Tag Archives: Craig Anderton

Friday Tips: The Limiter—Demystified

Conventional wisdom says that compared to compression, limiting is a less sophisticated type of dynamics control whose main use is to restrict dynamic range to prevent issues like overloading of subsequent stages. However, I sometimes prefer limiting with particular signal sources. For example:

- For mixed drum loops, limiting can bring up the room sound without having an overly negative effect on the drum attacks.

- With vocals, I often use a limiter prior to compression. By doing the “heavy lifting” of limiting peaks, the subsequent compressor doesn’t have to work so hard, and can do what it does best.

- When used with slightly detuned synth patches, limiting preserves the characteristic flanging/chorusing-like sound, while keeping the occasional peaks under control.

- Limiting is useful when following synth sounds with resonant filters, or with instruments going through wah or autofilter effects

THE E-Z LIMITER

Some limiters (especially some vintage types) are easy to use, almost by definition: One control sets the amount of limiting, and another sets the output level. But Studio One’s limiter has four main controls—Input, Ceiling, Threshold, and Release—and the first three interact.

If the Studio One Limiter looked like Fig. 1, it would still take care of most of your needs. In fact, many vintage limiters don’t go much beyond this in terms of functionality.

Figure 1: If Studio One’s Limiter had an “Easy Mode” button, the result would look something like this.

To do basic limiting:

- Load the Limiter’s default preset.

- Turn up the input for the desired limiting effect. The Reduction meter shows the amount of gain reduction needed to keep the output at the level set by the Threshold control (in this case, -1.00 dB). For example, if the input signal peaks at 0 dB and you turn up the Input control to 6 dB, the Limiter will apply 7 dB of gain reduction to keep the Limiter output at -1.00.

Note that in this particular limiting application, the Threshold also determines the maximum output level.

THE SOFT CLIP BUTTON

When you set Threshold to a specific value, like 0.00 dB, then no matter how much you turn up the Limiter’s Input control, the output level won’t exceed 0.00 dB. However, you have two options of how to do this.

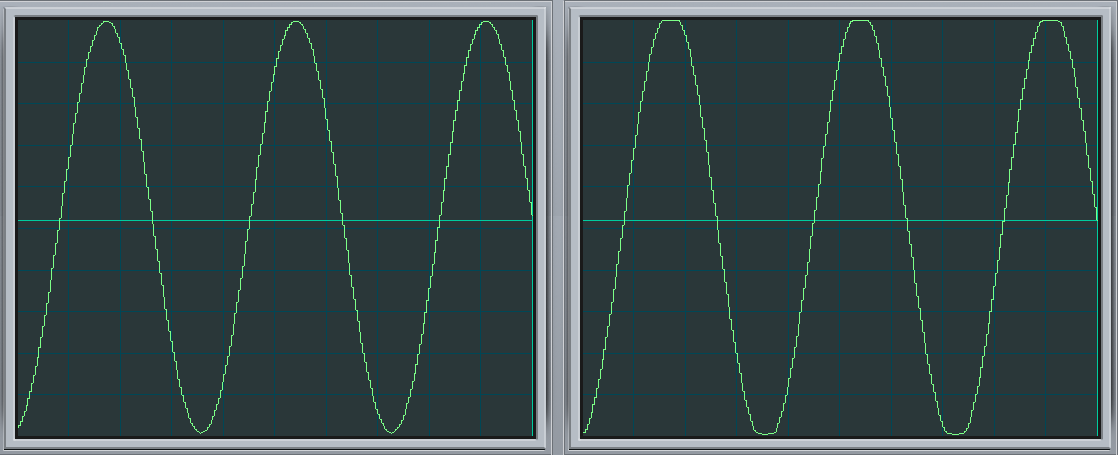

- With Soft Clip off, gain reduction alone prevents the waveform from exceeding the ceiling.

- With Soft Clip on, clipping the peaks supplements the gain reduction process to keep the waveform from exceeding the ceiling (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: The left screen shot shows the waveform with the input 6 dB above the Threshold, and Soft Clip off. The right screen shows the same waveform and levels, but with Soft Clip turned on. Note how the waveform peak is flattened somewhat due to the mild saturation.

While it may sound crazy to want to introduce distortion, in many cases you’ll find you won’t hear the effects of saturation, and you’ll have a hotter output signal.

ENTER THE CEILING

There are two main ways to set the maximum output level:

- With the Threshold set to 0.00, set the maximum output level with the Ceiling control (from 0 to -12 dB).

- With the Ceiling set to 0.00, set the maximum output level with the Threshold control (from 0 to -12 Db).

It’s also possible to set maximum output levels below -12.00 dB. Turn either the Ceiling or Threshold control all the way counter-clockwise to -12.00 dB, then turn down the other control to lower the maximum output level. With both controls fully counter-clockwise, the maximum output level can be as low as -24 dB.

SMOOTHING THE TRANSITION INTO LIMITING

Setting the Ceiling lower than the Threshold is a special case, which allows smoothing the transition into limiting somewhat. Under this condition, the Limiter applies soft-knee compression as the input transitions from below the threshold level to above it.

For example, suppose the Ceiling is 0.00 dB and the Threshold is -6.00 dB. As you turn up the input, you would expect that the output would be the same as the input until the input reaches around -6 dB, at which point the output would be clamped to that level. However in this case, soft-knee compression starts occurring a few dB below -6.00 dB, and the actual limiting to -6.00 dB doesn’t occur until the input is a few dB above -6.00 dB.

The tradeoff for smoothing this transition somewhat is that the Threshold needs to be set below 0.00. In this example, the maximum output is -6.00 dB. If you want to bring it up to 0.00 dB, then you’ll need to add makeup gain using Mixtool module.

Studio One’s Limiter is a highly versatile signal processor, so don’t automatically ignore it in favor of the Compressor or Multiband Dynamics—with some audio material, it could be exactly what you need.

Friday Tips: Frequency-Selective Guitar Compression

Some instruments, when compressed, lack “sparkle” if the stronger, lower frequencies compress high frequencies as well as lower ones. This is a common problem with guitar, but there’s a solution: the Compressor’s internal sidechain can apply compression to only the guitar’s lower frequencies, while leaving the higher frequencies uncompressed so they “ring out” above the compressed sound. (Multiband compression works for this too, but sidechaining can be a faster and easier way to accomplish the same results.) Frequency-selective compression can also be effective with drums, dance mixes, and other applications—like the “pumping drums” effect covered in the Friday Tip for October 5, 2018. Here’s how to do frequency-selective compression with guitar.

- Insert the Compressor in the guitar track.

- Enable the internal sidechain’s Filter button. Do not enable the Sidechain button in the effect’s header.

- Enable the Listen Filter button.

- Turn Lowcut fully counterclockwise (minimum), and set the Highcut control to around 250 – 300 Hz. You want to hear only the guitar’s low frequencies.

- You can’t hear the effects of adjusting the main compression controls (like Ratio and Threshold) while the Listen Filter is enabled, so disable Listen Filter, and start adjusting the controls for the desired amount of low-frequency compression.

- For a reality check, use the Mix control to compare the compressed and uncompressed sounds. The high frequencies should be equally prominent regardless of the Mix control setting (unless you’re hitting the high strings really hard), while the lower strings should sound compressed.

The compression controls are fairly critical in this application, so you’ll probably need to tweak them a bit to obtain the desired results.

If you need more flexibility than the internal filter can provide, there’s a simple workaround.

Copy the guitar track. You won’t be listening to this track, but using it solely as a control track to drive the Compressor sidechain. Insert a Pro EQ in the copied track, adjust the EQ’s range to cover the frequencies you want to compress, and assign the copied track’s output to the Compressor sidechain. Because we’re not using the internal sidechain, click the Sidechain button in the Compressor’s header to enable the external sidechain.

The bottom line is that “compressed” and “lively-sounding” don’t have to be mutually exclusive—try frequency-selective compression, and find out for yourself.

Friday Tips: The Sidechained Spectrum

You’re probably aware that several Studio One audio processors offer sidechaining—Compressor, Autofilter, Gate, Expander, and Channel Strip. However, both the Spectrum Meter and the Pro EQ spectrum meter also have sidechain inputs, which can be very handy. Let’s look at Pro EQ sidechaining first.

When you enable sidechaining, you can feed another track’s output into the Pro EQ’s spectrum analyzer, while still allowing the Pro EQ to modify the track into which it’s inserted. When sidechained, the Spectrum mode switches to FFT curve (the Third Octave and Waterfall options aren’t available). The blue line indicates the level of the signal going through the Pro EQ, while the violet line represents the sidechain signal.

As a practical example of why this is useful, the screen shot shows two drum loops from different drum loop libraries that are used in the same song. The loop feeding the sidechain loop has the desired tonal qualities, so the loop going through the EQ is being matched as closely as possible to the sidechained loop (as shown by a curve that applies more high end, and a slight midrange bump).

Another example would be when overdubbing a vocal at a later session than the original vocal. The vocalist might be off-axis or further away from the mic, which would cause a slight frequency response change. Again, the Pro EQ’s spectrum meter can help point out any differences by comparing the frequency response of the original vocal to the overdub’s response.

The Spectrum Meter

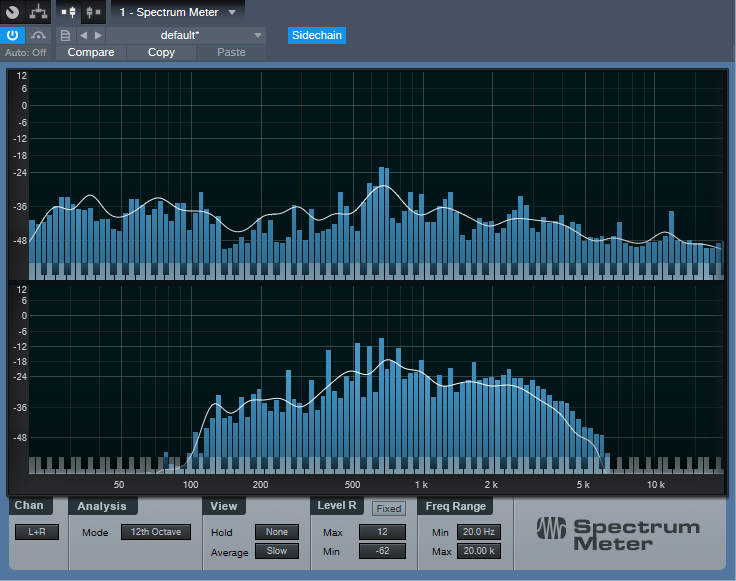

Sidechaining with the Spectrum Meter provides somewhat different capabilities compared to the Pro EQ’s spectrum analyzer.

With sidechain enabled, the top view shows the spectrum of the track into which you’ve inserted the Spectrum Meter. The lower view shows the spectrum of the track feeding the sidechain. When sidechained, all the Spectrum Meter analysis modes are available except for Waterfall and Sonogram.

While useful for comparing individual tracks (as with the Pro EQ spectrum meter), another application is to help identify frequency ranges in a mix that sound overly prominent. Insert the Spectrum Meter in the master bus, and you’ll be able to see if a specific frequency range that sounds more prominent actually is more prominent (in the screen shot, the upper spectrum shows a bump around 600 Hz in the master bus). Now you can send individual tracks that may be causing an anomaly into the Spectrum Metre’s sidechain input to determine which one(s) are contributing the most energy in this region. In the lower part of the screen shot, the culprit turned out to be a guitar part with a wah that emphasized a particular frequency. Cutting the guitar EQ just a little bit around 600 Hz helped even out the mix’s overall sound.

Of course, the primary way to do EQ matching is by ear. However, taking advantage of Studio One’s analysis tools can help speed up the process by identifying specific areas that may need work, after which you can then do any needed tweaking based on what you hear. Although “mixing with your eyes” isn’t the best way to mix, supplementing what you hear with what you see can expedite the mixing process, and help you learn to correlate specific frequencies with what you hear—and there’s nothing wrong with that.

Friday Tips: Synth + Sample Layering

One of my favorite techniques for larger-than-life sounds is layering a synthesizer waveform behind a sampled sound. For example, layering a sine wave along with piano or acoustic guitar, then mixing the sine wave subtly in the background, reinforces the fundamental. With either instrument, this can give a powerful low end. Layering a triangle wave with harp imparts more presence to sampled harps, and layering a triangle wave an octave lower with a female choir sounds like you’ve added a bunch of guys singing along.

Another favorite, which we’ll cover in detail with this week’s tip, is layering a sawtooth or pulse wave with strings. I like those syrupy, synthesized string sounds that were so popular back in the 70s, although I don’t like the lack of realism. On the other hand, sampled strings are realistic, but aren’t lush enough for my tastes. Combine the two, though, and you get lush realism. Here’s how.

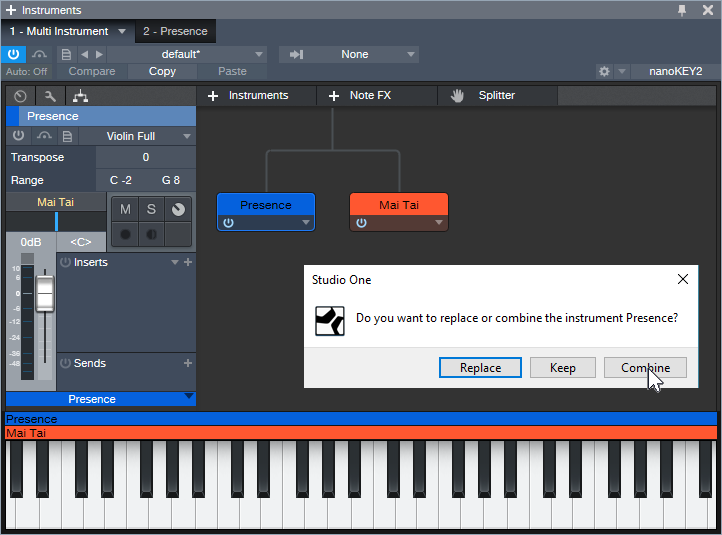

- Create an instrument track with Presence, and call up the Violin Full preset.

- Drag Mai Tai into the same track. You’ll be asked if you want to Replace, Keep, or Combine. Choose Combine.

- After choosing Combine, both instruments will be layered within the Instrument Editor (see above).

- Program Mai Tai for a very basic sound, because it’s there solely to provide reinforcement—a slight detuning of the oscillators, no filter modulation, very basic LFO settings to add a little vibrato and prevent too static a waveform, amplitude envelope and velocity that tracks the Presence sound as closely as possible, some reverb to create a more “concert hall” sound, etc. The screen shot shows the parameters used for this example. The only semi-fancy programming tricks were making one of the oscillators a pulse wave instead of a sawtooth, and panning the two oscillators very slightly off-center.

- Adjust the Mai Tai’s volume for the right mix—enough to supplement Presence, but not overwhelm it.

That’s all there is to it. Listen to the audio example—first you’ll hear only the Presence sound, then the two layers for a lusher, more synthetic vibe that also incorporates some of the realism of sampling. Happy orchestrating!

Friday Tips: Studio One’s Amazing Robot Bassist

When Harmonic Editing was announced, I was interested. When I used it for the first time, I was intrigued. When I discovered what it could do for songwriting…I became addicted.

Everyone creates songs differently, but for me, speed is the priority—I record scratch tracks as fast as possible to capture a song’s essence while it’s hot. But if the tracks aren’t any good, they don’t inspire the songwriting process. Sure, they’ll get replaced with final versions later, but you don’t want boring tracks while writing.

For scratch drums on rock projects, I have a good collection of loops. Guitar is my primary instrument, so the rhythm and lead parts will be at least okay. I also drag the rhythm guitar part up to the Chord Track to create the song’s “chord chart.”

Then things slow down…or at least they did before Harmonic Editing came along. Although I double on keyboards, I’m not as proficient as on guitar but also, prefer keyboard bass over electric bass—because I’ve sampled a ton of basses, I can find the sound I want instantly. And that’s where Harmonic Editing comes in.

The following is going to sound ridiculously easy…because it is. Here’s how to put Studio One’s Robot Bassist to work. This assumes you’ve set the key (use the Key button in the transport, or select an Instrument part and choose Event > Detect Key Signature), and have a Chord Track that defines the song’s chord progression.

- Play the bass part by playing the note on a MIDI keyboard that corresponds to the song’s key. Yes, the note—not notes. For example, if the song is in the key of A, hit an A wherever you want a bass note.

- Quantize what you played. It’s important to quantize because presumably, the chord changes are quantized, and the note attack needs to fall squarely at the beginning of, or within, the chord change. You can always humanize later.

- Open the Inspector, unfold the Follow Chords options, and then choose Bass (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Choose the Bass option to create a bass part when following chords.

- Now you have a bass part! If the bass part works, choose the Edit tab, select all the notes, and choose Action > Freeze Pitch. This is important, because the underlying endless-string-of-notes remains the actual MIDI data. So if you copy the Event and paste it, unless you then ask the pasted clip to follow chords, you have the original boring part instead of the robotized one.

- After freezing, turn off Follow Chords, because you’ve already followed the chords. Now is the time to make any edits. (Asking the followed chords to follow chords can confuse matters, and may modify your edits.)

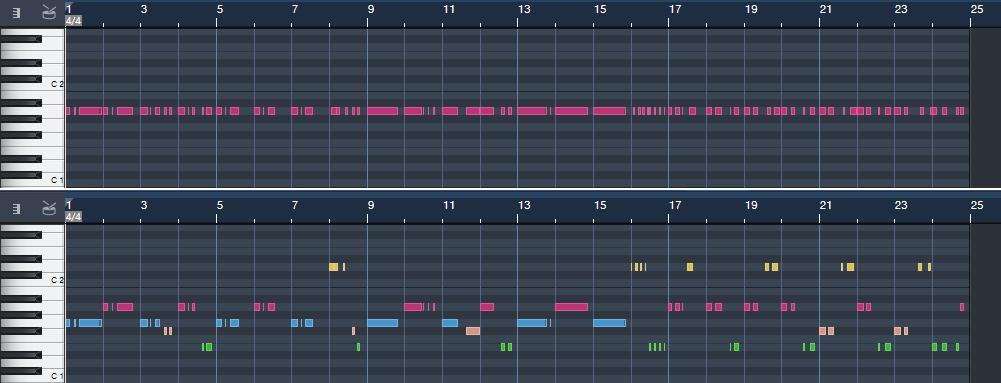

The bottom line: with one take, a few clicks, and (maybe) a couple quick edits—instant bass part (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: The top image is the original part, and yes, it sounds as bad as it looks. The lower image is what happened after it got robotized via Harmonic Editing, and amazingly, it sounds pretty good.

Don’t believe me? Well, listen to the following.

You’ll hear the bass part shown in Fig. 2, which was generated in the early stages of writing my latest music video (I mixed the bass up a little on the demo so you can hear it easily). Note how the part works equally well for the sustained notes toward the beginning, and well as the staccato parts at the end. To hear the final bass part, click the link for Puzzle of Love [https://youtu.be/HgMF-HBMrks]. You’ll hear I didn’t need to do much to tweak what Harmonic Editing did.

But Wait! There’s More!

Not only that, but most of the backing keyboard parts for Puzzle of Love (yes, including the piano intro) were generated in essentially the same way. That requires a somewhat different skill set than robotizing the bass, and a bit more editing. If you want to know more (use the Comments section), we’ll cover Studio One’s Robot Keyboardist in a future Friday Tip.

Friday Tips: Demystifying the Limiter’s Meter Options

Limiters are common mastering tools, so they’re the last processor in a signal chain. Because of this, it’s important to know as much as possible about its output signal, and Studio One’s Limiter offers several metering options.

PkRMS Metering

The four buttons under the meter’s lower left choose the type of meter scale. PkRMS, the traditional metering option, shows the peak level as a horizontal blue bar, with the average (RMS) level as a white line superimposed on the blue bar (Fig. 1). The average level corresponds more closely to how we perceive musical loudness, while the bar indicates peaks, which is helpful when we want to avoid clipping.

The TP Button

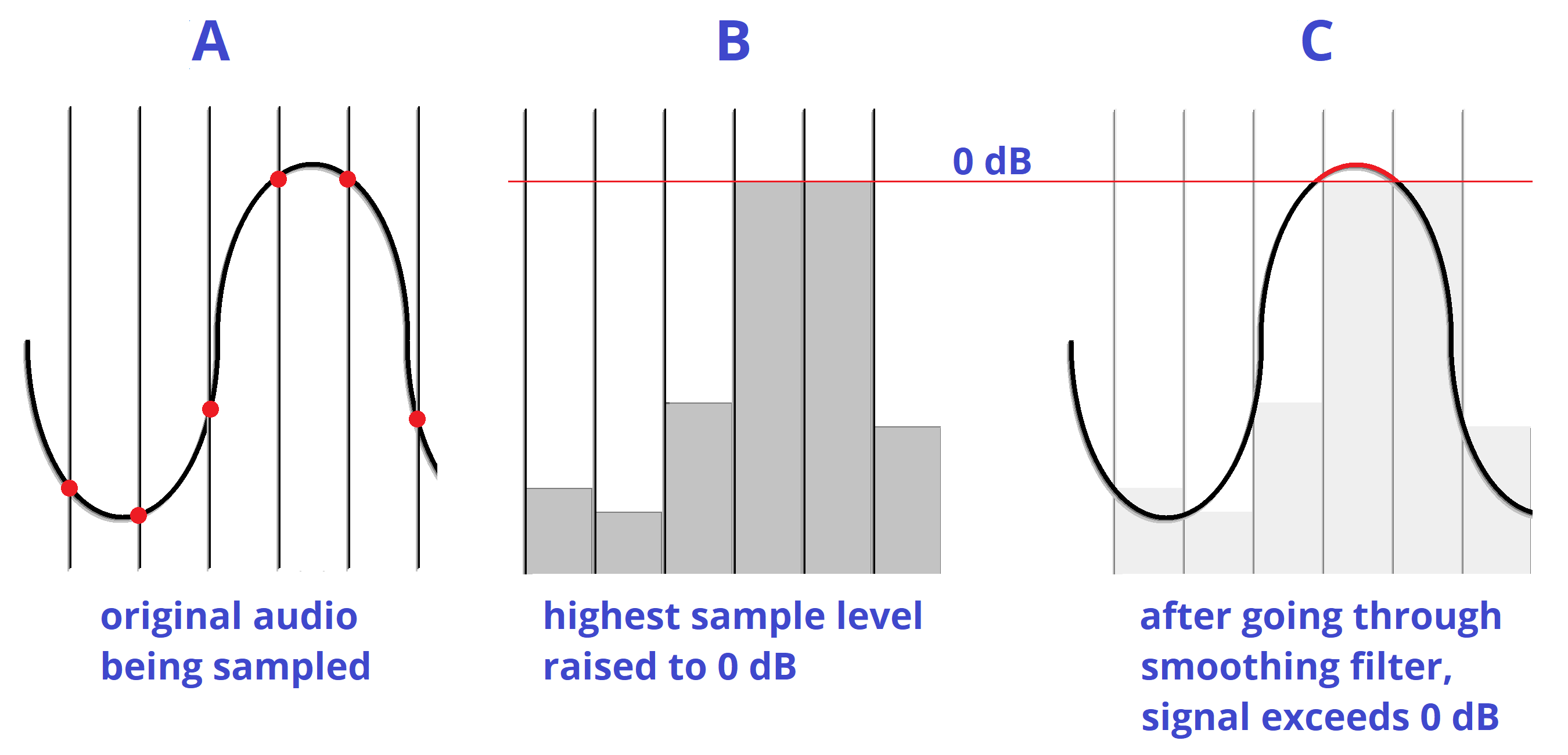

Enabling the True Peak button takes the possibility of intersample distortion into account. This type of distortion can occur on playback if some peaks use up the maximum available headroom in a digital recording, and then these same peaks pass through the digital-to-analog converter’s output smoothing filter to reconstruct the original waveform. This reconstructed waveform might have a higher amplitude than the peak level of the samples, which means the waveform now exceeds the maximum available headroom (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: How intersample distortion occurs.

For example, you might think your audio isn’t clipping because without TP enabled, the output peak meter shows -0.1 dB. However, enabling True Peak metering may reveal that the output is as much as +3 dB over 0 when reconstructed. The difference between standard peak metering and true peak metering depends on the program material.

K-System Metering

The other metering options—K-12, K-14, and K-20 metering—are based on a metering system developed by Bob Katz, a well-respected mastering engineer. One of the issues any mix or mastering engineer has to resolve is how loud to make the output level. This has been complicated by the “loudness wars,” where mixes are intended to be as “hot” as possible, with minimal dynamic range. Mastering engineers have started to push back against this not just to retain musical dynamics, but because hot recordings cause listener fatigue. Among other things, the K-System provides a way to judge a mix’s perceived loudness.

A key K-System feature is an emphasis on average (not just peak) levels, because they correlate more closely to how we perceive loudness. A difference compared to conventional meters is that K-System meters use a linear scale, where each dB occupies the same width (Fig. 3). A logarithmic scale increases the width of each dB as the level gets louder, which although it corresponds more closely to human hearing, is a more ambiguous way to show dynamic range.

Figure 3: The K-14 scale has been selected for the Limiter’s output meter.

Some people question whether the K-System, which was introduced two decades ago, is still relevant. This is because there’s now an international standard (based on a recommendation by the International Telecommunications Union) that defines perceived average levels, based on reference levels expressed in LUFS (Loudness Units referenced to digital Full Scale). As an example of a practical application, when listening to a streaming service, you don’t want massive level changes from one song to the next. The streaming service can regulate the level of the music it receives so that all the songs conform to the same level of perceived loudness. Because of this, there’s no real point in creating a hot master—it will just be turned down to bring it in line with songs that retain dynamic range; and the latter will be turned up if needed to give the same perceived volume.

Nonetheless, the K-System remains valid, particularly when mixing. When you mix, it’s best to have a standardized, consistent monitoring level because human hearing has a different frequency response at different levels (Fig. 4).

Figure 4: The Fletcher-Munson curve shows that different parts of the audio spectrum need to be at different levels to be perceived as having the same volume. Low frequencies have to be substantially louder at lower levels to be perceived as having equal volume.

The K-System links monitoring levels with meter readings, so you can be assured that music reaching the same levels will sound like they’re at the same levels. This requires calibrating your monitor levels to the meter readings with a sound level meter. If you don’t have a sound level meter, many smartphones can run sound level meter apps that are accurate enough.

Note that in the K-System, 0 dB does not represent the maximum possible level. Instead, the 0 dB point is shifted “down” from the top of the scale to either -12, -14, or -20 dB, depending on the scale. These numbers represent the amount of headroom above 0, and therefore, the available dynamic range. You choose a scale based on the music you’re mixing or mastering—like -12 for music with less dynamic range (e.g., dance music), -14 for typical pop music, and -20 dB for acoustic ensembles and classical music. You then aim for having the average level hover around the 0 dB point. Peaks that go above this point will take advantage of the available headroom, while quieter passages will go below this point. Like conventional meters, the K-Systems meters have green, yellow, and red color-coding to indicate levels. Levels above 0 dB trigger the red, but this doesn’t mean there’s clipping—observe the peak meter for that.

Calibrating Your Monitors

The K-System borrows film industry best practices. At 0 dB, your monitors should be putting out 85 dBSPL for stereo material. Therefore, you’ll need a separate calibration for the three scales to make sure that 0 dB on any scale has the same perceived loudness. The simplest way to calibrate is to send pink noise through your system until the chosen K-System meter reads 0 dB (you can download pink noise samples from the web, or use the noise generator in the Mai Tai virtual instrument). Then, using the sound level meter set to C weighting and a slow response, adjust the monitor level for an 85 dB reading. You can put labels next to the level control on the back of your speaker to show the settings that produce the desired output for each K-Scale.

But Wait! There’s More

We’ve discussed the K-System in the context of the Limiter, but if you’re instead using the Compressor or some other dynamics processor that doesn’t have K-System metering, you’re still covered. There’s a separate metering plug-in that shows the K-System scale (Fig. 5).

Figure 5: The Level meter plug-in shows K-System as well as the R128 spec that reads out the levels in LUFS. Enabling TP converts the meter to PkRMS, and shows the True Peak in the two numeric fields.

Finally, the Project Page also includes K-System Metering along with a Spectrum Analyzer, Correlation Meter, and LUFS metering with True Peak (Fig. 6).

Figure 6: The Project Page metering tells you pretty much all you need to need to know what’s going on with your output signal when mastering.

Friday Tip: MIDI Guitar Setup with Studio One

I was never a big fan of MIDI guitar, but that changed when I discovered two guitar-like controllers—the YRG1000 You Rock Guitar and Zivix Jamstik. Admittedly, the YRG1000 looks like it escaped from Guitar Hero to seek a better life, but even my guitar-playing “tubes and Telecasters forever!” compatriots are shocked by how well it works. And Jamstik, although it started as a learn-to-play guitar product for the Mac, can also serve as a MIDI guitar controller. Either one has more consistent tracking than MIDI guitar retrofits, and no detectable latency.

The tradeoff is that they’re not actual guitars, which is why they track well. So, think of them as alternate controllers that take advantage of your guitar-playing muscle memory. If you want a true guitar feel, with attributes like actual string-bending, there are MIDI retrofits like Fishman’s clever TriplePlay, and Roland’s GR-55 guitar synthesizer.

In any case, you’ll want to set up your MIDI guitar for best results in Studio One—here’s how.

Poly vs. Mono Mode

MIDI guitars usually offer Poly or Mono mode operation. With Poly mode, all data played on all strings appears over one MIDI channel. With Mono mode, each string generates data over its own channel—typically channel 1 for the high E, channel 2 for B, channel 3 for G, and so on. Mono mode’s main advantage is you can bend notes on individual strings and not bend other strings. The main advantage of Poly mode is you need only one sound generator instead of a multi-timbral instrument, or a stack of six synths.

In terms of playing, Poly mode works fine for pads and rhythm guitar, while Mono mode is best for solos, or when you want different strings to trigger different sounds (e.g., the bottom two strings trigger bass synths, and the upper four a synth pad). Here’s how to set up for both options in Studio One.

- To add your MIDI guitar controller, choose Studio One > Options > External Devices tab, and then click Add…

- To use your guitar in Mono mode, check Split Channels and make sure All MIDI channels are selected (Fig. 1). This lets you choose individual MIDI channels as Instrument track inputs.

- For Poly mode, you can follow the same procedure as Mono mode but then you may need to select the desired MIDI channel for an Instrument track (although usually the default works anyway). If you’re sure you’re going to be using only Poly mode, don’t check Split Channels, and choose the MIDI channel over which the instrument transmits.

Note that you can change these settings any time in the Options > External Devices dialog box by selecting your controller and choosing Edit.

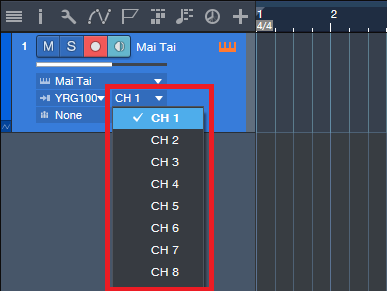

Choose Your Channels

For Poly mode, you probably won’t have to do anything—just start playing. With Mono mode, you’ll need to use a multitimbral synth like SampleTank or Kontakt, or six individual synths. For example, suppose you want to use Mai Tai. Create a Mai Tai Instrument track, choose your MIDI controller, and then choose one of the six MIDI channels (Fig. 2). If Split Channels wasn’t selected, you won’t see an option to choose the MIDI channel.

Figure 2: If you chose Split Channels when you added your controller, you’ll be able to assign your instrument’s MIDI input to a particular MIDI channel.

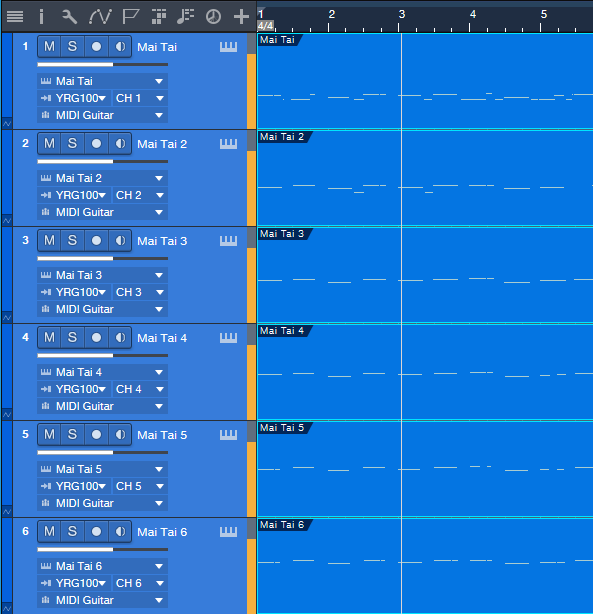

Next, after choosing the desired Mai Tai sound, duplicate the Instrument track five more times, and choose the correct MIDI channel for each string. I like to Group the tracks because this simplifies removing layers, turning off record enable, and quantizing. Now record-enable all tracks, and start recording. Fig. 3 shows a recorded Mono guitar part—note how each string’s notes are in their own channel.

Figure 3: A MIDI guitar part that was recorded in Mono mode is playing back each string’s notes through its own Mai Tai synthesizer.

To close out, here are three more MIDI guitar tips.

- In Mono mode with Mai Tai (or whatever synth you use), set the number of Voices to 1 for two reasons. First, this is how a real guitar works—you can play only one note at a time on a string. Second, this will often improve tracking in MIDI guitars that are picky about your picking.

- Use a synth’s Legato mode, if available. This will prevent re-triggering on each note when sliding up and down the neck, or doing hammer-ons.

- The Edit view is wonderful for Mono mode because you can see what all six strings are playing, while editing only one.

MIDI guitar got a bad rap when it first came out, and not without reason. But the technology continues to improve, dedicated controllers overcome some of the limitations of retrofitting a standard guitar, and if you set up Studio One properly, MIDI guitar can open up voicings that are difficult to obtain with keyboards.

In Mono mode with Mai Tai (or whatever synth you use), set the number of Voices to 1 for two reasons. First, this is how a real guitar works—you can play only one note at a time on a string. Second, this will often improve tracking in MIDI guitars that are picky about your picking.

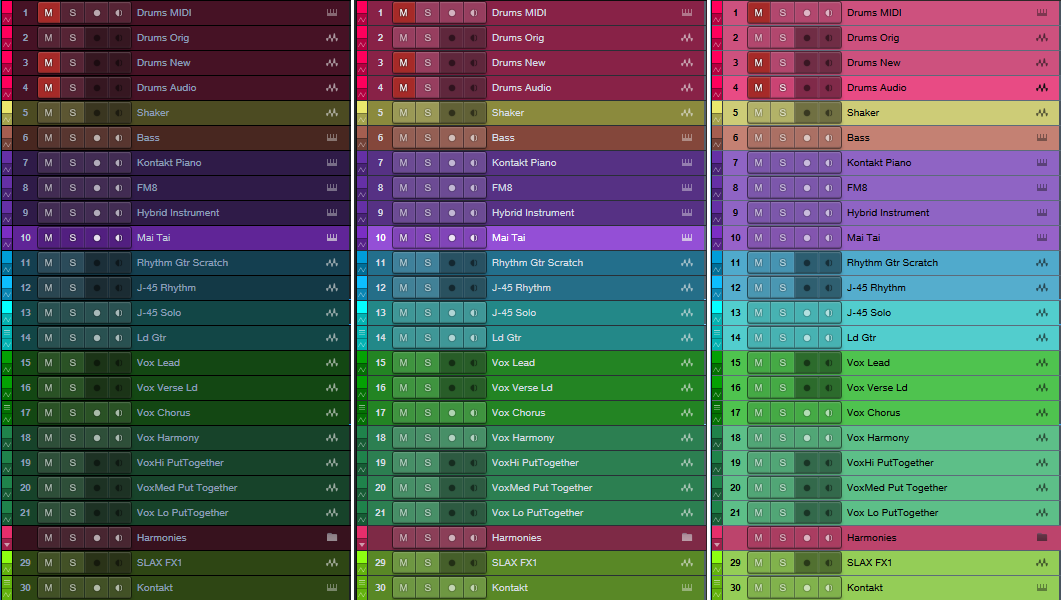

Friday Tip: Colorization: It’s Not Just About Eye Candy

Some people think colorization is frivolous—but I don’t. I started using colorization when writing articles, because it was easy to identify elements in the illustrations (e.g., “the white audio is the unprocessed sound, the blue audio is compressed”). But the more I used colorization, the more I realized how useful it could be.

Customizing the “Dark” and “Light” Looks

Although a program’s look is usually personal preference, sometimes it’s utilitarian. When working in a video suite, the ambient lighting is often low, so that the eye’s persistence of vision doesn’t influence how you perceive the video. For this situation, a dark view is preferable. Conversely, those with weak or failing vision need a bright look. If you’re new to Studio One, you might want the labels to really “pop” but later on, as you become more familiar with the program, darken them somewhat. You may want a brighter look when working during daytime, and a more muted look at night. Fortunately, you can save presets for various looks, and call up the right look for the right conditions (although note that there are no keyboard shortcuts for choosing color presets).

You’ll find these edits under Options > General > Appearance. For a dark look, move the Background Luminance slider to the left and for a light look, to the right (Fig. 1). I like -50% for dark, and +1 for light. For the dark look, setting the Background Contrast at -100% means that the lettering won’t jump out at you. For the brightest possible look, bump the Background Contrast to 100% so that the lettering is clearly visible against the other light colors, and set Saturation to 100% to brighten the colors. Conversely, to tone down the light look, set Background Contrast and Saturation to 0%.

Hue Shift customizes the background of menu bars, empty fields that are normally gray, and the like. The higher the Saturation slider, the more pronounced the colorization.

The Arrangement sliders control the Arrangement and Edit view backgrounds (i.e., what’s behind the Events). I like to see the vertical lines in the Arrangement view, but also keep the background dark. So Arrangement Contrast is at 100%, and Luminance is the darkest possible value (around 10%) that still makes it easy to see horizontal lines in the Edit view (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: The view on the left uses 13% luminance and 100% contrast to make the horizontal background lines more pronounced.

Streamlining Workflow with Color

With a song containing dozens of tracks, it can be difficult to identify which Console channel strip controls which instrument, particularly with the Narrow console view. The text at the bottom of each channel strip helps, but you often need to rename tracks to fit in the allotted space. Even then, the way the brain works, it’s easier to identify based on color (as deciphered by your right brain) than text (as deciphered by your left brain). Without getting too much into how the brain’s hemispheres work, the right brain is associated more with creative tasks like making music, so you want to stay in that mode as much as possible; switching between the two hemispheres can interrupt the creative flow.

I’ve developed standard color schemes for various types of projects. Of course, choose whatever colors work for you; for example, if you’re doing orchestral work, you’d have a different roster of instruments and colors. With my scheme for rock/pop, lead instruments use a brighter version of a color (e.g., lead guitar bright blue, rhythm guitar dark blue).

- Main drums – red

- Percussion – yellow

- Bass – brown

- Guitar – blue

- Voice – green

- Keyboards and orchestral – purple

- FX – lime green

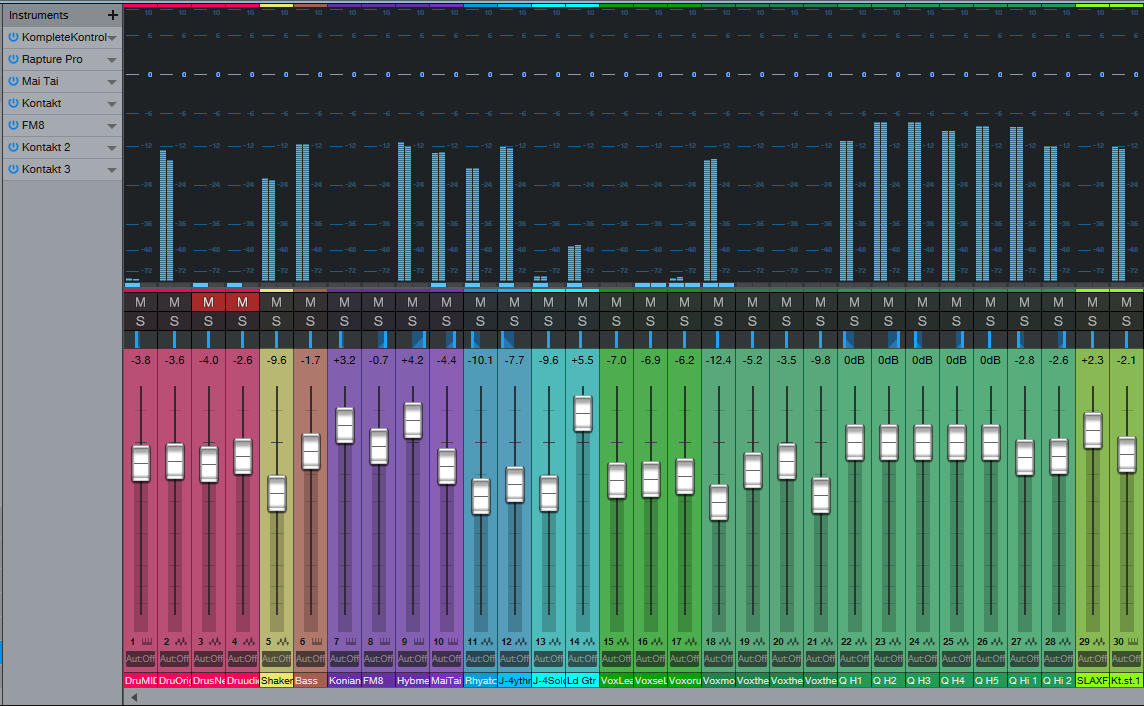

Furthermore, similar instruments are grouped together in the mixer. So for vocals, you’ll see a block of green strips, for guitar a block of blue strips, etc. (Fig. 3)

Figure 3: A colorized console, with a bright look. The colorization makes it easy to see which faders control which instruments.

To colorize channel strips, choose Options > Advanced tab > Console tab (or click the Console’s wrench icon) and check “Colorize Channel Strips.” This colorizes the entire strip. However, if you find colorized strips too distracting, the name labels at the bottom (and the waveforms in the arrange view) are always colored according to your choices. Still, when the Console faders are extended to a higher-than-usual height, I find it easier to grab the correct fader with colored console strips.

In the Arrange view, you can colorize the track controls as well—click on the wrench icon, and click on “Colorize Track Controls.” Although sometimes this feels like too much color, nonetheless, it makes identifying tracks easier (especially with the track height set to a narrow height, like Overview).

Color isn’t really a trivial subject, once you get into it. It has helped my workflow, so I hope these tips serve you as well.

Extra TIP: Buy Craig Anderton’s Studio One eBook here for only $10 USD!

Friday Tips: The Melodyne Envelope Flanger

This isn’t a joke—there really is an envelope-controlled flanger hidden inside Melodyne Essential that sounds particularly good with drums, but also works well with program material. The flanging is not your basic, boring “whoosh-whoosh-whoosh” LFO-driven flanging, but follows the amplitude envelope of the track being flanged. It’s all done with Melodyne Essential, although of course you can also do this with more advanced Melodyne versions. Here’s how simple it is to do envelope-followed flanging in Studio One.

- Duplicate the track or Event you want to flange.

- Select the copied Event, then type Ctrl+M (or right-click on the Event and choose Edit with Melodyne)

- In Melodyne, under Algorithm, choose Percussive and let Melodyne re-detect the pitches.

- “Select all” in Melodyne so that all the blobs are red, then start playback.

- Click in the “Pitch deviation (in cents) of selected note” field.

- Drag up or down a few cents to introduce flanging. I tend to like dragging down about -14 cents.

As with any flanging effect, you can regulate the mix of the flanged and dry sounds by altering the balance of the two tracks.

Note that altering the Pitch Deviation parameter indicates an offset from the current Pitch Deviation, not an absolute value. For example if you drag down to -10 cents, release the mouse button, and click on the parameter again, the display will show 0 instead of -10. So if you drag up by +4 cents, the pitch deviation will now be at -6 cents, not +4. If you get too lost, just select all the blobs, choose the Percussion algorithm again, and Melodyne will set everything back to 0 cents after re-detecting the blobs.

And of course, I don’t expect you to believe that something this seemingly odd actually works, so check out the audio example. The first part is envelope-flanged drums, and the second part applies envelope flanging to program material from my [shameless plug] Joie de Vivre album. So next time you need envelope-controlled flanging, don’t reach for a stompbox—edit with Melodyne.

Friday Tips: Studio One’s Hybrid Reverb

The previous tip on creating a dual-band reverb generated a fair amount of interest, so let’s do one more reverb-oriented tip before moving on to another topic.

Studio One has three different reverbs—Mixverb, Room Reverb, and OpenAIR—all of which have different attributes and personalities. I particularly like the Room Reverb for its sophisticated early reflections engine, and the OpenAIR’s wide selection of decay impulses (as well as the ability to load custom impulses I’ve made).

Until now, it never occurred to me how easy it is to create a “hybrid” reverb with the best of both worlds: using the Room Reverb solely as an early reflections engine, and the OpenAIR solely for the reverb decay. To review, reverb is a continuum—it starts with silence during the pre-delay phase when the sound first travels to hit a room’s surfaces, then morphs into early reflections as these sounds bounce around and create echoes, and finally, transforms into the reverb decay—the most complex component. Each one of these components affects the sound differently. In Studio One, these components don’t all have to be from the same reverb.

THE EARLY REFLECTIONS ENGINE

Start by inserting the Room Reverb into an FX Channel, and calling up the Default preset. Then set the Reverb Mix to 0.00 and the Dry/Wet Mix to 100%. The early reflections appear as discrete vertical lines. They’re outlined in red in the screen shot below.

If you haven’t experimented with using the Room Reverb as a reflections engine, before proceeding now would be a good time to use the following evaluation procedure and familiarize yourself with its talents.

- From the Browser, load the loop Crowish Acoustic Chorus 1.wav (Loops > Rock > Drums > Acoustic) into a stereo track. This loop is excellent for showcasing the effects of early reflections.

- Create a pre-fader send from this track to the FX Channel with the Room Reverb, and bring the drum channel fader all the way down for now so you hear only the effects of the Room Reverb.

- Let’s look at the Room parameters. Vary the Size parameter. The bigger the room, the further away the reflections, and the quieter they are.

- Set the Size to around 3.00. Vary Height. Note how at maximum height, the sound is more open; at minimum height, the sound is more constricted. Leave Height around 1.00.

- Now vary Width. With narrower widths, you can really hear that the early reflections are discrete echoes. As you increase width, the reflections blend together more. Leave Width around 2.00.

- The Geometry controls might as well be called the “stand here” controls. Turning up Distance moves you further away from the sound source. Asy varies your position in the left-right direction within the room.

- Plane is a fairly subtle effect. To hear what it does, repeat steps 3 and 4, and then set Size to around 3.00, Dist to 0.10, and Asy to 1.00. Plane spreads the sounds a bit more apart at the maximum setting.

Now that you know how to set up different early reflections sounds, let’s create the other half of our hybrid reverb.

THE REVERB DECAY

To provide the reverb decay, insert the OpenAIR reverb after the Room Reverb. Whenever you call up a new OpenAIR preset, do the following.

- Set ER/LR to 1.00.

- Set Predelay to minimum (-150.00 ms).

- Initially set Envelope Fade-in and Envelope ER/LR-Xover to 0.00 ms.

There are two ways to make a space for the early reflections so that they occur before the reverb tail: set an Envelope Fade-in time, an Envelope ER/LR-Xover time, or both. Because the ER/LR control is set to 1.00 there are no early reflections in the Open AIR preset, so if you set the ER/LR-Xover time to (for example) 25 ms, that basically acts like a 25 ms pre-delay for the reverb decay. This opens up a space for you to hear the early reflections before the reverb decay kicks in. If you prefer a smoother transition into the decay, increase the Envelope Fade-in time, or combine it with some ER/LR-Xover time to create a pre-delay along with a fade-in.

The OpenAIR Mix control sets the balance of the early reflections contributed by the Room Reverb and the longer decay tail contributed by the OpenAIR reverb. Choose 0% for reflections only, 100% for decay only.

…AND BEYOND

There are other advantages of the hybrid reverb approach. In the OpenAIR, you can include its early reflections to supplement the ones contributed by the Room Reverb. When you call up a new preset, instead of setting the ER/LR, Predelay, Envelope Fade-In, and Envelope ER/LR-Xover to the defaults mentioned above, bypass the Room Reverb and set the Open AIR’s early reflections as desired. Then, enable the Room Reverb to add its early reflections, and tweak as necessary.

It does take a little effort to edit your sound to perfection, so save it as an FX Chain and you’ll have it any time you want it.