Category Archives: Studio One

Hi-Hat Humanizing

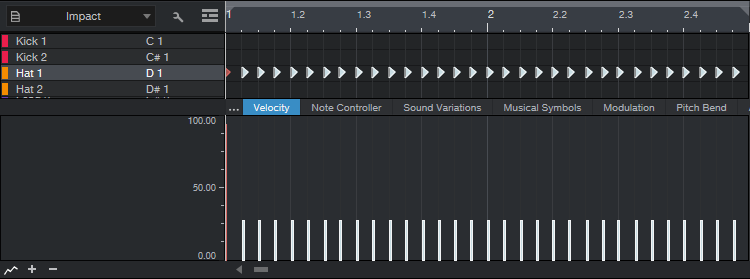

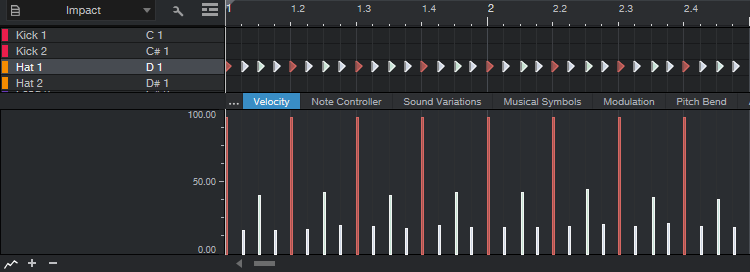

Nothing is more bothersome to me than a 16th note hi-hat pattern with a constant velocity—like the following.

Audio Example 1

“Humanizing,” which usually introduces random changes, attempts to add more interest. But human drummers don’t really randomize (unless they’ve had too many beers). Even if the beats are off a little bit, there’s usually some conscious thought behind the overall timing.

So, what works for me is a mix of deliberate tweaking and what I call “successive humanization,” which applies humanization more than once, in an incremental way. With hi-hats, my goal is rock solid downbeats to maintain the timing, slightly humanized offbeats, and the most humanizing on everything that’s not the downbeat or offbeat. This adds variety without negatively impacting the rhythm.

Let’s fix that obnoxious 16th-note pattern. To start, select all the notes, and bring them down to just below 30% (fig. 1).

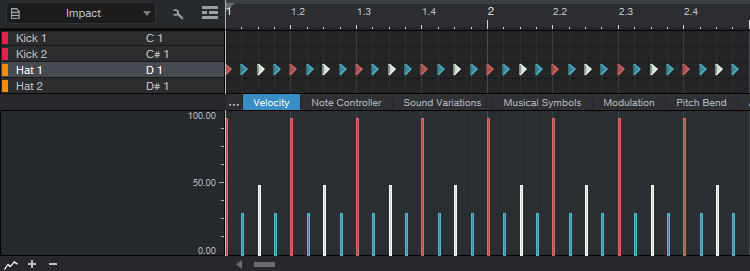

Next, we’ll use Macros to select specific notes for editing. Select all the notes, click on the Macro View button (between Q and Action), click Action in the Macro Edit menu, and choose Note Selection > Select Notes Downbeat. Raise all the downbeats to just below 95% or so. Then, choose Note Selection again, but this time select Offbeat, and raise the offbeats to just below 50%. Now your notes look like fig. 2.

The part sounds like this…we’re on our way.

Audio Example 2

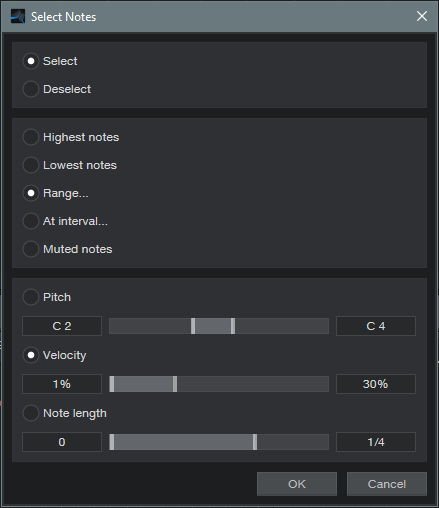

Close the Macro view. Now we’ll humanize the lowest-velocity notes a little bit. Select all the notes. Click on Action, and under Global, choose Select Notes. Choose Range, set Velocity from 1% to 30%, and click OK (fig. 3). This is why we wanted to set the notes slightly below 30%—to make sure we caught all of them in this step.

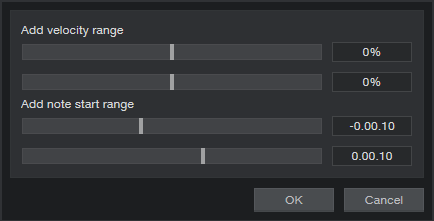

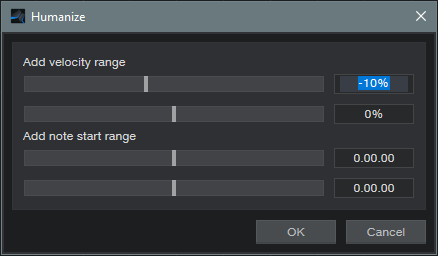

Choose Action > Humanize. We’re going to Humanize the notes downward a bit, so set Add Velocity Range to -10% and 0% (fig. 4).

Figure 4: Humanizing has been restricted to lowering velocities somewhere between 0% and -10%, but only for notes with velocities under 30%.

Let’s introduce some successive humanization. Click on Action, and again, Select Notes. Choose Range, set Velocity from 1% to 50%, and click OK. Now we’ll humanize velocity for the notes that were originally under 50% and also those that were under 30%. Humanize again to -10%, as done in the previous step. There’s a little more variety in the following audio example.

Audio Example 3

Now let’s humanize the start times a bit, but only for the notes below 50%—we want rock-solid downbeats. Select the notes under 50% as you did in the previous step, but this time, for the Humanize menu don’t alter velocity. Just humanize the start time between -0.00.10% and 0.00.10% (fig. 5).

Now our notes look like fig. 6. Look closely to see the changes caused by humanization.

And it sounds like…

Audio Example 4

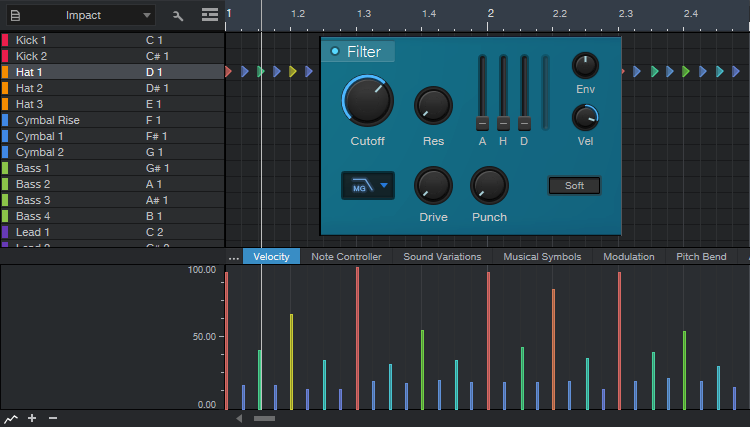

At this point, the Macros and humanization options have added some much-needed variations. Although I feel drum parts always need at least a little of the human touch, thanks to Studio One doing most of the work, at this point only a few small changes are needed. Also, a little filtering can make the harder hits brighter. (Tip: When editing the filter parameters, turning the Resonance way up temporarily makes the range that’s being covered far more obvious.) Fig. 7 shows the final sequence.

Figure 7: This adds a few manual velocity tweaks, along with filter editing to make higher-velocity sounds brighter.

The point of the filter was to give a more subdued hi-hat sound, as you’ll hear in the next audio example. If you want a more metronomic effect, you’d probably prefer the previous audio example…but of course, it all depends on context.

Audio Example 5

You can even try one final humanize on everything—a little velocity, and little start time—and see what happens. If you don’t like it…well, that’s why “undo” exists!

Add More Inputs to Your Audio Interface

I never liked patch bays. I certainly didn’t like wiring them, and I didn’t like having to interrupt my creative flow to patch various connections. In my perfect world, everything would patch to its own input and be ready to go, so that you never had to re-patch anything—just assign a track to an input, and hit record.

With enough audio interface inputs, you can do that. But many audio interfaces seem to default to 8 line/mic ins. This makes it easy to run out of inputs, especially as synth fanatics gravitate toward re-introducing hardware to their setups (and want to take advantage of Studio One 5’s Aux Channels). We’ll assume you don’t actually want to get rid of your interface with 8 mic/line ins…you just want more. There are three main solutions:

- Use a mixer with audio interfacing capabilities. A StudioLive will certainly do the job, but it could be overkill for a home studio, unless it’s also what you use for gigs.

- Aggregate interfaces. We’re getting closer—simply add another interface to work alongside your existing one. It’s easy to aggregate interfaces on the Mac using Core Audio, but with Windows, ASIO almost never works for this. So, you need to use Windows’ native drivers. The newer WASAPI drivers have latency that’s close to Core Audio, but aren’t widely supported. So, you may be stuck with the older (slooooow) drivers. Another issue is needing to give up another USB port for the second interface, and besides, using different applets to control different interfaces can be a hassle.

- ADAT optical interface. This is my preferred solution, which works with both Mac and Windows. It’s especially appropriate if you record at 44.1 or 48 kHz, because then you can add another 8 inputs per ADAT optical port. (At 88.2 or 96 kHz, you’re limited to 4 channels per port, and not all audio interfaces are compatible with higher sample rates for optical audio.)

Why ADAT Optical Is Cool

I started with a PreSonus Studio 192 interface, graduated to a PreSonus 1824c, but kept the Studio 192 as an analog input expander. The 192 has two ADAT optical ports, so it can send/receive 16 channels at 44.1 or 48 kHz over a digital audio “light pipe” connection. The 1824c has one ADAT port for input and one for output, so patching one of the Studio 192’s optical outs to the 1824c’s optical in gave a total of 16 analog inputs. This accommodates my gear without having to re-patch.

Another advantage is that the Studio 192 has +48V available for individual mic inputs, whereas the 1824c’s +48V option is global for all inputs. So, I can easily use a mix of ribbon, dynamic, and condenser mics with the 192, while leaving +48V off for the 1824c.

The interface being used as an “expander” doesn’t require a permanent USB connection to your computer (although you may need a temporary connection to change the interface’s default settings, if you can’t do that from the front panel). And, you don’t need an interface with lots of bells and whistles—just 8 inputs, and an ADAT out. A quick look at the used market shows plenty of ways to add another 8 channels to your audio interface for a few hundred dollars, although this could also be a good reason to upgrade to a better interface, and use the older one as an expander.

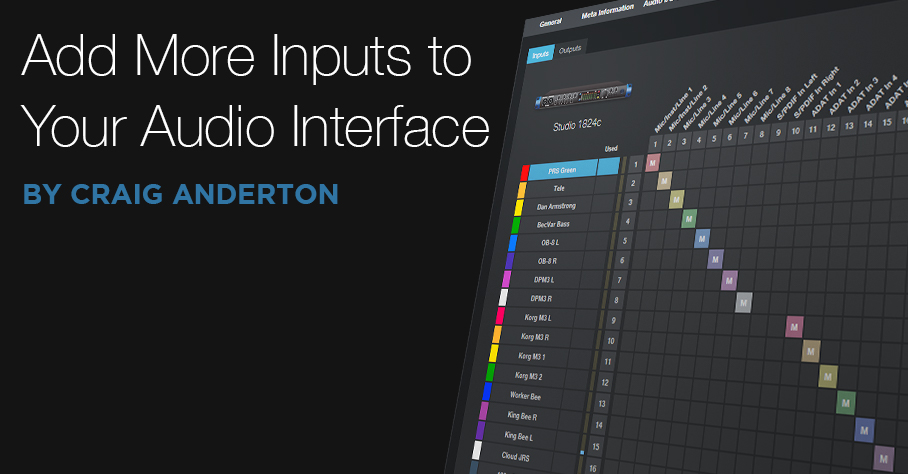

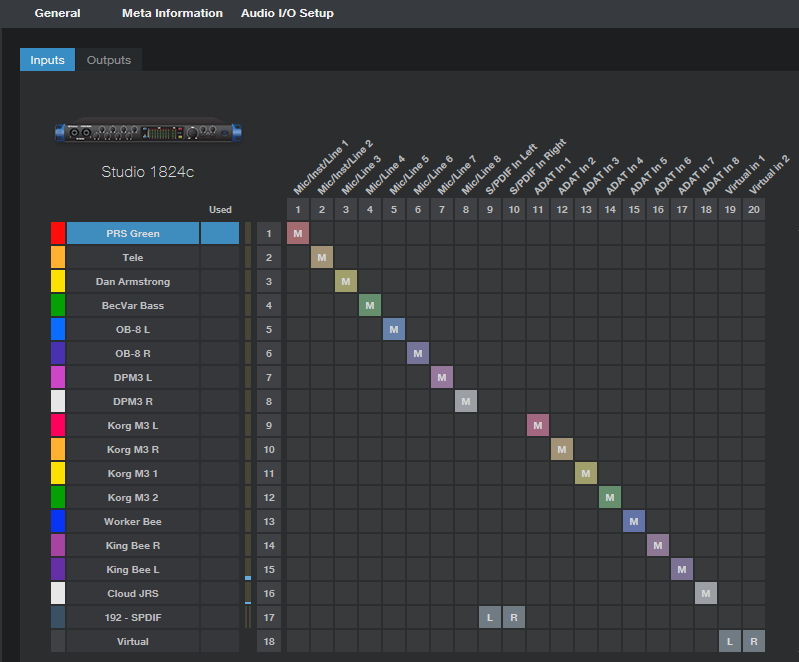

Because the 1824c has an ADAT input, both interfaces show up in the Song Setup menu. The inputs from the ADAT light pipe look, act, and are assigned like any other inputs (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: It even kind of looks like a patch bay, but I never have to patch any physical connections.

Time for a Caution…

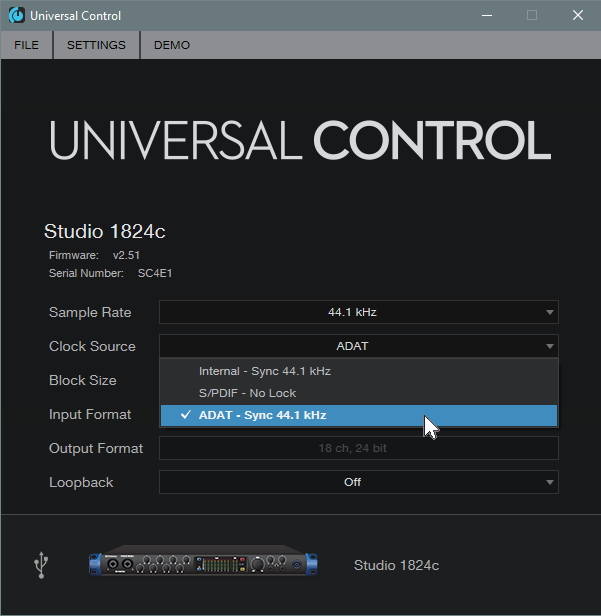

…and that caution involves timing. Always set the ADAT expander as the master clock, so that it’s transmitting clock signals to the main interface, which is set to receive the clock (Fig. 2). If the main interface is the master, then the expander will be free-running and unsynchronized. The audio will seem to work, but you’ll get occasional pops and clicks when the units drift out of sync (which they will do over time).

Patch bays? Who needs ’em? I like virtual patch bays a lot more.

Claim Your 342 Free Ampire Cabs

Add the cabs from the 3rd gen Ampire with the ones from the High-Density expansion pack, and you have 19 cabs.

Surprise! You actually have 342 cabs. Not all of them sound fabulous, but some do—especially if you throw a Pro EQ into the mix. What’s more, with clean sounds, the new cabs give “varitone”-like filtering effects that almost sound like you have an infinite supply of different bodies and pickups. We’ll show how to take advantage of these new cabs with Studio One’s Pro and Artist versions.

How It Works (Pro Version)

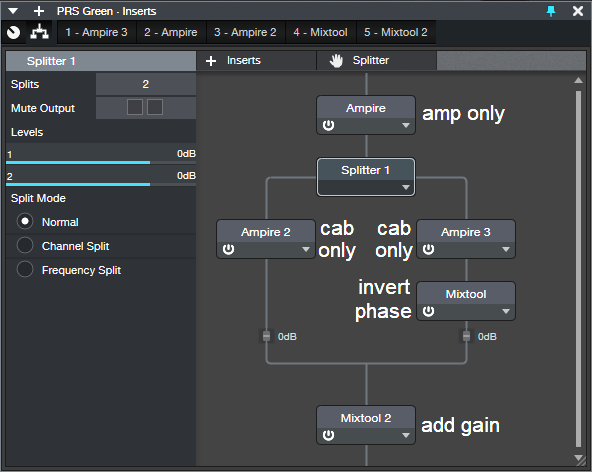

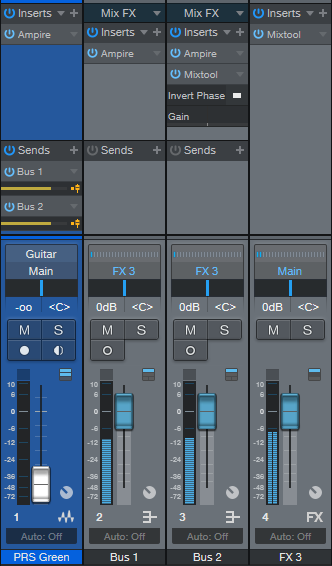

With Pro, the Splitter is the star (fig. 1). The Ampire at the top provides your amp sound (optionally with effects), but don’t load a cabinet. Split the amp’s output into two parallel paths, each with an Ampire that has only a cabinet (no amps or effects). Insert a Mixtool in one of the parallel paths, and click its Invert button.

If you select the same cab for both parallel paths, you won’t hear anything, because they cancel. But with two different cabs, what they have in common cancels, while their various modeled resonances remain. This creates the sound of a different, distinctive cab. Of course, you can also play with the cab mic positions to generate even more possible sounds…the mind boggles.

Finally, add another Mixtool at the output so you can increase the gain. This compensates for the reduced level due to one path being out of phase. If you want to add a Pro EQ (recommended), insert it before the Mixtool.

How It Works (Artist Version)

Fig. 2 shows how to set up busing to do this in Artist, although Pro users might prefer this option because the editable elements are more exposed.

- The Ampire in the PRS Green channel (which has an amp only, with no cab) has one send that goes to Bus 1, which has a cab-only Ampire.

- Another send goes to Bus 2, with another cab-only Ampire, as well as a Mixtool to invert the phase.

- The Bus 1 and 2 outputs go to the FX3 channel, which sums the standard and out-of-phase cabs together. The FX3 channel also has a Mixtool to provide makeup gain.

Note that if you choose the same cab for the Ampires in Bus 1 and Bus 2, and your original channel’s fader (in this case, PRS Green) is all the way down, you should hear nothing due to the cancellation. If you hear something, either the sends to the buses, the bus levels, Ampire output controls, or mic settings are not identical for the two channels.

But Wait—There’s More!

The composite cab sound in the FX3 bus can often benefit from adding a Pro EQ before the final Mixtool. Typically you’ll roll off the bass, or make the treble less bright, depending on the cabs. And again, let me remind you to try this with clean sounds—it’s sort of like out-of-phase pickup wiring, but with hundreds of options.

One limitation is that there’s no way to change cabs with a control panel knob or with automation. To explore the various sounds, choose a cab for the Ampire in one of the buses, then run through the cabs in the other bus’s Ampire. Some sounds won’t be all that useful, others will be distinct and novel, and some that don’t appear to be useful at first come into their own with just a touch of EQ.

Want an audio example? Sure. This combines the VC 20 and with an out-of-phase British II, with a little low-frequency rolloff. The Open Air reverb uses an impulse from my Surreal Reverb Impulse Responses pack. You’re on your own for checking out the other 341 combinations!

When you find a combination of cabs that works, write it down—with this many cabs to choose from, you might not find it again.

So…What Does the CTC-1 Really Sound Like?

Good question, because the effect is subtle. If you play with the various controls while listening to a mix, you can tell that something is different, but you may not know exactly what. So, let’s find out what the CTC-1 actually contributes to the sound.

Bear in mind that Mix FX work across multiple buses, and the overall effect depends on the audio being sent through them, as well as the control settings. So while this tip can’t tell you what the CTC-1 will sound like under various conditions, you’ll get a sense of the character associated with each of the CTC-1’s mixer emulations. Note that the audio examples are not mixed songs, but only the effect added by the CTC-1 to mixes, and amplified so you can hear the effect clearly.

Also, it doesn’t look like PreSonus is letting up on Mix FX development any time soon (PortaCassettes and Alps, anyone?), so this tip should be handy in the future as well.

The Test Setup

- Load a track with a stereo mix of a song you like.

- Duplicate (complete) the track, and invert the copy’s polarity (phase). To invert the polarity, you can insert a Mixtool and click on the Invert Left and Invert Right buttons. Or enable the channel’s Input Controls, and flip the polarity with those (as shown in fig. 1).

- Insert a Bus, and assign the out-of-phase track’s output to the Bus input. The Bus output goes to the Main output, as does the in-phase track output. Make sure the Main output’s Mix FX is set to None.

- Set all faders to 0 dB, and start playback. With the Bus’s Mix FX set to None, you should hear nothing—the only audio sources are the original track, and the out-of-phase track playing back through the Bus. If you hear anything, then the faders are not at the same levels, the out-of-phase track is somehow getting into the Main bus, or the Main bus has a Mix FX enabled.

Now you can check out various CTC-1 mixers. Fig. 2 shows the default setting used for the tests. In the audio examples, the only changes are setting the Character control to 1.0, or to 10. 1.0 is the most faithful representation of the console being emulated, while 10 adds the equivalent of a sonic exclamation mark.

Let’s Start Testing!

Note that there’s a continuum of Character control settings between 1.0 and 10. Settings other than those in the audio examples can make a major difference in the overall sound, and you can really hear them with this kind of nulling test.

Here’s what the Classic mixer sounds like. Its main effect is in the midrange, which a Character setting of 10 really emphasizes. Among other things, this gives a forward sound for vocals.

The Tube sound kicks up the low end, but turning up the Character control emphasizes a slightly higher midrange frequency than the Classic sound, while retaining the bass.

The Custom mixer is about adding brightness mojo and bass. Bob Marley would probably have loved this. Turning up Character emphasizes lower midrange frequencies than the other two.

Snake Oil, or the Real Deal?

I don’t have the mixers on which these settings were modeled, so I can’t say whether this is the real deal. But I can say it’s definitely not snake oil. The effect is far more nuanced then just EQ, and the audio examples confirm that Studio One owners who say the CTC-1 adds some kind of mysterious fairy dust are right…it does add some kind of mysterious fairy dust.

These audio examples should make it easier to get the sound you want. For example, if you like the way the Custom hits the bass and treble, but it’s a bit much, then simply turn up the Character control for a little more midrange. If your mix is already pretty much where you want it, but it needs to pop a bit more, the Classic is the droid you’re looking for. The Tube really does remind me of all those years I spent on tube consoles, especially if I turn up Character a little bit.

Sure, you just turn select mixer emulations, and play with controls, until something sounds “right.” But I must say that running these tests have made it much easier to zero in, quickly, on the sound I want.

Combi-Band Processing

I’m a big fan of multiband processing, and setting the Splitter to split by frequency makes this easy. However, there’s more to life than bi-amping or multiband processing—so let’s look at what I call “combi-band processing.” It gets its name because although the signal is split into three frequency bands, the low and high bands are combined, and processed by a single effect. Meanwhile, a second effect processes the mid band.

Bi-amping is great for amp sims (choose the best amp for lows, and the best for highs). I find it doesn’t work so well for effects, because when you split an instrument (like guitar) into only lows and highs, many effects aren’t all that useful for low frequencies. But if you raise the crossover frequency so that the low effect covers a wider range of frequencies, then there aren’t enough high frequencies for the effect that processes the highs.

With the combi-band approach, one effect handles the all-important midrange frequencies, while the other processes the low and highs. As a result, both effects have an obvious impact on the sound—as you’ll hear in the audio example. This also results in a simpler setup than three or more discrete bands of processing.

Combi-Band Processing FX Chain

Apologies to Artist aficionados…this one requires Studio One Pro, because of the Splitter’s frequency-split talents. However, I’m trying to figure out an easy way to do this in Artist. If it works, you’ll see it in a future tip.

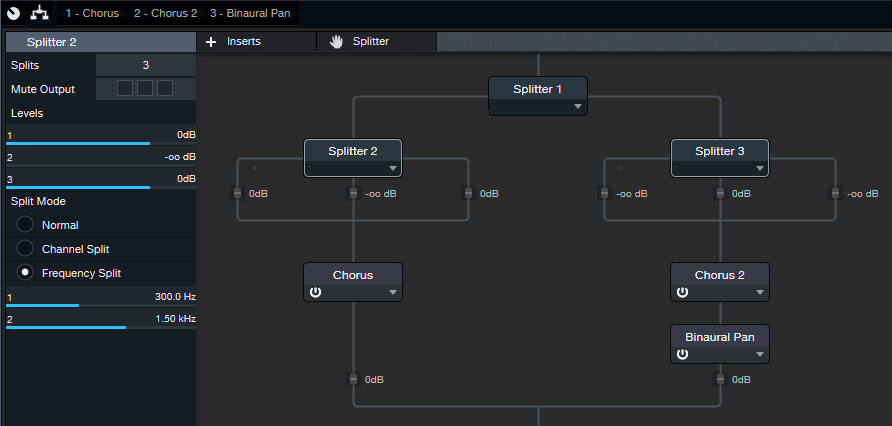

The FX Chain starts with a Splitter in Normal Mode, which feeds two Splitters in Frequency Split mode (fig. 1)

Figure 1: The FX Chain for Combi-Band Processing. The Chorus and Pan effects aren’t part of the process, but are the ones used in the audio example. Of course, other effects are just as suitable.

Both Splitters have almost identical parameters, including the split frequencies. In this case, they’re set to 300 Hz and 1.5 kHz, which seem to work well with guitar. Tweak the split frequencies as needed to optimize them for different instruments.

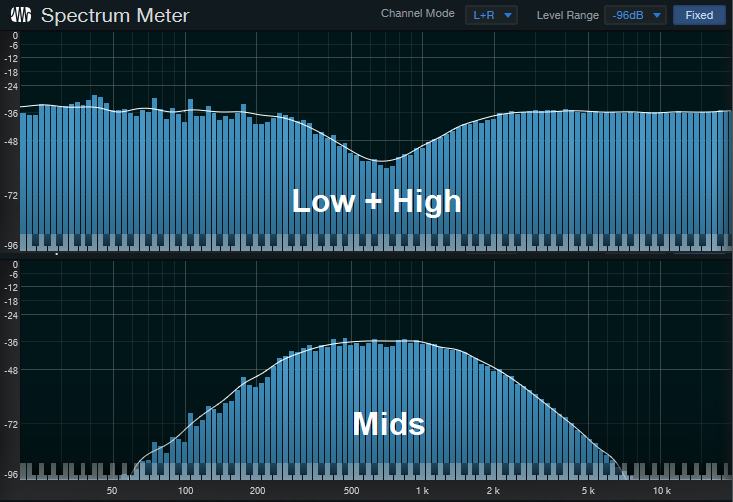

The parameters that differ are the various level controls. The level is pulled down for the middle band in Splitter 2, so its output consists of only the low and high frequency bands. Meanwhile for Splitter 3, the level for the low and high frequency bands is pulled all the way down, so its output consists of only the middle band. Fig. 2 shows what happens when you inject pink noise into the effects chain, and monitor the outputs of the two splitters.

Figure 2: The top view shows Splitter 2’s frequency response, while the bottom view shows Splitter 3’s frequency response. If you sum these together, the response is flat.

About the Audio Example

Let’s listen to an example of Combi-Band Processing in action. There are three audio snippets. The first one is the midrange frequencies only, going through the Chorus, which is set to a fairly fast speed. The second snippet is the low and high frequencies only. It also goes through a Chorus, but set to Doubler mode. A Binaural Pan follows this to widen out the highs and lows.

The final snippet is the sound of combining the two paths together, which creates a gorgeous, rich chorusing sound. But plenty of other effects work well, like tempo-synched tremolos set to different LFO frequencies or waveforms, echoes with different delay times or feedback amounts, reverb on only the mids and echo on the highs and lows…you get the idea. So combi-up, and check out a different twist on signal processing.

Slapback Echo—Elvis Lives!

John D. made a comment in my Sphere workspace, which hosts the companion files for The Huge Book of Studio One Tips and Tricks: “How about a tip on how to create the original Elvis echo from his Sun Studios days? I really love that sound.” Well John, we take requests around here! So here ya go.

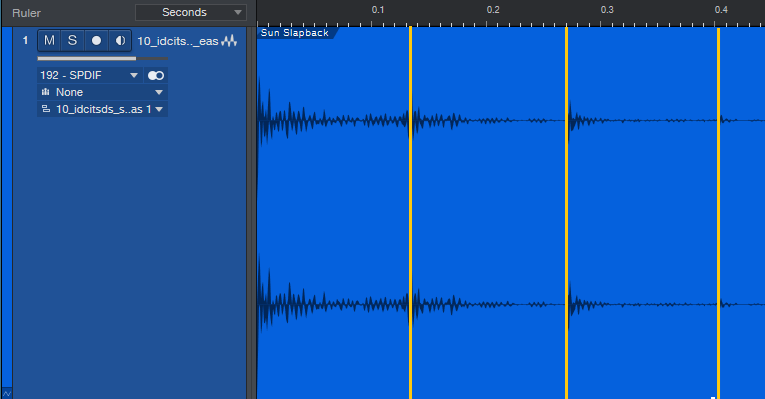

I asked the internet if anyone knew the time in ms for the slapback echo Elvis used. The various answers didn’t seem right, so I went to the source, and analyzed Elvis Presley’s “I Don’t Care if the Sun Don’t Shine” and as well as Carl Perkins’ “Her Love Rubbed Off” (he also recorded at Sun Studios). After measuring the duration for three repeats and dividing by 3, the answer was around 135 ms (fig. 1).

The analog delay has all the parameters needed to achieve this sound (fig. 2).

The time is, of course, 135 ms. Feedback is 0.0%, because the echo was run through a separate tape recorder. It didn’t sound like the echo was being re-routed back to the input on the recordings I heard, but it might have been, and later recordings did do this…so choose what works best for you.

The Color controls are important. I pulled back the lows just a bit, as well as the highs, because 7.5 IPS recorders don’t have as crisp a high-frequency response as 15 IPS machines (but who knows how the echo tape machine was aligned?). When you listen to these recordings, you’ll often notice some distortion, so kick up the Drive control as desired. 6.0% was about right for my taste. Adjust Dry/Wet for the desired amount ratio of echo to dry sound.

You’re probably wondering about the Speed and Amount controls. I decided what the heck, I’d add some mechanical tape flutter. 15 Hz corresponds to 7.5 IPS, and the amount seemed reasonable.

Does it really sound like that famous echo effect? Well, at the risk of great (and possibly irreversible) public embarrassment, I donned an Elvis impersonator outfit, put on 50 pounds, and did my approximation of a 50s-style vocal for “That’s All Right, Mama.” True, I didn’t write the song—that honor goes to Arthur Crudup, who recorded it in 1946. But it’s under 30 seconds, for educational purposes, transformed (done digitally by someone who doesn’t sound even remotely like Elvis), and doesn’t diminish the market value of the music. I think we’re cool from a Fair Use standpoint.

And there you have your vintage slapback echo. Yes, I do take requests—I’ll be here all week, don’t forget to tip your servers, and remember, every Thursday night the Chez PreSonus eatery in Baton Rouge has its famous 2-for-1 gumbo special! See you soon.

Studio One Sings!

Let’s get one thing straight: yes, I did promise a tip of the week. But, I specifically didn’t promise it would be normal. Besides, I know some EDM fans are just going to love this one. And with plenty of creative Studio One aficionados out there, who knows what you’ll do with this…

I wanted to see if it was possible to use a simple, no-cost text-to-speech synthesizer, create a phrase, load it into Studio One, and tune it with the Chord Track. While the results won’t be mistaken for Realitone’s Blue, this setup can do some cool tricks—check out the audio example, with a vocal that’s not being sung by a human.

Generating the Speech

This all started because a person who had bought The Huge Book of Studio One Tips and Tricks mentioned that you could load the PDF into Microsoft Edge (which is cross-platform). Then if you invoked Edge’s Read Aloud function, the program would read the text to you. Say what? I had to try it.

There are plenty of text-to-speech converters, including ones built into MacOS and Adobe Acrobat. Extensions are available for various browsers, and there are cloud-based text-to-speech services. But Microsoft Edge’s implementation is a great way to get started—just open a PDF doc in Edge. (Non-PDF docs will have to be converted or exported first; you can always use a free option, like Open Office.) Select what you want it to read, and then click on Read Aloud. The fidelity is excellent, and you can speed up or slow down the reading speed.

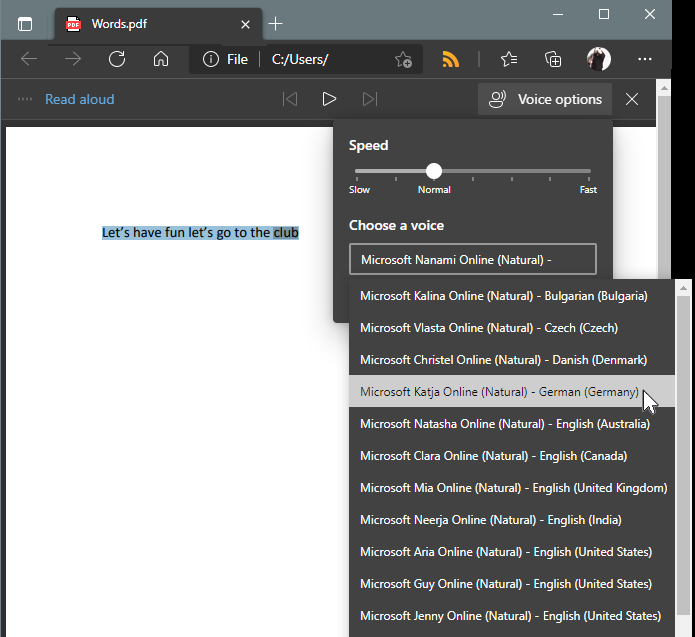

There are 10 different English speakers, but if you choose one of the other 28 languages, depending on the language, they’ll read English with an accent (fig. 1). Of course, these languages are meant to read texts in their native language, but who cares? I used Katja, the German speaker, for the audio example. She speaks English quite well.

Next, you need to get the speech output into Studio One. I have a PreSonus 1824c interface running on a Windows computer, and in that scenario, all that’s necessary is enabling the virtual input while Edge reads the words. Just remember that when you record the audio, to avoid feedback, don’t enable Input Monitor for the track you’re recording—just listen to the virtual input.

In addition to third-party apps that capture audio, the Mac has a fun way to generate speech. Open TextEdit, and write (or load) the text you want. From the TextEdit menu, choose Services > Services Preferences. Next, click Services in the keyboard shortcuts pane. In the right pane, scroll down to Text, and check its box. To create a recording, which you can bring into Studio One, select the text, go to the TextEdit menu again, and under Services, choose Add to iTunes as a Spoken Track. When you initiate the text-to-speech process, the audio file will be saved in the album you specify.

If all else fails, patch the audio output from a device that produces speech, to an audio input for Studio One.

Editing the Voice

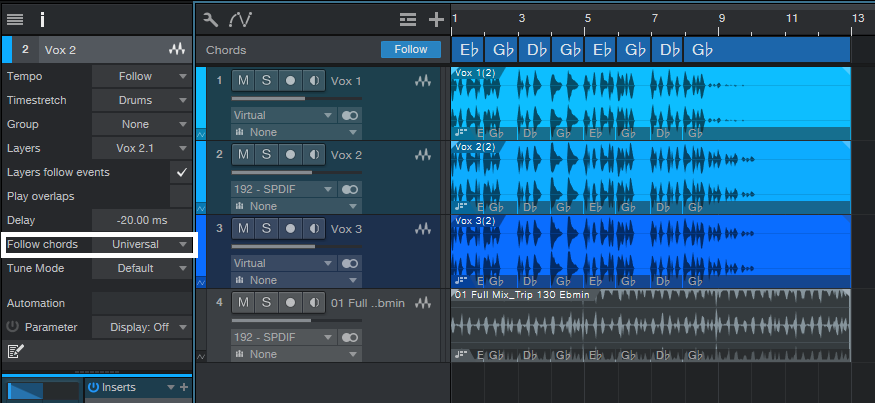

Once the voice was in Studio One, I separated the words to place them rhythmically in relation to the Musicloop. Copying the vocal two more times allowed for panning, timing shifts (one track -20 ms, one track +20 ms, one with no shift), and reverb. To give a sense of pitch, the vocal tracks followed the Chord Track in Universal mode (fig. 2). If you want to get really granular, Melodyne does an outstanding job of varying inflections.

That’s really all there is to it. I just know someone is going to figure out how to use this to create some cool novelty song, it will be a big hit, get zillions of streams, and shower a Studio One user with riches and fame. That’s why it’s so important to read the Friday Tip every week ?

Why the Performance Monitor Is Cool

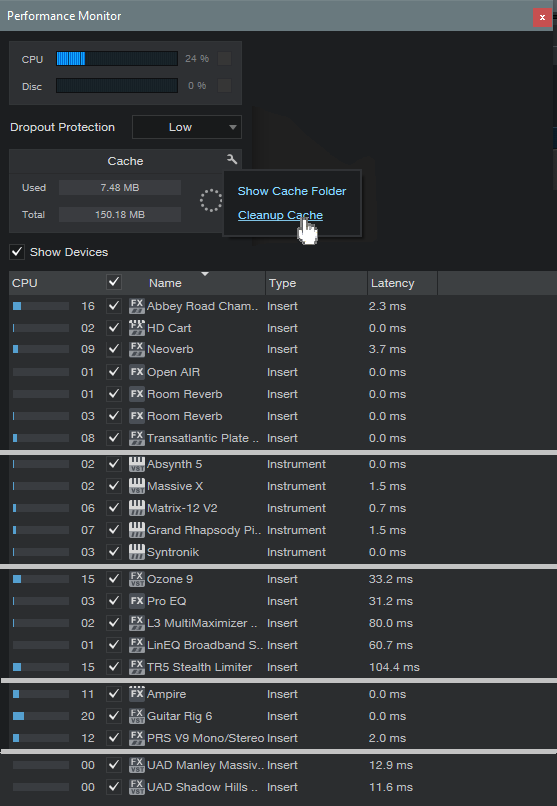

Ever wonder why inserting a particular plug-in makes the latency go through the roof? Which tracks you should transform because they require a lot of CPU power, and which ones aren’t a problem? The Performance Monitor, accessed via View > Performance Monitor, reveals all

But this isn’t just about interesting information. The Performance Monitor will help you decide which block settings to use, whether native low-latency monitoring will work for you, what level of dropout protection is appropriate, and more. Then, you can make intelligent tradeoffs to process audio in the most efficient way, while optimizing system stability.

Start at the the Top

Referring to fig. 1, the readout at the top indicates CPU and disk activity. Check this periodically to make sure you aren’t running your CPU up against its limits. This can lead to audio crackles, dropouts, and other potential glitches. You can also set the level of dropout protection here.

Figure 1: The Performance Monitor window (the UI has been modified somewhat to make analyzing the data easier).

The Cache readout lets you know if you’re wasting storage space. The Cache accumulates files as you work on a song, but many of these files are only temporary. If you invoke Cleanup Cache, Studio One will reclaim storage space by deleting all unused temp files in the cache. If you have lots of songs and haven’t cleaned out their caches, you might be surprised at how much space this frees up. I usually wait until I’m done with a song before cleaning it up.

Finally, there’s a list of all the plug-ins that are in use. The left-most column shows much relative CPU power a plug-in consumes, as a bar graph, and numerically. The next column to the right shows the plug-in name and format. The Type column shows whether the plug-in is an instrument or insert effect. The final column on the right shows the delay compensation a plug-in requires.

(Note there’s also a column that shows the plug-in “path,” which is the track where the plug-in resides. For effects, it also shows the effect’s position in the insert section. However, fig. 1 doesn’t show this column, because it takes up space, and doesn’t really apply to what we’re covering.)

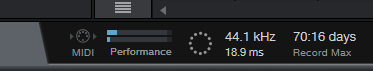

The transport includes a performance summary (fig. 2). Toward the lower left, you’ll see meters for CPU consumption (top meter) and disk activity. Click on Performance to call up the Performance Monitor window. The circle of dots indicates writing activity to the cache. Also note the figure under the sample rate—this is the total time Studio One has added for plug-in compensation.

Analyzing the Data

I’ve altered the UI graphic a bit, by grouping plug-ins, and adding a line in between to separate the groups. This makes it easier to analyze the data.

The top group includes a variety of reverbs, which in general tend to consume a lot of CPU power. Waves Abbey Road Chambers, iZotope’s Neoverb, and Rare Signals Transatlantic Plate clearly require the most CPU. Neoverb and Abbey Road Chambers also require the most latency compensation.

HD Cart is more efficient than I would have expected, and Studio One’s reverbs give a good account of themselves. Open Air and Room Reverb in Eco mode are extremely efficient, registering only 01 on the CPU meter. However, bumping up Room Reverb to HQ mode registers 03.

Bear in mind that lots of CPU consumption doesn’t mean a poor design—it can mean a complex design. Similarly, minimal CPU consumption doesn’t mean the effect won’t be as nuanced; it can simply mean the effect has been tightly optimized for a specific set of tasks. Also note that CPU-hungry reverbs are good candidates for being placed in an FX Channel or Bus. If used in individual tracks, Transform is your friend.

The next group down compares virtual instruments. You’ll see a fair amount of variation. I didn’t include the native Studio One instruments, because none of them requires delay compensation. Mai Tai and Presence typical register 01 or 02 in terms of CPU consumption, while the others don’t move the CPU meter noticeably. Bottom line: if you want to have a lot of instruments in a project, use as many native Studio One versions as possible, because they’re very efficient.

The next group down is plug-ins that use phase-linear technology. All of these require large amounts of delay compensation, because the delay is what allows for the plug-in to be in-phase internally. The Pro EQ2’s reading (which alternates between 3 and 4) is for only the phase-linear stage enabled; the nonlinear EQ stages draw very little CPU power. This is what you would expect from an EQ that has to be efficient enough to be inserted in lots of tracks, as is typical in a multitrack project.

The next-to-the-last group is amp sims. The figures vary a lot depending on which amps, cabinets, and effects are in use. For example, the Guitar Rig 6 preset includes two of their new amps, in HQ mode, that use a more CPU-intensive modeling process. The PRS V9 doesn’t have a lot of bells and whistles, but concentrates on detailed amp sounds—hence the high CPU consumption. Ampire is somewhat more efficient than most high-quality amp sims, but there’s no avoiding the reality that good amp sims consume a lot of CPU power—which is another reason to become familiar with the Transform function.

Finally, the last group shows why even with today’s powerful computers, there’s a reason why people add Universal Audio’s DSP hardware to their systems. Both the Manley Massive Passive and Shadow Hills compressor draw a lot of power, and require significant delay compensation. But, they don’t draw any power from Studio One, because they get their power from UA’s DSP cards, not your computer’s processor.

It’s interesting to compare plug-ins. You’ll sometimes find that free plug-ins draw a fair amount of CPU because they’re not optimized as tightly as commercial products. You’ll also see why some plug-ins will bring your computer to its knees, while others won’t.

All this reminds me of a post I saw on a forum (not Studio One’s) where a person had just bought a powerful new computer because the old one crashed so much. However, the new one was still a “crashfest”—so he decided the DAW was the problem, and it must have been coded by incompetents. A little probing by other forum members revealed that he really liked iZotope’s Ozone, so he put it on almost every track instead of using a more standard compressor or limiter. Oh, and he also used a lot of amp sims. Ooops…I’m surprised his CPU didn’t melt. If he’d had Studio One, though, and looked at the Performance Monitor, he would have found out how to best optimize his system…and now you can, too.

The Multiband Limiter

Although Studio One offers multiple options for dynamics control, there’s no “maximizing” processor, as often implemented by a multiband limiter (e.g., Waves’ L3 Multimaximizer). The Tricomp and Multiband Dynamics come close, but they’re not quite the same as multiband limiting—so, let’s use Studio One Professional’s toolset to make one.

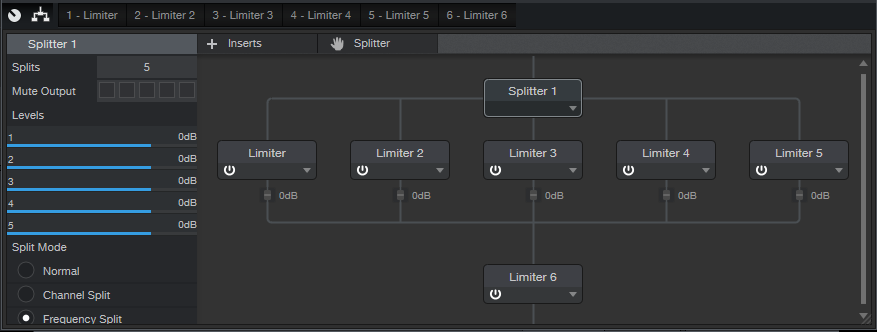

The concept (fig. 1) is pretty simple: use the Splitter in Frequency Split mode, and follow each split with a Limiter2. The final limiter at the end (Limiter 6) is optional. If you’re really squashing the signal, or choosing a slower response, the output limiter is there to catch any transients that make it through the limiters in the splits.

The Control Panel with the Macro controls (fig. 2) is straightforward.

Figure 2: The Macro controls adjust the controls on the five Limiter2 processors that follow the splits.

Each Macro control corresponds to the same control in the Limiter2, and varies that control over its full range, in all the Limiter2 modules that follow the splits. For example, if you vary the Threshold Macro control, it controls the Threshold for all limiters simultaneously (except for Limiter 6 at the output, which has “set-and-forget” settings), over the control’s full range. However, you can get even more out of this FX Chain by opening up the Limiter2 GUIs, and optimizing each one’s settings. For example, using less limiting in the lower midrange can tighten up the sound.

You can download the multipreset from my public PreSonus Sphere area, so you needn’t concern yourself with the details of how it’s put together (although you might have fun reverse-engineering it). And is it worth the download? Well, check out the audio example. The first and second parts are normalized to the same level, but the second one is processed by the multiband limiter. Note that it has a louder perceived level, and is also more articulated. This is because each band has its own dedicated limiter. I rest my case!

Bonus Supplementary Nerd Talk

The Splitter’s filters are not phase-linear, which colors the sound. There’s an easy way to hear the effects of this coloration: Insert a mixed, stereo file in a track, then copy it to a second track. When you play the two together, they should sound the same as either track by itself—just louder.

Next, insert a Splitter in one track, select Frequency Split, and choose 5 splits. Play the two tracks together, and you’ll hear the result of the phase differences interacting. Choosing a different number of splits changes the tonality, because the phase shifts are different.

This is why for mastering, engineers often prefer a phase-linear, multiband limiter—the sound is transparent, and doesn’t have phase issues. The downside of phase-linear EQ is heavier CPU consumption, and increased latency. But it’s equally important to remember that phase issues are an inherent part of vintage, analog EQ, which have a “character” that phase-linear EQs don’t have.

So as usual, the bottom line isn’t choosing one over the other—it’s choosing the right tool for the right job. If you’ve worked only with phase-linear multiband limiters, give this variation a try. With some material, you may find it doesn’t just give more perceived level, but also, gives a more appropriate sonic character.

Sound Design for the Rest of Us

Last May, I did a de-stresser FX Chain, and several people commented that they wanted more sound design-oriented tips. Well, I aim to please! So let’s get artfully weird with Studio One

Perhaps you think sound design is just about movies—but it’s not. Those of you who’ve seen my mixing seminars may remember the “giant thud” sound on the downbeat of significant song sections. Or maybe you’ve noticed how DJs use samples to embellish transitions, and change a crowd’s mood. Bottom line: sound is effective, and unexpected sounds can enhance almost any production

It all starts with an initial sound source, which you can then modify with filtering, delay, reverb, level changes, transposition, Chord Track changes, etc. Of course, you can use Mai Tai to create sounds, but let’s look at how to generate truly unique sounds—by tricking effects into doing things they’re not supposed to do

Sound Design Setup

The “problem” with using the stock Studio One effects for sound design is…well, they’re too well-designed. The interesting artifacts they generate are so low in level that most of the time, we don’t even know they exist. The solution is to insert them in a channel, amplify the sound source with one or two Mixtools set to maximum gain, and then enable the Channel’s Monitor button so you can hear the weirdo artifacts they generate. Automating the effects’ parameters takes this even further.

However, now we need to record the sounds. We can’t do this in the normal way, because there’s no actual track input. So, referring to fig. 1, insert another track (we’ll call it the Record Trk), and assign its input to the Effects track’s output. Both tracks need to be the same format – either both stereo, or both mono. (Note that you can also use the Record track’s Gain Input Control to increase the effect’s level.) Start recording, and now your deliciously strange effects will be recorded in the new track.

The FX channel is optional, but it’s helpful because the Effects track fader needs to turned way up. With it assigned to the Main bus, we’ll hear it along with the track we’re recording. That’s not a problem when recording, but on playback, you’ll hear what you recorded and the Effects track. So, assign the Effects output to a dummy FX bus, turn its fader down, and now you’ll hear only the Recorded track on playback. The Record Trk will still work normally when recording the sound effects.

After recording the sounds, normalize the audio if needed. Finally, add envelopes, transpose the Event (this can be lots of tun), and transform the effect’s sound into something it was never intended to do. Percussion sounds are a no-brainer, as are long transitions from one part of a song to the next. And of course, the Event can follow the Chord Track (use Universal mode).

The Rotor is a fun place to start. Insert it in the Effect track, and run through the various presets. Some DJs would just love to have a collection of these kinds of samples to load into Maschine. Here’s an audio example.

Audio Example 1 Rotor+Reverb

The next example is based the Flanger.

Audio Example 2 Flanger

Now we’ll have the previous Flanger example follow a strange Chord Track progression, in Universal mode.

Audio Example 3 Flanger+Chord track

Other Effects

This is just the start…check out what happens when you automate the Stages parameter in the Phaser.

Audio Example 4 Phaser Loop

Or turn the Mixverb Size, Width, and Mix to 100%, then vary damping. The Flanger is pretty good at generating strange sounds, but like some of these, you’ll have the best results if you set the track mode to mono. OpenAIR is fun, too— when you want a pretty cool rocket engine, load the Air Pressure preset (under Post), set Mix to 100% wet, add some lowpass filtering…and blast off!