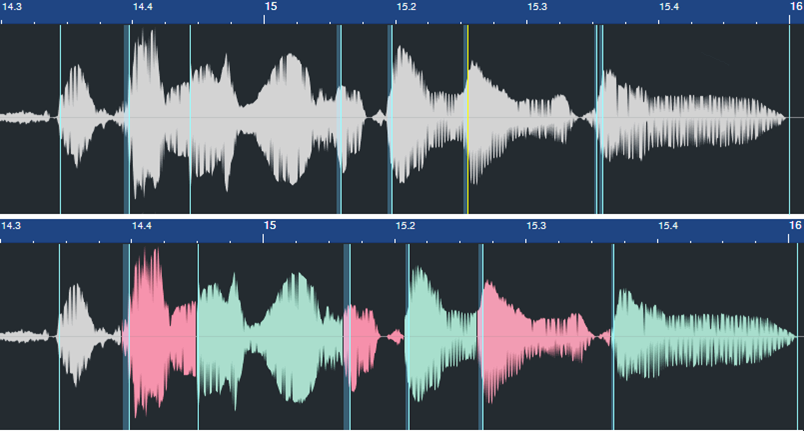

It’s best to check for phase issues and fix them prior to mixing. One way to resolve phase issues is to look at the two waveforms on the timeline, and line them up visually. However, the waveforms may not look that similar (fig. 1), especially when comparing audio like a room mic with a close-miked sound.

Figure 1: Despite being zoomed in, you wouldn’t necessarily know from the waveforms that they are at their point of maximum cancellation.

Another option is to sum the sources in mono, delay or advance one relative to the other, and listen for what sounds the strongest. That can work, but it’s not always easy to hear exactly when the waveforms are in phase. Let’s make the process more foolproof.

The Phase Correction Process

The goal is to find the alignment of the two waveforms where the audio sounds the strongest. However, it’s easier to hear phase cancellation than addition. So, by inverting the phase of one channel, we can align the tracks for maximum cancellation. Returning the phase to normal then gives the strongest sound. Here’s the process:

1. Solo the channels that may have a potential phase issue. Determine whether they do by listening for a thinner sound when they’re summed to mono, or both panned to center.

2. Match the channel levels as closely as possible.

3. Pan the two channels hard left and hard right.

4. Insert the Phase Meter plugin in the master bus.

5. Insert a Mixtool in one of the instrument channels. Invert the Mixtool’s phase. If a track uses stereo audio, invert the left and right channels.

6. Turn off Snap. This allows nudging an Event in 1 millisecond increments. Select the Event and type Alt+Right Arrow to move the track earlier by 1 ms, or Alt+Left Arrow to move the track later by 1 ms.

7. Nudge one of the tracks with respect to the other track until the Phase Meter shows the most negative correlation (i.e., the lower bar graph swings to the left as much as possible, as in fig. 2). This indicates maximum cancellation. Note: The time range for maximum cancellation is extremely narrow. One millisecond can make the difference between substantial cancellation and no cancellation. Be patient. Adjust 1 ms at a time.

Figure 2: A negative correlation reading indicates that the two sources have phase differences.

8. You’ve now aligned the two tracks. Remove the Mixtool plugin so that the two signals are in phase.

Tip: For audible confirmation, in Step 7 listen as you make these tiny changes. If you enable the Mono button in the Main bus, aim for the thinnest possible sound. If you monitor in stereo, listen for the narrowest stereo image.

Super-Fine Tuning

1 ms is a significant time shift when trying to match two signals’ phase. Step 7 will isolate a 1 ms window where the two tracks are in phase (or at least close to it), but you may be able to do better.

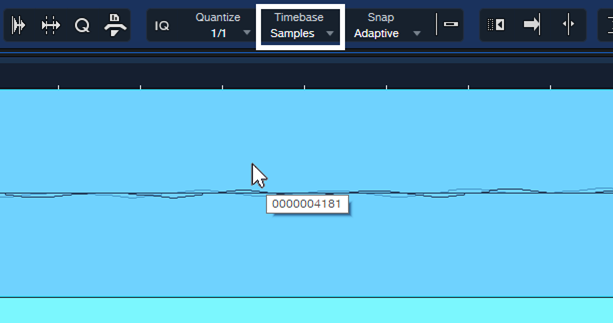

Select Samples for the Timebase and turn off Snap. Zoom in far enough, and you’ll be able to click on the Event and drag it earlier or later in 1 sample increments (fig. 3). That can tighten the phase further, if needed.

Figure 3: With Timebase set to Samples and Snap turned off, the resolution for moving an Event is 1 sample.

This may be overkill, but I know some of you are perfectionists 😊. Happy phase phixing!

Bigger, Wider Sounds: Try Stereo Miking

If you haven’t experimented yet with mid-side stereo miking, you’ll be in for a treat when you do. Here’s why:

- Record background singers with gorgeous stereo imaging

- Capture a guitar amp with stereo room sound

- Run synths and drum machines through a PA or amp, and obtain the vibe of recording electronic instruments in an acoustic space

- Capture full stereo with choirs, plays, podcasts, seminars…you name it

Even better, mid-side stereo miking collapses perfectly to mono, and Studio One Professional bends over backward to make the recording process easy.

Wait—Is This Déjà Vu?

The post Mid-Side Processing with Artist covered mid-side processing for Studio One Artist, and Mid-Side Processing Made Easy did the same for Studio One Professional. However, these were only about processing mid and sides audio extracted from an already recorded stereo track.

This post is about recording with mid-side miking, and monitoring the result as it’s being recorded. This lets you achieve optimum mic placement by hearing the results of changes in mic positioning, in real time. You don’t have to record the audio first, and then play it back to see if you got it right. And on playback, there’s no need to extract the mid and sides, because you already recorded them as separate tracks.

Mid-Side Recording? I’m Already Intimidated!

You needn’t be. You might have heard about mid-side recording requiring math, phase changes, encoding, decoding, a degree in physics, etc. Nope! As I said, Studio One Professional makes it easy.

There are many ways to record in stereo. The most common is X/Y miking, where one directional mic points toward the left, and one toward the right. But this technique is not ideal. Directional mics color sound coming in from outside the pickup pattern, and the two signals don’t play nice when collapsed to mono.

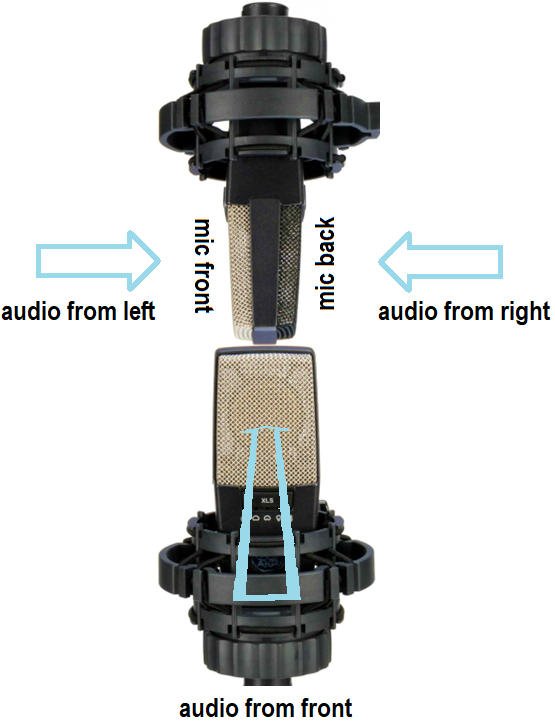

Mid-side miking uses a mic with a cardioid pickup pattern to capture the center of a stereo sound, and a mic with a bi-directional (aka figure-8) pickup pattern to capture the left and right sides. Ribbon mics inherently have a figure-8 pickup pattern, but there are also multi-pattern condenser mics that can be switched to a figure-8 pickup pattern. With this pickup pattern, the mic’s front and back pick up sound, while the sides don’t pick up any sound.

Fig. 1 shows how you’d set up the two mics for mid-side stereo recording. Pretend you’re a guitar amp looking at the mics. The top, figure-8 mic is mounted upside down because the diaphragms of the two mics need to be as close together as possible. The figure-8 mic’s side faces you. Its front faces to the left, and its rear faces to the right. Meanwhile, the cardioid mic is pointing at you.

Figure 1: Mid-side miking setup. (Mic images courtesy Sweetwater Publishing)

The Studio One Connection

You need two tracks and mixer channels, one for the cardioid (mid) mic and one for the figure-8 (sides) mic. Record the two mics like you would any other mics. However, this is where many people get lost—it’s counterintuitive that the single mic cable coming from the figure-8 mic can turn into right and left channels in Studio One. Fortunately, Studio One knows how to do this.

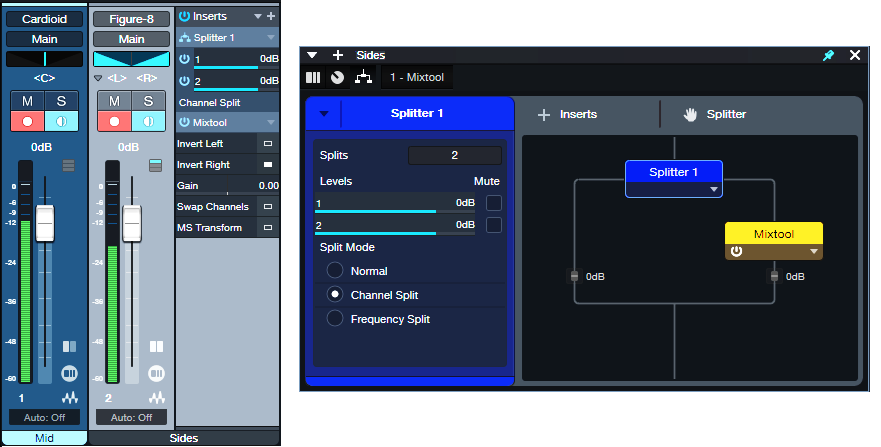

Figure 2: Studio One FX Chain for mid-side recording.

Fig.2 shows audio being recorded. Pan the Cardioid mic to center for your mid (center) audio. For the Sides mic, set the track input to mono, but set the track mode to stereo (important!). This combination allows recording in mono, but playing back in stereo.

A Splitter in Channel Split mode splits the mono audio into two paths. All the Mixtool plugin does is invert the right channel path’s polarity. Now the left and right channels are out-of-phase, so there’s a wide stereo spread. At the mixer, set the Sides channel’s Pan mode to Dual Pan. Pan the controls hard left and right. Now we have the Splitter’s left channel audio panned to the left, and the right channel’s audio panned to the right.

You might think “wait a second…if the left and right channels are out-of-phase, then if they play back in mono, they’ll cancel.” Exactly! And that’s why mid-side miking offers superb mono compatibility. When the sides cancel, you’re left with the mono audio from the cardioid mic, which also picks up sounds that are in front of the mic to the left and right. So, you’re not losing the audio that ends up being stereo—just the stereo imaging. And of course, mono audio has no problem being played back in mono.

Now, Here’s the Really Cool Part

You don’t have to understand how all this works, just create the setup described above. The Sides channel varies the level of the stereo image, and the Mid channel varies the mono center. So, you can make the stereo image wider by raising the level of the Sides channel, and lowering the level of the Mid channel. Or, lower the Sides channel for a narrower image. Or, process the two separately, and gain the advantages of mid-side stereo processing.

Go ahead—bathe your ears with stereo recording instead of mono. As long as you have one mic with a directional pickup pattern, one mic with a figure-8 pickup pattern, and two mic stands, you’re good to go. And there’s a bonus: if you start getting involved with Atmos mixing, having stereo audio gives you more fun options than mono.

How to Prioritize Vocals with Mix Ducking

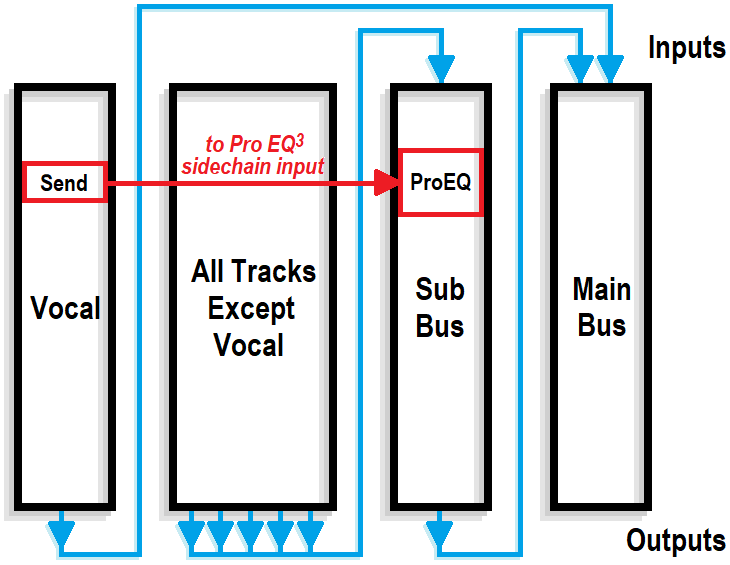

This complements the tip Better Ducking for Voiceovers and Podcasts and the tip Why I Don’t Use Compression Anymore. It applies the concept of voiceover ducking to your entire mix. Here’s the TL;DR: Insert the Pro EQ3 in a master bus, feed its sidechain from your vocal track, and adjust the Pro EQ3’s dynamic EQ to reduce the vocal frequencies in the stereo mix. When done subtly, it makes the voice stand out more, because the mix behind it stands out less.

Create a Secondary Main Bus

Inserting the Pro EQ3 in the Main bus won’t work, because the vocal goes to the Main bus. So, any dynamic EQ would affect the voice as well as the mix, which we don’t want. The solution is to create a secondary Main bus. We’ll call it the Sub Bus.

1. Select all your tracks in the mix (click on the lowest-numbered track and shift+click on the highest-numbered track).

2. Ctrl/Cmd click on the vocal track to de-select it. The other tracks should still be selected.

3. Right-click on one of the selected tracks and choose “Add Bus for Selected Channels” (fig. 1).

Figure 1: All tracks are selected except for the Vocal track (7). They’re about to be re-assigned from the Main bus to the new Sub Bus.

4. The new Sub Bus feeds the Main bus. Confirm that all track outputs go to the Sub Bus except for the Vocal track, which still goes to the Main bus. Now we can process the Sub Bus independently of the Vocal.

5. Insert a Pro EQ3 into the Sub Bus. Insert a Send from the Vocal track to the Pro EQ3’s sidechain. Fig. 2 is a simplified signal flow diagram.

Figure 2: All tracks except the Vocal go to the Sub Bus. The Sub Bus out and Vocal out go to the Main bus. A send from the Vocal track drives the sidechain of a Pro EQ3 inserted in the Sub Bus.

6. Now comes the most important part—choosing the optimum dynamic EQ settings. The goal is to add dynamic cuts at frequency ranges that correspond to the voice. The settings in fig. 3 are a good start for experimenting with this process:

- The Frequencies are set an octave apart

- The Ranges are at their maximum negative values

- The Q settings are 2.0

- The Sidechain is enabled for the signal coming from the vocal

7. Adjust the Threshold for each stage so the vocal peaks trigger a subtle cut. Fig. 3 shows a range of 12 dB, so the cuts shown are around -2 dB to -3 dB. That may not seem like much, but it’s sufficient to open up space for the vocal.

8. Optimize the setting for each Threshold parameter. To compare the processed and unprocessed sound, turn off the Vocal track’s Send. Don’t disable the Sidechain at the Pro EQ3 instead, or the EQ will respond to the mix’s dynamics instead of the vocal’s.

Figure 3: The violet waveform is the Vocal feeding the sidechain. The blue waveform is the stereo mix. The colored curves are the five EQ stages. Set LF and HF to Peaking mode. The wavy white line toward the center shows how much of a cut was occurring when this screen shot was taken.

9. Use the Vocal track’s Send slider to fine-tune the level going to the Pro EQ3’s sidechain.

This technique assumes the vocal has a consistent dynamic range, either from compression or from the techniques in the blog post about why I don’t use compression anymore. Otherwise, loud parts will push the background down further—but a lower level isn’t needed when the vocal is at its loudest. If the vocal’s dynamics are an issue, automate the Vocal track’s Send to reduce the amount of cut for loud vocal sections.

Because there are so many variables, there are many ways to optimize the sound:

- Narrowing the Q may provide much of the benefits of this technique without affecting the submix as much.

- You might not want to set the Range parameter as low as it is in fig. 3, so that there are “guardrails” against the Threshold settings being too low and causing too deep of a cut.

- Broadening the Q makes the effect cover a wider frequency range, so you may not need to cut as much (fig. 4). This is more like the traditional ducking used in voiceovers.

Figure 4: Broader Q settings give less focused cuts.

Remember that this technique’s intention is to add a subtle enhancement—it’s not a cure for a mix, arrangement, or vocal that needs work. However, it can provide that extra little something that makes a vocal stand out a bit more and fit more comfortably into a mix.

Should You Use Highpass Filters when Mixing?

Engineers sometimes advocate using high-pass filters to “clean up the low end and tighten the sound.” Others believe that because of issues inherent in highpass filters, they should be used sparingly, if at all. So, who’s right? Well, as with many aspects of audio technology, they both are in some ways. Let’s dive deeper, and then explore Studio One’s clever highpass filtering solution.

But before getting into the details, let’s look at the big picture. Joe Gilder did a video called THIS is Eating Up All Your Headroom in Your Productions where he shows how low-end energy can accumulate and reduce headroom with no sonic benefits. This is why engineers often apply a highpass filter to a final mix. So, let’s look at the sources that can lead to this accumulation of low-frequency energy, and the right way to fix them within individual tracks before they start accumulating in your final mix.

The Case for Highpass Filtering

Sometimes, low-frequency artifacts that you don’t want travel along with your audio. One potential issue is a directional microphone’s proximity effect, where getting closer to the mic boosts bass unnaturally. Hitting guitar pickups accidentally can generate low-frequency sounds. Transposing samples down by a couple octaves may put energy in the sub-sonic range and even if you can’t hear sub-sonic audio, it uses up headroom.

Highpass filtering has other applications. Too many instruments overlapping in low-frequency ranges can create a muddy sound. For example, you might want to reduce some of a guitar’s low frequencies to avoid interfering with bass. This is usually what people mean by “tightening up” the sound.

The Case Against Highpass Filtering

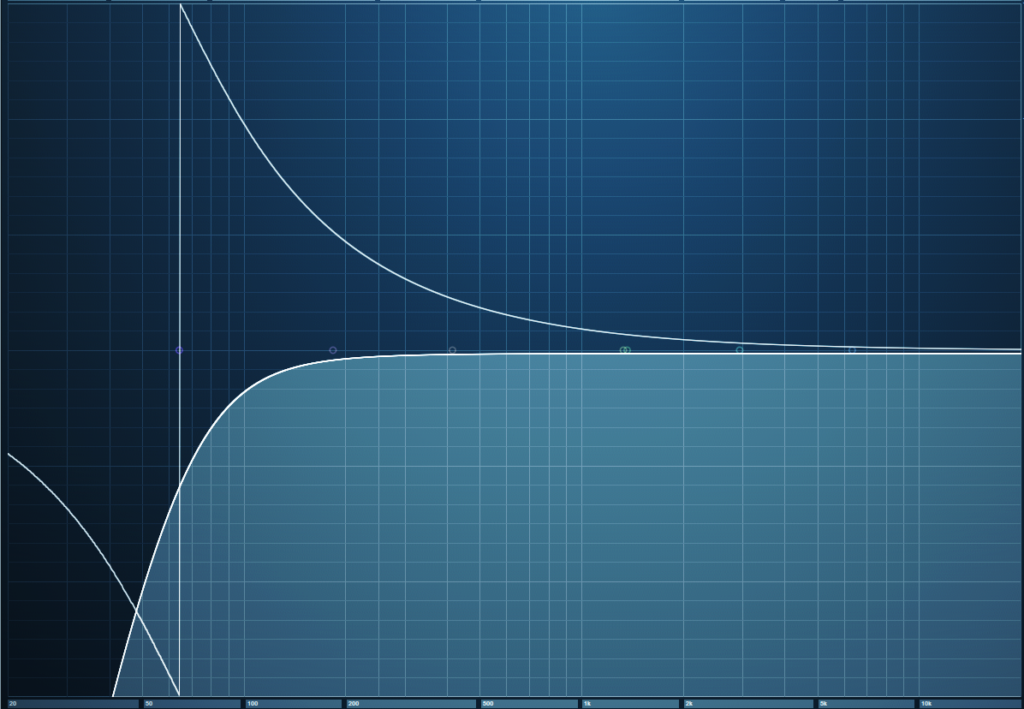

Analog filters produce phase shifts, but the phase shifts in highpass filters with steep slopes are particularly drastic around the cutoff frequency. Most digital filters model analog filters, so they also have phase shifts. Fig. 1 shows a typical example of phase shift in a digital highpass filter with a 100 Hz cutoff and a 24 db/octave slope. The bright line is the filter curve, the darker line shows the amount of phase shift.

Figure 1: Phase shift around the cutoff frequency of a 24 dB/octave highpass filter. The horizontal axis goes from 20 Hz to 20 kHz, so the phase shift impacts the audio well into the midrange. The vertical axis covers -180 degrees to +180 degrees of phase shift.

Wow! That looks scary, doesn’t it? It would look even scarier if the slope was steeper than 24 dB/octave. Fortunately, our hearing can’t detect phase changes—unless the audio interacts with other audio. This is why if you set a phase shifter effect’s dry/wet control to all wet or all dry with no modulation, the sound is the same. You hear the phase-shifted effect only when there’s a mix of wet and dry sounds.

When mixing, this phase shift can matter if two signals with similar waveforms are in parallel. For example, consider bass through a DI in parallel with bass through an amp, or two mics at different distances from an acoustic guitar or group of backup singers. The worst-case scenario is multiple acoustic instruments being recorded simultaneously in an acoustic space—the inevitable leakage means the various tracks will have quite a bit of audio in common.

Differing mic distances from a source will cause phase shifts anyway, but using a typical highpass filter (e.g., to reduce p-pops with vocals) will accentuate the phase shifts. In either case, if the parallel tracks have enough audio in common, when they’re mixed together phase shifts will alter the sound.

Solution #1: Don’t Worry, Be Happy

In many cases, tracks won’t be in parallel with other tracks that have similar or identical audio, so there won’t be any audible degradation from phase changes caused by a highpass filter. If using a highpass filter does introduce phase problems, cutting with a shelf or peak filter instead can reduce the low frequencies (albeit not in the same way). These filter types produce less drastic phase changes.

Solution #2: The Pro EQ3’s LLC Filter

Highpass filters with steep slopes are popular because of their ability to remove bass artifacts and tighten up the sound. But if you need to tighten up or reduce bass artifacts with multiple tracks, inserting all those highpass filters will contribute significant phase changes. Phase variations in the bass range can be a problem (as anyone who’s tried to mix in a small, untreated room knows), so it’s unfortunate that highpass filters are the best choice for solving these problems.

However, linear-phase highpass filters don’t produce phase shifts—that’s their outstanding characteristic. You can use as many linear-phase highpass filters as you want, and not introduce any phase shifts.

But that has its own complications, because linear-phase filters require a lot of processing power. Using several multi-stage, linear-phase EQs in a project can bring your CPU to its knees pretty quickly, as well as introduce an annoying amount of latency.

This is why Studio One’s solution is particularly elegant. The Pro EQ3 has a single linear-phase highpass filter stage (fig. 2). This covers the most common need for a linear-phase filter in most projects, without the CPU burden of a multi-stage linear-phase EQ where you may not need linear-phase operation for the other stages anyway.

Figure 2: The LLC linear-phase highpass filter (outlined in white) is producing the low-frequency cut outlined in light blue.

Enabling the LLC stage contributes about 31 ms of latency compared to the 50-100 ms from a typical multi-stage linear EQ, and takes care of the frequency range where you’re most likely to need a linear-phase EQ. If adding the LLC filter is still too CPU-intensive for a project, or if the latency is bothersome, you can always invoke the “Transform to Rendered Audio” option. Check “Preserve Real Time State” if you think you may need to edit the tracks effects’ settings in the future. This allows you to return to the unrendered audio, make your edits, and then re-render.

The LLC’s natural slope is 24 dB/octave, which will cover most low-frequency problems that need a solution. For general tightening, you may prefer the 12 dB/octave slope obtained by clicking the “Soft” button.

So—Highpass Filtering, Yes or No?

The answer is…both! If you need to highpass an individual track, go ahead and do it if the results sound better—you won’t need to use a linear-phase filter, so there won’t be CPU issues. But if you need to use highpass filtering with parallel tracks that have audio in common, the LLC stage is a clever solution. Furthermore, if you need a slope that’s steeper than 24 dB/octave, supplement the LLC with a shelf filter set for a mild slope. This cuts the low-frequency audio further, but won’t add as substantial a phase shift as a non-linear-phase highpass filter set to a steeper slope.

Why I Don’t Use Compressors Anymore

This wasn’t a conscious decision, or something I planned. But when I looked through my last few songs while seeking candidates for a book’s screenshots, I was shocked to realize there were almost no channel inserts with compressors. Curious, I went back even further, and found that I’ve been weaning myself off compressors for the past several years without even knowing it. WTF? What happened?

First of All, It’s 2023

Compressors are at their very best when solving problems that no longer exist. I certainly don’t need to control the levels of the PA installations at the 1936 Berlin Olympics (one of the first compressor applications). In the pre-digital era, compression kept peaks from overloading tape, and lifted the quiet sections above the background hiss and hum. But it’s 2023. Compression isn’t needed to cover up for vinyl or tape’s flaws. Besides, we have 24-bit A/D converters and increasingly quiet gear. Today’s technology can accommodate dynamic range.

Even though compression does bring up average levels for more punch and sometimes more excitement, to my ears (flame suit on) the tradeoff is that compression sounds ugly. It has artifacts, and adds an unnatural coloration. Furthermore, the way it reduces dynamic range takes away an emotional element we may have forgotten existed—because it’s been clouded by compression for decades. So, how can we retain the benefits of compression, yet avoid the ugly aspects?

Replacing Bass Compression

In my studio musician days, compressing bass was a given (not compressing bass may even have been against Local 802’s by-laws, haha). But I prefer light saturation. It clips off the peaks, gives more sustain because the average level can be higher, and doesn’t produce a “pop” on note attacks. (Yes, lookahead helps with compression pops, but then this neuters the attack.)

Saturation not only allows a higher average level, but adds harmonics that help bass stand out in a track. And bass needs all the help it can get, because low frequencies push speakers and playback systems to the limit. It’s amazing how much saturation you can put on bass, yet when part of a mix, the bass sounds completely clean—and you can hear all the notes distinctly.

Fig. 1 shows settings I’ve used in recent projects. RedLightDist sounds wonderful, while Autofilter (used solely for its State Space saturation) has the advantage of including a lowpass filter. So, you can trim the harmonics’ higher frequencies if needed.

Figure 1: (top) RedLightDist settings for saturation. (bottom) Autofilter taking advantage of State Space distortion.

Replacing Vocal Compression

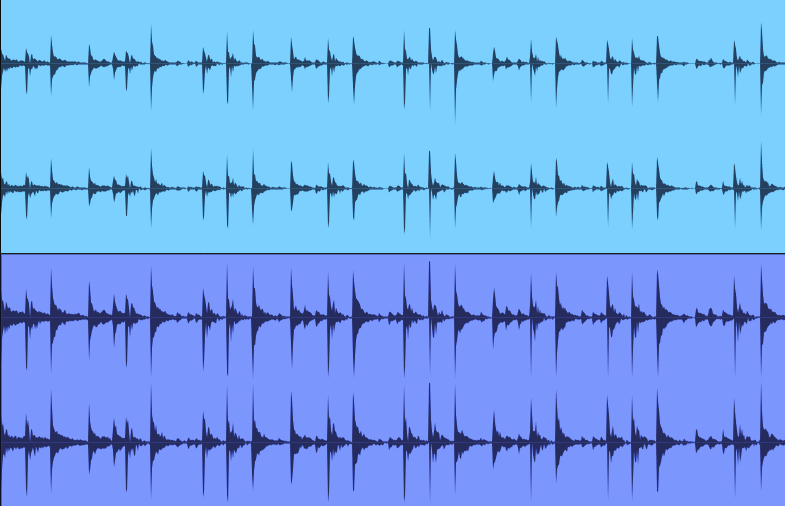

Compression keeps vocals front and center by restricting dynamics, so the soft parts don’t get lost. But there’s a better option. Gain Envelopes and normalization allow tailoring vocal dynamics any way you want—without attack or release times, pumping, breathing, overshoot, or other artifacts. The sound is just as present and capable of being upfront in a mix as if it’s compressed. However, the vocal retains clarity and a natural vibe, because gain envelopes and normalization have no more effect on the sound than changing a channel fader’s level (fig. 2).

Figure 2: A typical vocal, before and after using a Gain Envelope to edit the level for more consistency.

Even better, while you’re editing you can also tweak mouth clicks, pops, and breaths in a way that compressors cannot. I’ve covered using Gain and Event Envelopes before, so for more info, check out the video Get Better Vocals with Gain Envelopes. Also, see the blog post Better Vocals with Phrase-by-Phrase Normalization.

I’m not the world’s greatest vocalist by any means, yet people invariably comment on how much they like my vocals. Perhaps much of that is due to not using compression, so my voice sounds natural and connects more directly with listeners.

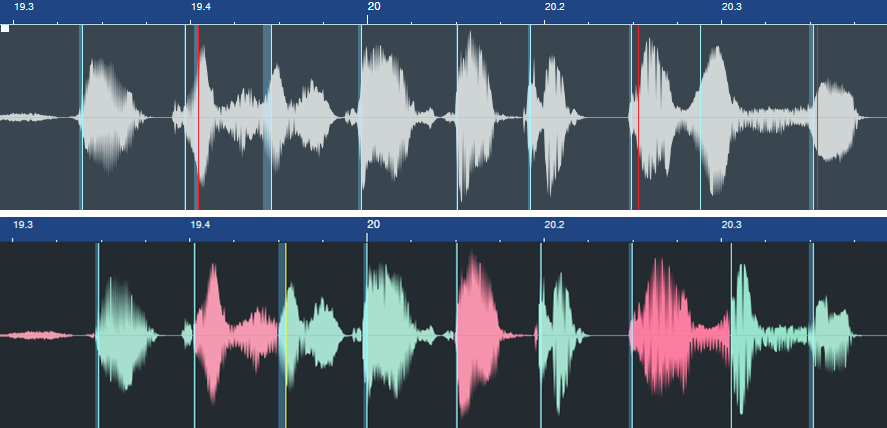

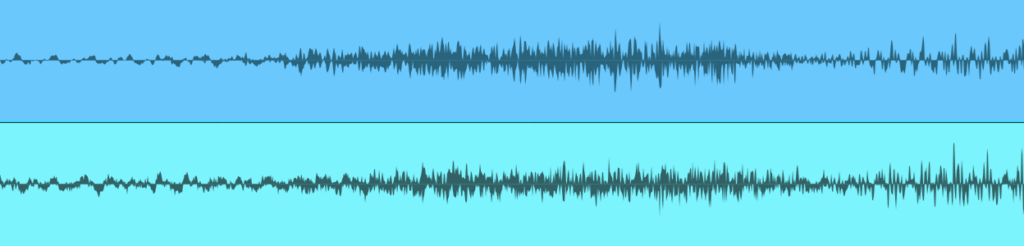

Replacing Drum Compression

Adding compression on drums for more “punch,” as well as to bring up room ambience, is common. However, drums were the first instrument where I ditched compression in favor of limiting. Limiting keeps the peaks under control, but doesn’t change their shape and also allows for a higher average level. This brings up the body and room sound. (Note: Limiter2 is particularly good for this application. You may not have equally good results with other limiters.)

Look at the drum waveforms in fig. 3. Both have been normalized to the same peak levels, but the lower one had 5 dB of limiting. The peaks are still strong, and the average level is higher. Fortunately, this amount of limiting isn’t enough to reduce the drum’s punch. In fact, the punch and power is stronger than what I’ve been able to obtain with compression.

Figure 3: The top drum waveform is prior to limiting. The bottom one has had 5 dB of limiting. Both are normalized to the same peak value.

Final Comments

Although I don’t use compression much anymore for audio, I do use it as a tool. Gobs of compression can increase guitar sustain. Inserting a compressor prior to an envelope filter can restrict the dynamic range for more predictable triggering. Using two compressors in series, set to very low ratios and high thresholds, “glues” tracks and buses together well. Then again, that’s because the effect is so subtle the result doesn’t sound compressed.

But let’s get one thing straight: I certainly don’t mean this as a diss to those who like the sound of compression. It has its own sound, and it’s become a fixture in pop and rock music for a reason. Top engineers who line their walls with gold records have gotten a lot of mileage out of compression. I would never recommend that people not use compression. What I do recommend is trying other options. To hear what these techniques sound like, check out any recent music on my YouTube channel.

I’m sure my avoidance of compression is a personal bias. I’ve worked on many classical music sessions, and my gold standard for sound is live acoustic music. Neither one has anything to do with compression. So, it’s probably not surprising that even in rock and EDM productions, I strive for clarity and a natural, lifelike sound. Compression just doesn’t do that for me. But hey, it’s 2023! Now we have tools that can give us the goodness of compression, without the drawbacks.

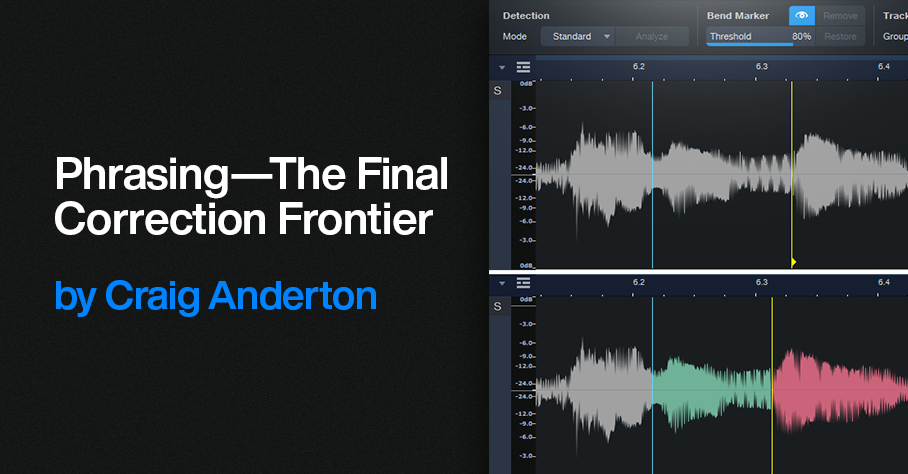

Phrasing—The Final Correction Frontier

First, a follow-up: In the October 13 tip about creating Track Presets for parallel processing, I mentioned that Track Presets can’t include buses, which is wrong. Sorry! However, the premise behind the tip is still valid. For example, by using tracks (which can record) instead of buses (which can’t), you can create Track Presets for recording tracks with effects that produce random changes in real time. Or, create Track Presets optimized to record hands-on effects control while recording the results. Another part of the tip about creating a dummy bus so that a channel fader can provide a master “send” to tracks, without sending audio to the main bus, can also be useful. Now, on to this week’s tip.

We have tools to correct pitch, and tools to correct timing. But one of the most important aspects of expressive music is phrasing, especially with vocals. Pushing a vocal slightly ahead of the beat, or lingering on a phrase a bit longer, can enhance the vocal performance.

Fortunately, the Bend Tool can alter phrasing. Of course, vocals don’t have the fast, strong transients to which bend markers usually lock. But we can place bend markers where we want them, and ignore the rhythmic grid. Think of bend markers not only as tools to correct timing, but as tools to add expressiveness to vocals by altering their phrasing.

Getting Started

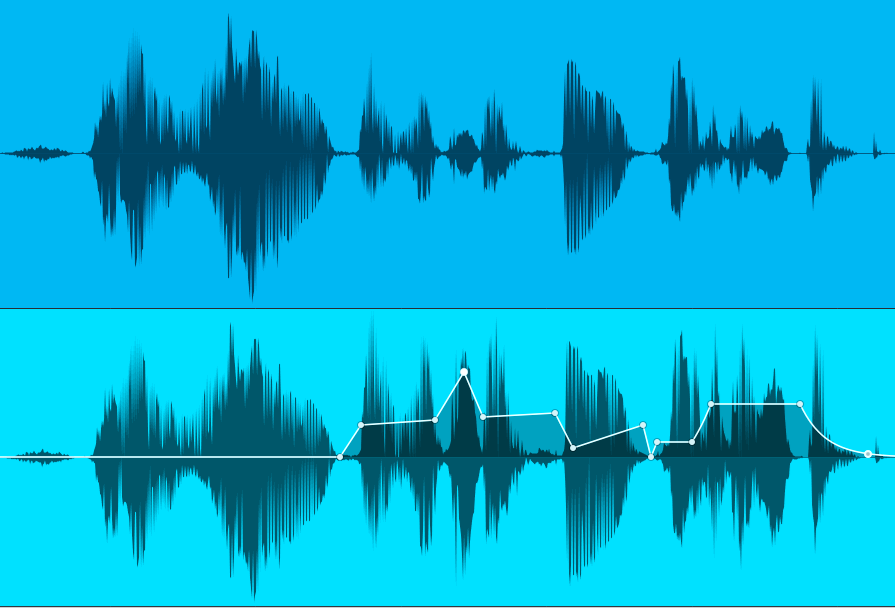

Figure 1: Note the show/hide “eye” button toward the top. Moving a bend marker affects the audio between it and both the previous and next bend markers.

- Turn on Show Bend Markers (the eye button in fig. 1).

- Turn off snap. Phrasing rarely benefits from the grid.

- Remember that stretching involves the interaction of three bend markers. The top part of fig. 1 shows a phrase before moving the yellow bend marker. The lower part shows what happens after moving the bend marker forward in time. Audio between the bend marker and the previous bend marker becomes time-compressed (green coloration). Audio between the bend marker and the next bend marker becomes time-expanded (red coloration).

- You’ll often need to place bend markers manually, in the spaces between words or phrases.

Remove Unneeded Transients, then Edit the Phrasing

Because vocal phrases don’t have defined transients, asking Studio One to detect transients won’t give the same results as percussive instruments. Often, transient pairs will be close together. You want only one of these (usually the one closest to the note beginning). Hover over the unneeded bend markers with the Bend Tool, and double-click to delete them (fig. 2).

Figure 2: In the top image, the bend markers to be eliminated are colored red. The lower image shows the result of altering the phrasing.

In this case, I wanted to tighten the timing and move some notes closer to the beat. But also look at the second bend marker from the right in fig. 2. This had nothing to do with timing, but altered a word’s phrasing to slow down the audio leading up to it, and speed up the audio after it. This led the note more dramatically into the final note.

Here’s another before and after example. The words toward the end have had their phrasings adjusted considerably.

Figure 3: The phrasing slows down toward the end to give the lyrics more emphasis. The bend marker at the far right was added to keep the final word’s length closer to its original length.

Remember that moving a bend marker affects audio before and after the marker. In the bottom of fig. 3, the added bend marker at the end of the last word prevented the audio from being too compressed. Otherwise, the word would have been shortened. In cases where you need to move an entire word earlier or later on the timeline, sometimes it’s easier to split at the beginning and end of the word, and move the Event itself rather than use bend markers.

Custom Markers

If the transient detection isn’t useful with vocal phrasing, you’re better off placing bend markers manually. The Bend Tool options are:

- Click to create a bend marker.

- To alter the phrasing, hover on a bend marker. Then, click and drag to move the bend marker earlier or later on the timeline.

- To move a bend marker without affecting the audio, hold the Alt/Opt key, hover over the marker until left- and right-facing arrows appear, then click and drag.

- Double-click on a bend marker to delete it.