Category Archives: Friday Tip of the Week

Sound Design for the Rest of Us

Last May, I did a de-stresser FX Chain, and several people commented that they wanted more sound design-oriented tips. Well, I aim to please! So let’s get artfully weird with Studio One

Perhaps you think sound design is just about movies—but it’s not. Those of you who’ve seen my mixing seminars may remember the “giant thud” sound on the downbeat of significant song sections. Or maybe you’ve noticed how DJs use samples to embellish transitions, and change a crowd’s mood. Bottom line: sound is effective, and unexpected sounds can enhance almost any production

It all starts with an initial sound source, which you can then modify with filtering, delay, reverb, level changes, transposition, Chord Track changes, etc. Of course, you can use Mai Tai to create sounds, but let’s look at how to generate truly unique sounds—by tricking effects into doing things they’re not supposed to do

Sound Design Setup

The “problem” with using the stock Studio One effects for sound design is…well, they’re too well-designed. The interesting artifacts they generate are so low in level that most of the time, we don’t even know they exist. The solution is to insert them in a channel, amplify the sound source with one or two Mixtools set to maximum gain, and then enable the Channel’s Monitor button so you can hear the weirdo artifacts they generate. Automating the effects’ parameters takes this even further.

However, now we need to record the sounds. We can’t do this in the normal way, because there’s no actual track input. So, referring to fig. 1, insert another track (we’ll call it the Record Trk), and assign its input to the Effects track’s output. Both tracks need to be the same format – either both stereo, or both mono. (Note that you can also use the Record track’s Gain Input Control to increase the effect’s level.) Start recording, and now your deliciously strange effects will be recorded in the new track.

The FX channel is optional, but it’s helpful because the Effects track fader needs to turned way up. With it assigned to the Main bus, we’ll hear it along with the track we’re recording. That’s not a problem when recording, but on playback, you’ll hear what you recorded and the Effects track. So, assign the Effects output to a dummy FX bus, turn its fader down, and now you’ll hear only the Recorded track on playback. The Record Trk will still work normally when recording the sound effects.

After recording the sounds, normalize the audio if needed. Finally, add envelopes, transpose the Event (this can be lots of tun), and transform the effect’s sound into something it was never intended to do. Percussion sounds are a no-brainer, as are long transitions from one part of a song to the next. And of course, the Event can follow the Chord Track (use Universal mode).

The Rotor is a fun place to start. Insert it in the Effect track, and run through the various presets. Some DJs would just love to have a collection of these kinds of samples to load into Maschine. Here’s an audio example.

Audio Example 1 Rotor+Reverb

The next example is based the Flanger.

Audio Example 2 Flanger

Now we’ll have the previous Flanger example follow a strange Chord Track progression, in Universal mode.

Audio Example 3 Flanger+Chord track

Other Effects

This is just the start…check out what happens when you automate the Stages parameter in the Phaser.

Audio Example 4 Phaser Loop

Or turn the Mixverb Size, Width, and Mix to 100%, then vary damping. The Flanger is pretty good at generating strange sounds, but like some of these, you’ll have the best results if you set the track mode to mono. OpenAIR is fun, too— when you want a pretty cool rocket engine, load the Air Pressure preset (under Post), set Mix to 100% wet, add some lowpass filtering…and blast off!

Metal Guitar Attack!

They’re called “power chords” for a reason—that delightful mix of definition, sludge, and hugeness is hard to resist. But can we make them more huge and more powerful? Of course, we can, so let’s get started

This tip gives two options: non-real-time, and real time (using the High Density Ampire pack, although other amp sims and processors can work, too). Either technique also works well for LCR mixing fans.

Non-Real-Time Hugeness

- Insert Ampire in your guitar track, and edit it for your ideal sound (the Default Ampire preset is a good place to start).

- Right-click in the track’s column, and select Duplicate Track (Complete).

- Repeat Step 2. Now you have three identical tracks with identical processing.

- The key to getting Total Hugeness is transposition. Click on one track’s Event, open the Inspector (F4), and set Transpose to -12 (fig. 1). Click on another track’s event, and in its Inspector, set Transpose to +12. Don’t change the pitch of the remaining track.

After the next section, we’ll get into panning and EQ.

Figure 1: The guitar power chord track has been duplicated twice. The audio on the track to the right has been dropped an octave.

Real-Time Hugeness

Follow the steps above for non-real-time hugeness, but don’t do Step 4. Instead:

- For one of the tracks, open up Ampire. Insert the Pitch Shifter before the amp, choose “dn 1 Oct” (fig. 2), click on the top of the pedal, and then drag up until the pedal’s Tune tooltip shows 100. The audio will now be transposed an octave down. If you don’t have the Ampire High Density pack, the transposers in other amp sims will work, but the one in High Density seems better than average.

- Similarly, do the same processing on another track, but this time choose “up 1 Oct.”

What’s Next

Whether you chose real-time or non-real-time hugeness, you now have three tracks: Standard pitch, tuned down an octave, and tuned up an octave. Let’s do panning and levels. Here are some options.

- Standard pitch full left, +12 center, -12 full right. This gives the biggest sound and is used in the audio example.

- Standard pitch full left, -12 full right, and mute the +12 track. This is ideal for all you LCR fans. It opens up a big hole in the center for bass, kick, snare, and vocals.

- Standard pitch full left, +12 full right, -12 full right. Another LCR favorite. The +12 gives a more defined sense of pitch in the right channel, so something else with a strong sense of pitch (e.g., Organ of Doom) can fit comfortably in the left channel.

- Standard pitch center, +12 full left, -12 full right. This emphasizes the main guitar track with the standard tuning.

This approach also lends itself well to automating mute on the various channels. Unmute the octave below when you want to fatten the sound, unmute the octave higher when you want a more defined sense of pitch.

Applying EQ to the transposed audio can customize the sound further. If you’re doing a duo with only drums and guitar, on the octave below track, boost the bass and trim the highs. Pan it to center, and pan the other two tracks left and right. Another possibility is giving more definition to the octave higher track by rolling off the lows and highs a bit and boosting the mids around 2 kHz or so.

Let’s check out the audio example…remember, it’s only one guitar.

Mid-Side Processing with Artist

This is a companion piece to last week’s tip, which described how to implement Splitter functionality in Studio One’s Artist version. The Pro version has a Splitter-based, mid-side processing FX Chain that makes it possible to drop effects for the mid and side audio right into the FX chain. However, the Splitter isn’t what does the heavy lifting for mid-side processing—it’s the Mixtool, which is included with Artist.

Mid-Side Refresher

The input to a mid-side processing system starts with stereo, but the left and right channels then go to an encoder. This sends a signal’s mid (what the left and right channels have in common) to the left channel, while the sides (what the left and right channels don’t have in common) go to the right channel.

The mid is simply both channels of a stereo track panned to center. So, the mid also includes what’s in the right and left sides, but the sides are at a somewhat lower level. This is because anything the left and right channels have in common will be a few dB louder when panned to center.

The sides also pan both channels of a stereo track to center, but one of the channels is out of phase. Therefore, whatever the two channels have in common cancels out. (This is the basis of most vocal remover software and hardware. Because vocals are usually mixed to center, cancelling out the center makes the vocal disappear.)

Separating the mid and side components lets you process them separately. This can be as simple as changing the level of one of them to alter the balance between the mid and sides, or as complex as adding signal processors (like reverb to the sides, and equalization to the mid).

After processing, the mid and sides then go to a decoder. This converts the audio back to conventional stereo.

lMid-Side Channel and Bus Layout

Fig. 1 shows what we need in Artist: the original audio track, a bus for the mid audio, a bus for the side audio, and a bus for the final, decoded audio.

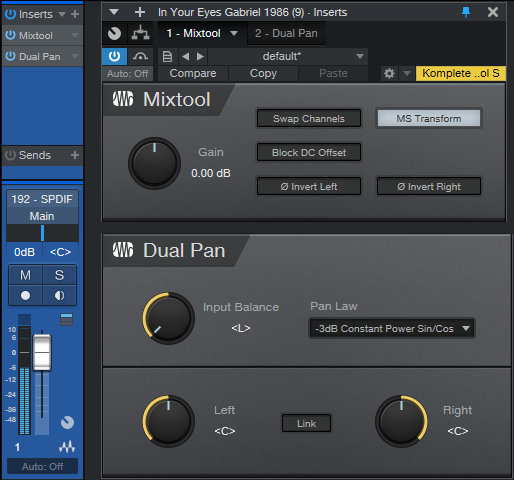

Insert a Mixtool in the original audio track, and enable MS Transform (see fig. 2). Then, we need to send the encoded signal to the buses. Insert one pre-fader send, assign it to the Mid bus, and pan it full left. Then, insert another pre-fader send, assign it to the Sides bus, and pan it full right.

Figure 2: The Mixtool settings are the same for both Mixtools. The middle Dual Pan inserts in the Mid bus, while the lower Dual Pan inserts in the Sides bus.

Referring to fig. 2, the Mid bus has a Dual Pan inserted after any processing, with both controls panned full left. Similarly, the Sides bus has a Dual Pan inserted after any processing, with both controls panned full right. (The Pro EQ2 and OpenAIR inserted in fig. 1 are included just to show that you insert any effects before the Dual Pan plug-ins; they’re not needed for mid-side processing.) Pan the Mid bus pan fader left, and the Sides bus pan fader right.

Assign the bus outputs to the Decoded bus. This has a Mixtool inserted, again with MS Transform enabled. And that’s all there is to it—the Decoded bus is the same as the original audio track, but with the addition of any changes you added to the Mid or Side buses.

To make sure everything is set up correctly, remove any effects from the Mid and Sides, and set all the bus levels to 0. Copy the original audio track, insert a Mixtool into it, and enable Invert Left and Invert Right. Adjust the copied track’s level, and if there’s a setting where it cancels out the decoded track, all your routing, panning, and busing is set up correctly. Happy processing!

Make a Splitter for Studio One Artist

One of my favorite Studio One Professional features is the Splitter, and quite a few of my FX Chains use it. If you own Studio One Artist, which doesn’t have a Splitter, you may look longingly at these FX Chains and think “If only I could do that…”

Well, you can implement most splitter functions in Studio One Artist, by using buses. All the following split options are based on having a track that provides the audio to be split, along with pre-fader sends to additional buses. Note that the track’s fader should be turned all the way down.

Normal Split

The Splitter’s Normal mode sends the input to two parallel paths, which is ideal for parallel processing. For Artist, we’ll duplicate this mode with two buses, called Split 1 and Split 2 (fig. 1).

Figure 1: How to create a Normal split in Artist.

The sends to the buses are pre-fader, and panned to center. One send goes to Split 1, and the other to Split 2. Now you can insert different effects in Splits 1 and 2 to do parallel processing.

Channel Split

The Channel Split mode also splits the input into two parallel paths. One path is for the left channel, while the other path is for the right channel.

Figure 2: How to create a Channel Split in Artist.

The setup is the same as for the Normal Split (fig. 2), except that each bus has a Dual Pan inserted. The Dual Pan for the left channel has the Input Balance set to <L>, while the Dual Pan for the right channel has the Input Balance set to < R>. I recommend the -6dB Linear Pan law so that if you pan either of the buses, the level remains constant as you pan from left to right.

Frequency Split

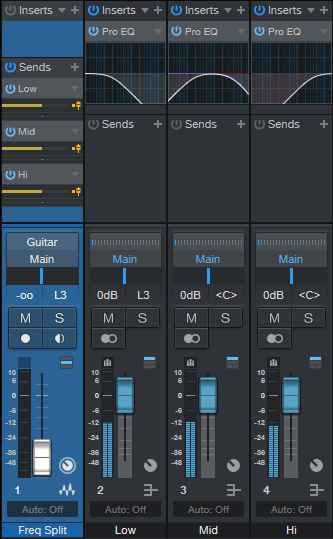

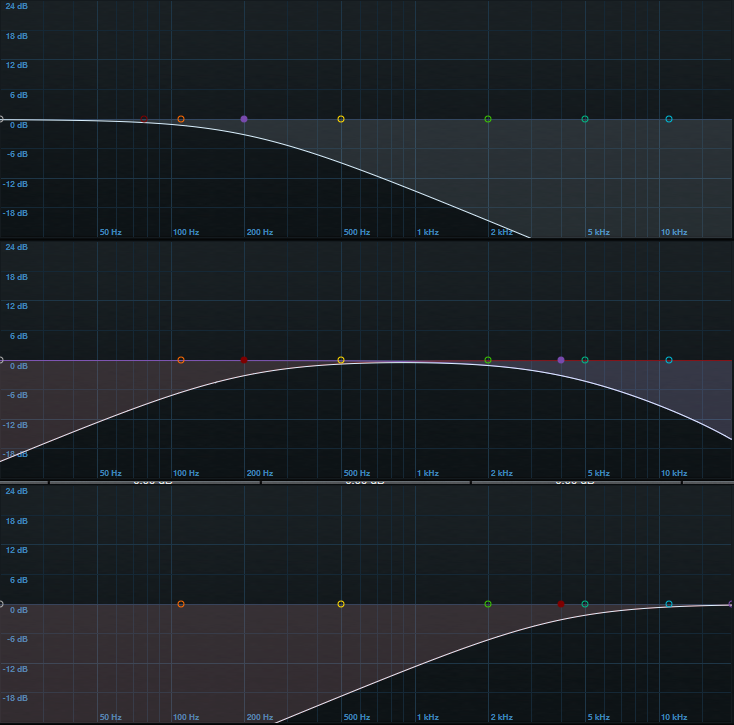

This is tough to duplicate, because the Splitter can split incoming audio into five frequency bands. If other DAWs don’t do it, we can’t expect Artist to do it. But, we can do a three-way, tri-amped split into low, mid, and high frequencies (fig. 3).

Figure 3: Tri-Amp Frequency Split.

This split is like the Normal Split, except that there are three buses and pre-fader sends instead of two, and each bus has a Pro EQ2 inserted. Each EQ covers its own part of the frequency spectrum—low, mid, and high (fig. 4). Using 6 dB/octave slopes doesn’t provide as much separation between frequency ranges as steeper slopes, but the gentler slopes are necessary to make sure the frequency response is flat when you mix the three channels together.

Figure 4: (Top to bottom) low, mid, and high curves.

The only filter sections we need to use are High Cut and Low Cut—you can ignore everything else. Fig. 5 shows the settings. All bands have 6 dB/octave slopes.

Enable the Low band’s Pro EQ2 HC (High Cut) filter, and choose 200 Hz for frequency. Enable the Mid band’s Pro EQ2 LC (Low Cut) filter, and set it to 200 Hz; also enable the HC filter, and set it to 4.00 kHz. Finally, enable the High band’s Pro EQ2 LC filter, and set it to 4.00 kHz. These frequencies are a good starting point, but you may want to modify the split frequencies for different types of audio sources. Just make sure that the low band HC frequency is the same as the mid band’s LC frequency, and the Mid band’s HC frequency is the same as Hi band’s LC frequency.

Figure 5: Filter control settings.

Granted, setting up these splits takes more effort than dragging a Splitter plug-in into a channel, but the result is the same: cool parallel processing options.

The Dynamic Brightener—Reloaded

In April 2019, I did a Friday Tip called The Dynamic Brightener for Guitar. It’s kind of a cross between dynamic EQ and a transient shaper, and has been a useful FX Chain for me. In fact, it’s been so useful that I’ve used it a lot—and in the process, wanted to enhance it further. This “reloaded” version makes it suitable for more types of audio sources (try it with drums, bass, ukulele, piano, or anything percussive), as well as less critical to adjust. It also lessens potential high-frequency “smearing” issues—the original version applied large amounts of boost and cut, with a non-linear-phase EQ.

Although the original version could have been built using a Splitter, I did a bus-based implementation so that it would work with Studio One Artist. This new version needs to use the Splitter (sorry, Artist users), but that’s what allows for the improvements.

Another interesting aspect is that by using the effects’ expanded view in the channel inserts, you don’t even need to open the effect or Splitter interfaces, to do all the necessary tweaking. This makes the reloaded version much easier to edit for different types of tracks.

How It Works

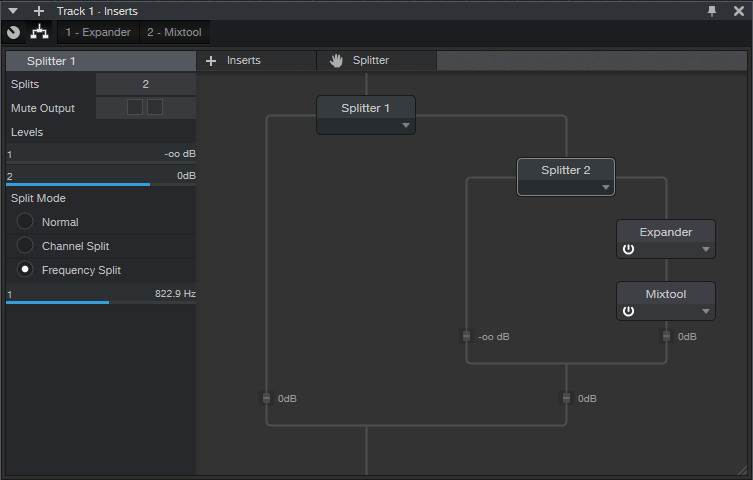

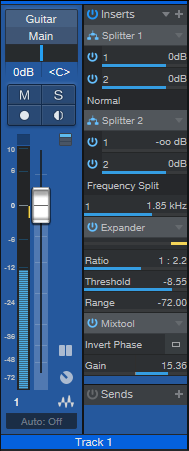

Fig. 1 shows the FX Chain’s block diagram.

Splitter 1 is a normal split. The left split provides the track’s dry sound, while the right split goes to Splitter 2, which is set up as a Frequency Split. The Frequency Split determines the cutoff for the high frequencies going into the right split. Splitter 2’s left split, which contains only the split’s lower frequencies, is attenuated completely. Basically, Splitter 2 exists solely to isolate the audio source’s very highest frequencies.

These high frequencies go to an Expander, which emphasizes the peaks. This is what gives both the transient shaping and dynamic EQ-type effects. Because the high frequencies aren’t very loud, the Mixtool allows boosting them to hit the desired level.

Fig. 2 shows the initial Expander and Mixtool settings. But, you won’t be opening the interfaces very much, if at all…you don’t even need Macro Controls.

Using the Reloaded Dynamic Brightener

In the short console view, open up the “sidecar” that shows the effects. Expand the effects, and set the mixer channel high enough to see the ones shown in fig. 3.

Here’s how to optimize the settings for your particular application:

- Turn off Splitter 1’s output 1 power button. This mutes the dry signal, so we can concentrate on the brightener’s settings.

- Adjust Splitter 2’s Frequency Split to isolate the optimum high-frequency range for brightening. This can be as low as 1 kHz or less for guitars with humbucker pickups, on up to 6 kHz (or more) to emphasize drum transients.

- Set the Expander’s Ratio and Threshold parameters for the desired amount of brightening and transient shaping. Higher Threshold settings pick off only the top of the boosted high-frequency peaks; the Ratio parameter controls the transient shape. The higher the ratio, the “peakier” the transient.

- After editing the high frequencies, re-enable the dry signal by turning on Splitter 1’s output 1 button.

- Mix in the desired amount of brightening with the Mixtool Gain parameter. In extreme cases you may want to increase the level control at the end of the Splitter 2 branch, or the output level from Splitter 2 output 2, but this will be needed rarely, if at all.

- As a reality check to determine what the brightener contributes to the sound, turn off either Splitter 1 or Splitter 2’s output 2 power button to mute the brightened signal path.

This is a tidier, easier-to-adjust, and better-sounding setup than the original dynamic brightener. Download the FX Chain here—the default settings are for dry guitar, and assume a normalized overall track level. With lower track levels, you’ll need to lower the Expander Threshold, or boost output 2 from Splitter 1. But feel free to tweak away, and make the Reloaded Dynamic Brightener do your bidding, for a wide variety of different audio signals.

The Virtual “Back of the Tape Box.”

In the 20th century, tape reels came in boxes. Engineers wrote information about tracks, running order, timing, credits, and such on the back of the box. And because it was a box, you could fold up some sheets of paper and include lyrics, notes, and other information

These days, when you open a project, it’s just like you left it. But what mics did you use? How was the tone control set on the bass? And you got those loops from…which sample library? If you ever need to re-visit a track, fix a glitch, do an overdub, or weeks pass before you can finish a project, you’ll need to know these details. Let’s talk about taking notes, and while we’re keeping track of things, let’s also create a lyrics track.

Taking Notes

To access Studio One’s virtual “back of the tape box,” choose Song > Song Information.

- The Info tab shows selected meta data, info from the Song Notes tab, and any image you uploaded to Song Setup. The image can show an album cover, but also a miking setup, an analog processor’s control settings, or a cool picture that inspires you.

- For developing song lyrics, I keep the Song Notes tab open, and do my writing/editing there. Saving lyrics with a song is convenient. However, it’s also useful for other notes—session personnel, web site URLs with reference info, and so on.

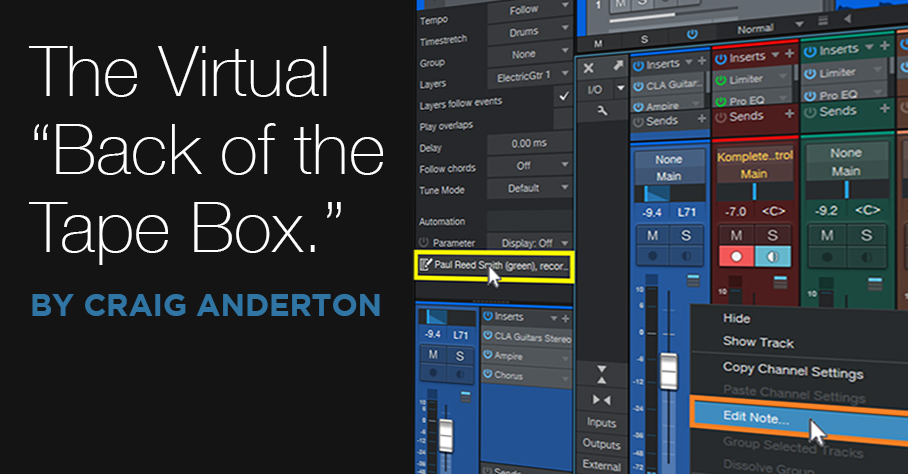

- Track Notes (fig. 1) is where you can include all track-related information. It’s ideal for info that’s not included in a preset, like the vocal mic of choice, analog processor control settings, and which pickup you used on a guitar.

Track Notes Access Shortcuts

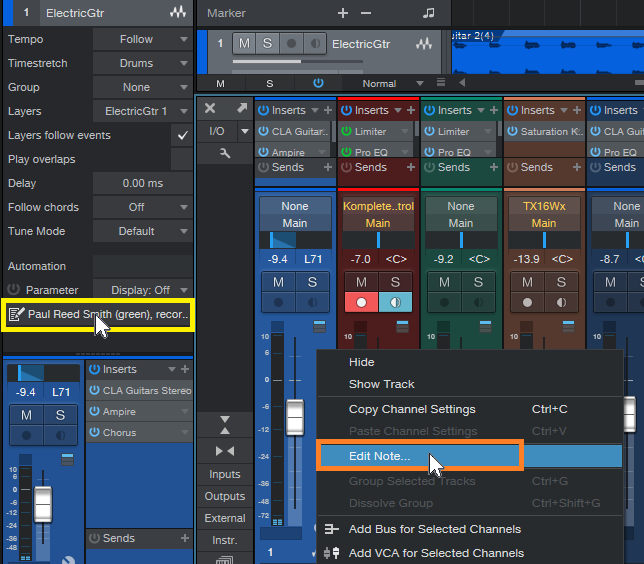

In addition to accessing track notes in the Song Information menu, you can scroll down in the Inspector to the field below automation, and click on it to open the corresponding Track Notes (fig. 2). Or, right-click anywhere within a Console channel, and select Edit Note from the context menu. This is the fastest way to view or edit Track Notes, compared to going to Song Information, selecting a tab, and then clicking on the track label.

Figure 2: Open track notes from within the Inspector by clicking, or in a mixer Channel by right-clicking.

Furthermore, you can supplement Track Notes by entering information in the track name itself. Hovering over the name in the Arrange window or a mixer Channel (fig. 3) shows whatever you entered, which can be quite long if needed. This is useful for temporary notes, like if you recorded several similar parts, and need to differentiate among them.

Pipeline Docs

Analog processors…you love ‘em, right? But when they don’t have presets, and you’re using them with Pipeline, you’ll want to know how the controls were set. Pipeline’s image icon (lower left) allows uploading an image of control settings, while the pencil icon allows adding a note (fig. 4).

Figure 4: The rack of effects from my book “Electronic Projects for Musicians,” being used with Pipeline.

A photo larger than 1200 x 1200 will be scaled to fit the image space, but click on the image, and it expands to the original size. You may even be able to see all the controls on a rack-mount piece of gear.

If you have an analog synthesizer with so many controls they won’t fit in a picture, no problem. Pipeline doesn’t have to be used for its intended purpose. You can take a picture of the synth’s oscillators, another of the filters, another of the envelopes, Then, stack multiple Pipelines within a track, to be used solely as a picture gallery. However, each instance does add latency—when you don’t need to see the pictures, disable the track, and hide it to reduce clutter.

Of course, you could always put the images in a folder, and include that folder in your song folder. But it’s kinda cool that everything you need to know about a song can be stored within that song.

The Lyrics Track

A lyrics track is helpful, because you always know where you are in the song—not just in the “chorus” or “verse.” It can be located right above a vocal, so it’s easy to find and select a particular part that needs editing, overdubbing, deleting, etc. Although Studio One doesn’t have a lyric track per se, you can put one together in two ways (fig. 5). There are pros and cons to each approach.

Marker-based lyric track. Lyric markers are quite readable, and have useful songwriting functions:

- Select the Marker track, open the Inspector, and jump to a particular phrase by clicking on it. It’s a quick way to get where you want to go.

- Right-click on any marker, select “Create Arranger Sections from Markers,” and now you have the start of an Arranger Track based on the lyrics.

- Right-click on a marker, and choose “Stop at Marker” to make sure that playback won’t continue past that point.

Event-based lyric track. This might be best if you already have a lot of markers inserted, and don’t want to add more. Create a dummy track, and populate it with events whose lengths correspond to phrases. One advantage is that you can color-code the events to help guide you through a vocal by emphasizing certain phrases. Another advantage is that if you zoom in or out, the Event will continue to span the length of the chosen phrase. A Marker is always anchored to the beginning.

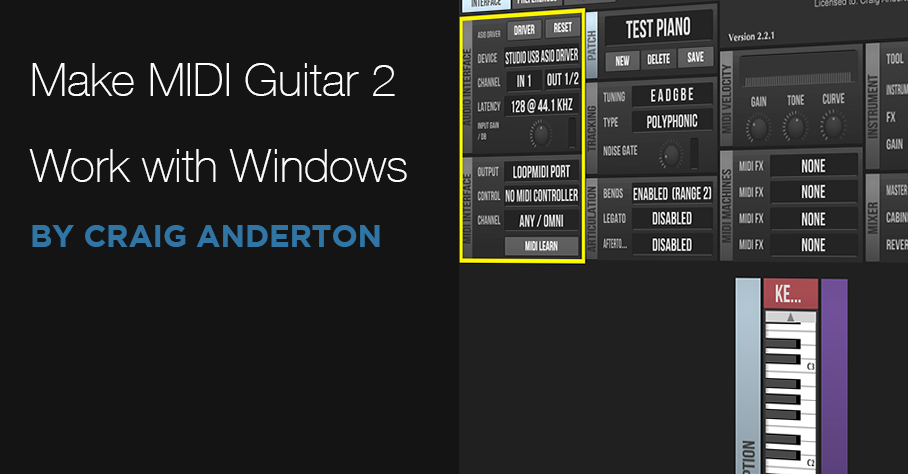

Make MIDI Guitar 2 Work with Windows

Jam Origin’s MIDI Guitar 2 (MG2) is a software-only, guitar-to-MIDI converter. It doesn’t require any special jacks, pickups, or multipin connectors—just give it your guitar’s audio output. MG2 works stand-alone, but can also insert as a plug-in into your guitar’s audio track, and generate a MIDI output. This shows up as an available MIDI input to an instrument track.

Unfortunately, when used as a plug-in, I encountered numerous issues—primarily degraded pitch bend performance and problems with VST3 instruments (apparently this is a common issue). I just couldn’t get it to work in a satisfying way.

However, there’s a workaround—and it works well. Pitch bends translate more smoothly, and it doesn’t matter whether the virtual instrument you’re driving is VST2 or VST3. Of course, like any MIDI guitar, you’ll need to clean up the data a bit but mostly, this involves just deleting notes shorter than a certain length. Pitch bending often needs editing, but on the other hand, MG2 handles vibrato very well.

The Solution: Virtual MIDI Ports

The solution is not to use MG2 as a plug-in. Instead, run it in stand-alone mode, assign its output to a virtual MIDI port, and set Studio One’s virtual instrument to that same virtual MIDI port. This approach bypasses any potential issues caused by taking MIDI data from an audio plug-in out, passing it through a DAW, and feeding it into an instrument.

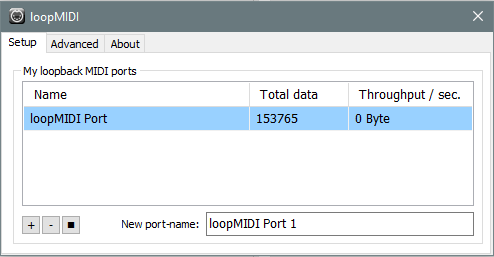

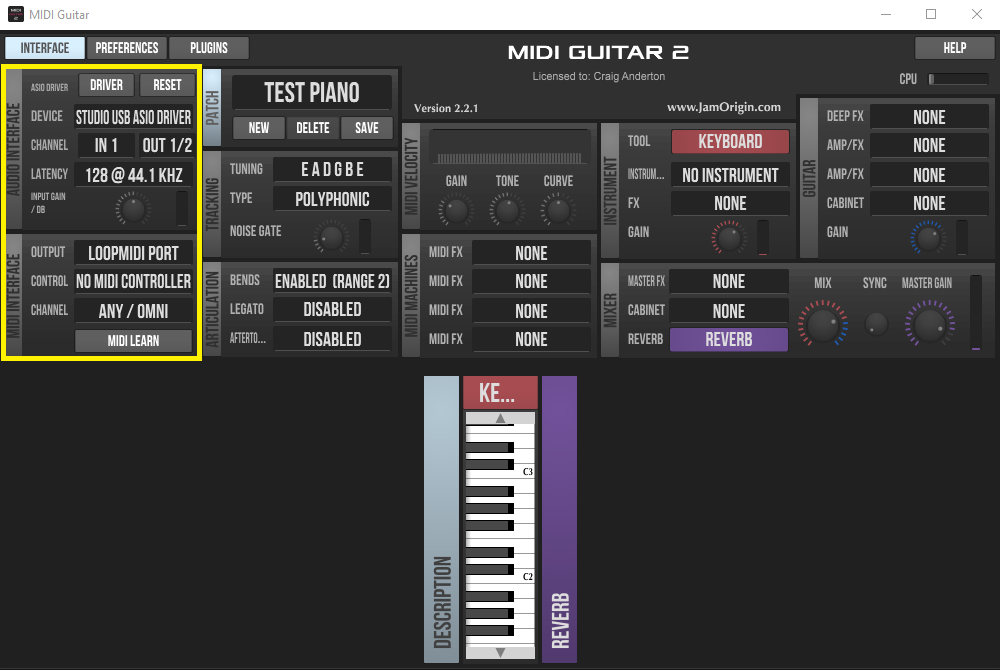

Unlike the Mac, Windows doesn’t support virtual MIDI ports natively. However, the loopMIDI accessory program from Tobias Erichsen solves that. Download the program, and install it. The loopMIDI icon shows up in the taskbar. Right-click on it, and choose Configure loopMIDI (also check Autostart loopMIDI while you’re at it). Configuring just means hitting the + sign to create a port (fig. 1).

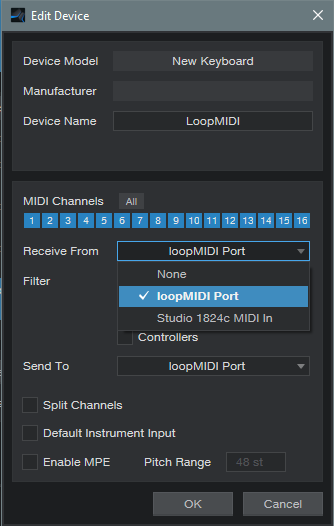

After installing loopMIDI, we need to tell Studio One there’s a new MIDI control device. Open Studio One (because you checked Autostart, loopMIDI will already be running), and choose Studio One > Options > External Devices. Click the Add button, and set up loopMIDI as a MIDI keyboard (fig. 2).

Next, set up MG2 in stand-alone mode (fig. 3). Note that there’s no problem with running MG2 and Studio One at the same time using a PreSonus ASIO interface (probably others as well).

In the Audio Interface section, specify the interface driver, and the input where MG2 will expect to find your guitar’s audio. Jam Origin recommends using 44.1 kHz with 128 samples of latency, and I didn’t argue. Set MG2’s MIDI Interface output to the loopMIDI port. This is where MG2 will send the MIDI data derived from your guitar.

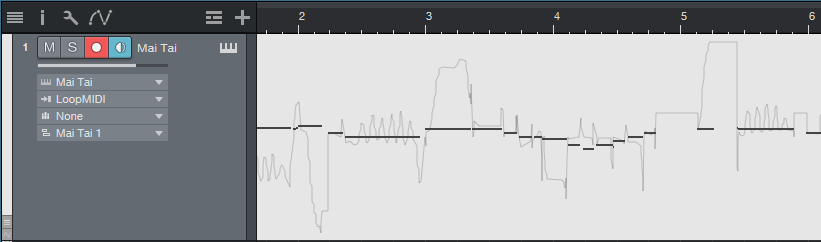

For the final step, insert your virtual instrument into Studio One, and set its input to loopMIDI (fig. 4). Note that you don’t need to insert a guitar track, unless you want to record your guitar part as well as drive a virtual instrument. I insert a guitar track anyway, if for no other reason than to be able to use Studio One’s tuner—pitch-based guitar-to-MIDI converters seem to like accurate tuning.

Figure 4: The Mai Tai input is set to loopMIDI. Note data (in monophonic mode), along with pitch bend, has been recorded.

Optimizing MIDI Guitar 2

To recap, your guitar goes into an audio interface input, MG2 in stand-alone mode listens to the audio input and converts it to MIDI, and then the MIDI data goes to your virtual instrument. However, we’re not quite done, because MG2 has various customization options.

The stand-alone version can play instruments, but we don’t need to do that because we’re triggering instruments in Studio One. So for the Instrument, choose No Instrument.

There’s a choice of polyphonic or monophonic tracking, depending on whether you want to play chords or single-note lines, and set bend to the same range in semitones as your instrument.

Experiment with Legato, which can even give infinite sustain. Gain and Curve help tailor your playing for the best triggering. In my experience, MG2 seems happiest when you don’t hit the strings too hard. In any event, those are the basics. Sorting out MG2’s settings in detail isn’t necessary, because you can go to the Jam Origin website and delve into the documentation there.

I must say that when I first tried using Jam Origin, I was frustrated, and felt I had just wasted $99. But after using the standalone/virtual port workaround, now I’m a happy camper. Sure, MIDI guitar isn’t perfect. But MG2 can lay down some tasty MIDI lines, and as to sawtooth-based power chords… well, let’s just say they sure are fun.

The Flanger Lab

The Flanger Lab FX Chain provides a wide variety of effects, from traditional flanging to psycho-acoustic panning, and can even incorporate some mid-side mojo—it all depends on how you set the controls. Originally, I had planned to include a control panel for Studio One Pro users, but there are simply too many options to fit into eight controls. It’s more fun just to open up all the effects, play with the knobs, and be pleasantly surprised.

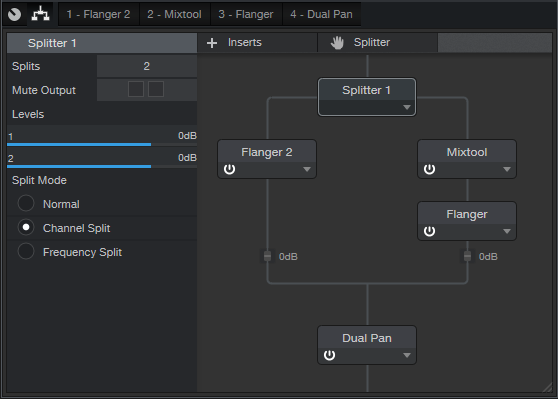

The FX Chain itself is fairly straightforward (fig. 1): A split into two Flangers, one preceded by a Mixtool to invert the phase, and a Dual Pan at the end.

Now let’s look at the effects (fig. 2).

The audio example, with stereo program material, uses the settings shown in figures 1 and 2. However, this is just one possible sound. Flanger Lab is equally effective with mono distorted guitar, stereo string pads, and more.

Here are some tips on how different control settings affect the sound.

- Flanger Lab works with mono or stereo audio.

- Because the Mixtool is inverting the phase of one split, as the flangers approach the same audio in both channels, the mid cancels (which gives through-zero flanging), and you’re essentially just hearing the sides.

- Choosing Normal split mode instead of Channel Split accentuates the mid cancellation. This can produce a dreamy, ethereal effect with instruments that you want to have come in and out of the mix in interesting ways.

- Offsetting the Mixtool gain by even just a little bit will reduce the cancellation when the audio coincides.

- Offsetting the Flanger Delay controls changes the sound—for example, there’s quite a difference between having a delay of 1 ms for one Flanger and 5 ms for the other, compared to the default of 2 ms for each one.

- I prefer offsetting the Speed controls so that one is slow, and the other faster. This helps randomize the sweeping effect.

- LFO Amount and Mix do what you’d expect.

- Setting Feedback to the same negative percentage has less intensity than setting them both to the same positive percentage, but try setting one for negative feedback, and the other for positive feedback.

- Altering Input Balance on the Dual Pan, with both Pan controls centered, changes the proportion of the two flangers in the audio output. When set fully to the left or right, the sound is like traditional flanging, based on the flanger settings in the left or right channel respectively.

- Centering both Dual Pan controls gives a traditional, mono flanging sound, with through-zero cancellation. Spreading the controls out further products psycho-acoustic panning effects that will make your head spin on headphones, but translate to speakers as well. Also when spread fully to the left and right, mid cancellation doesn’t happen. With playback over a mono system, the panning goes away, and you just get flanging.

- The controls interact—for example, changing the delay time will change the effect of the panning mentioned in the previous tip.

The bottom line is you can play with the controls for hours. Well, at least I could! If you come up with a cool sound, save it as a custom FX Chain. Given the variables, you might not be able to find that sound again.

Finally, there seems to be persistent confusion about how to handle downloaded FX Chains, like where to store them, and how to put them in custom folders. For answers to these and other questions about FX Chains, please check out the Friday Tip Fun Facts about FX Chains.

Download the Flanger Lab.multipreset FX Chain preset here

The Ampire Sweetener

I work a lot with amp sims, and I love ’em. Well, except for one thing: Almost all of the ones that involve distortion exhibit what I call “the annoying frequency.” It’s hard to describe, but when it’s removed, you can definitely tell what’s missing—kind of a whistling sound, but without a sense of pitch. I have no idea why this particular type of artifact happens. It doesn’t go away if I increase the sample rate, choose a different pickup, switch guitars, or change my socks. And it’s worse with some amp sims than others; when reviewing a [particular amp sim by a PreSonus competitor] and I made the product manager aware of the annoying frequency, a subsequent expansion pack included a parametric equalizer so users could notch it out.

Granted, the 3rd gen Ampire is light years ahead of the 1st gen, as well as a lot of other amp sims out there. But we can still make it better, because the goal of the Friday Tip is to make things better, right?!? Besides, I’m an unreasonably picky guitar player.

Adding the EQ

Download the preset Ampire Sweetener.preset , and load it into the Pro EQ2 (Just open the .zip and double click the .preset file to install). It will now have the curve shown in Fig. 1. Insert the Pro EQ2 after your Ampire amp and cab of choice, and the sound will magically lose its artifact.

You have every right to skeptical—after all, you are reading this on the internet—so let’s listen to an audio example. The first half is with the EQ following the MCM800 amp and 4×12 MFB cab. The second half is with the EQ bypassed, but everything else the same. Both examples in the audio file are normalized to the same level. I’m pretty sure you’ll hear the artifact in the second half. Another way to hear the difference is play some power chords, and bypass the EQ stages to hear what they contribute to the sound.

The EQ’s curve isn’t only about the dual notches. There’s no need for super-high or -low frequencies, so those are reduced as well. Also, because the notches are in the high frequencies, adding a slight treble shelf compensates for the reduced amount of highs.

Figure 2: Reduce the high-shelf level and the two notches to sound more like the original amp sim/cab tone.

Now, this doesn’t mean you’ll like the end result better. You might prefer the sound with the artifact, and that’s fine. However, the artifact persists through the various amps and cabs. Inserting the Ampire Sweetener EQ removes that common element, which emphasizes the unique character, and tonal quality, of the individual amps and cabs. However, you can also “split the difference” by dialing back the parameters outlined in white (Fig. 2).

Finally, if you use other amp sims, many (if not most) will also benefit from one or two steep notches at the output. They probably won’t be the same frequencies, but they’ll likely be pretty close. The bad news is quite a few of them have far more prominent artifacts than Ampire, but the good news is the higher level makes it easier to hear them, so you can dial in their frequencies more quickly to notch them out.

LCR Mixing and Panning Explained

Lately, it seems there’s an increasing buzz about “LCR” mixing. LCR stands for Left, Center, and Right, and it’s a panning technique where all panpots are set to either left, center, or right—nothing in between. Look it up on the internet, and you’ll find polarized opinions that vary from it’s the Holy Grail of mixing, to it’s ridiculous and vaguely idiotic. Well, I’m not polarized, so I’ll give you the bottom line: it can work well in some situations, but not so well in others.

Proponents of this style of mixing claim several advantages:

- The resulting mixes sound very wide without having to use image processing, because there’s so much energy in the sides.

- It simplifies mixing decisions, because you don’t have to agonize over stereo placement.

- Mixes translate well for those not sitting in stereo’s “sweet spot,” because the most important material is panned to the center.

- It forces you to pay attention to EQ and the arrangement, to make sure there’s good differentiation among instruments panned hard left and hard right.

- If an LCR mix leaves “holes” in the stereo field, then you can use reverb or other stereo ambience to fill that space. As one example, stereo overhead mics on drums can pan hard left and hard right, yet still fill in a lot of the space in the middle. Or, place reverb in the channel opposite of where a signal is panned.

There are plenty of engineers who prefer LCR mixes for the reasons given above. However, LCR is not a panacea, nor is it necessarily desirable. It also may not fit an artist’s goal. For those who think of music in more symphonic terms—as multiple elements creating a greater whole, to be listened to under optimal conditions—the idea of doing something like panning the woodwinds and brass far left and the violins full right, with orchestral percussion and double bass in the middle, makes no sense. Conversely, if you’re doing a pop mix where you want every element to be distinct, an LCR approach can work well, if done properly.

Then again, some engineers consider a mix to be essentially a variation on mono, because the most important elements are panned to center. They don’t want distractions on the left and right; those elements exist to provide a “frame” around the center.

Another consideration is according to all the stats I’ve seen, these days more people listen on headphones than component system speakers. LCR mixing can sound great at first on headphones due to the novelty, but eventually becomes unnatural and fatiguing. Then again, as depressing a thought as this may be, a disturbingly large part of the population listens to music on computer speakers. Any panning nuances are lost under those conditions, whereas LCR mixing can sound direct and unambiguous.

Help Is on the Way!

So what’s a mix engineer to do? Well, a good way to get familiar with LCR is to load up some of your favorite songs into Studio One, and listen to the mid and sides separately. Hearing instruments in the sides tends to imply an LCR mix; Madonna’s “Ray of Light” comes to mind. For a “pure” LCR mix, listen to the original version of Cat Stevens’ “Matthew and Son” on YouTube. It was recorded in 1966 (trivia fans: John Paul Jones, later of Led Zeppelin, played bass). Back then, the limited number of tracks, and mixing console limitations, almost forced engineers into doing LCR. In case you wondered why some songs of that era had the drums in one channel and the bass in the opposite channel…now you know why.

Anyway, it’s easy to do mid-side analysis in Studio One (Fig. 1).

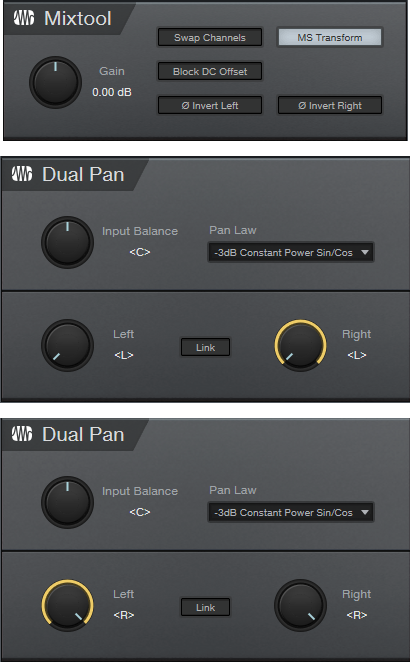

The Mixtool, with MS Transform selected, encodes a stereo signal into mid (left channel) and sides (right channel). However, it’s difficult to do any meaningful analysis with the mid in one ear and the sides in the other. So, the Dual Pan’s Input Balance control chooses either the mid <L> or sides <R>. The panpots place the chosen audio in the center of the stereo field.

Once you start finding out whether your favorite songs are LCR or mixed more conventionally, it will help you decide what might work best for you. If you decide to experiment with LCR mixing, bear in mind that it kind of lives by its own rules, and it takes some experience to wrap your head around how to get the most out of it.

And the Verdict Is…

Well, you can believe whatever you like from what you see on the internet, and more importantly, choose what sounds best to you…but this is my blog post, so here’s what I think ?. Any and all comments are welcome!

As mentioned in a previous blog post, I always start mixes in mono. I feel this is the best way to find out if sounds mask either other, whether some tracks are redundant because they don’t contribute that much to the arrangement, and which tracks need EQ so they can carve out their own part of the frequency spectrum. That way, whether instruments are on top of each other or spread out, they’ll work well together.

But from there on, I split my approach. I still favor the center and use the sides as a frame, but also selectively choose particular elements (usually rhythm guitar, keyboards, and percussion) to pan off to the left or right so there’s a strong presence in the sides. For me, this gives the best of both worlds: a wide mix with good separation of various elements, but done in service of creating a full mix, without holes in the stereo field. Those who listen on headphones won’t be subjected to an over-exaggerated stereo effect, while those who listen over speakers will have a less critical “sweet spot” than if there was nuanced panning.

I came up with this approach simply because it fits the kind of music I make, and the way I expect most people will listen to it. Only later did I find out I had combined LCR mixing with a more traditional approach, and that underscores the bottom line: all music is different, and there are few—if any—“one-size-fits-all” rules.

Well, with the possible exception of “oil the kick drum pedal before you press record.”