Category Archives: Studio One

Friday Tips—Blues Harmonica FX Chain

If you’ve heard blues harmonica greats like Junior Wells, James Cotton, Jimmy Reed, and Paul Butterfield, you know there’s nothing quite like that big, brash sound. They all manage to transform the harmonica’s reedy timbre into something that seems more like a member of the horn family.

To find out more about the techniques of blues harmonica, check out the article Rediscovering Blues Harmonica. It covers why you don’t play blues harp in its default key (e.g., you typically use a harmonica in the key of A for songs in E), how to mic a harmonica, and more. However, the secret to that big sound is playing through the distortion provided by an amp, or in our software-based world, an amp sim. I don’t really find the Ampire amps suitable for this application, but we can put together an FX Chain that does the job.

Check out the demo to hear the desired goal. The first 12 bars are unprocessed harmonica (other than limiting). The second 12 bars use the FX Chain described in this week’s tip, and which you can download for your own use.

The chain starts with a Limiter to provide a more sustained, consistent sound.

Next up: A Pro EQ to take out all the lows and highs, which tightens up the sound and reduces intermodulation distortion. (When using an amp sim, blues harmonica is also a good candidate for multiband processing, as described in the February 1 Friday Tip.)

Now it’s time for the Redlight Dist to provide the distortion. For the cabinet, this FX Chain uses the Ampire solely for its 4 x 10 American cabinet—no amp or stomps.

After the distortion/cabinet combo, a little midrange “honk” makes the harmonica stand out more in the mix.

For a final touch, blues harp often plays through an amp with reverb—so a good spring reverb effect adds a vintage vibe.

You can download the Blues Harp.multipreset and use it as it, but I encourage playing around with it—try different types of distortion and amps, mess with the EQ a bit, and so on. For an example of a finished song with amp sim blues harmonica in context, check out I’ll Take You Higher on YouTube.

Click here to download the multipreset!

Friday Tips—Studio One Meets Vinyl

Although vinyl represents a tiny fraction of the media people use to listen to music, you, or a client, may want to do a vinyl release someday. Conventional wisdom is split between “you don’t dare master for vinyl” and “sure, you can master for vinyl if you know certain rules.”

Both miss the point that the engineer using the lathe to do the cutting will make the ultimate decisions. You can provide something mastered for CD, and the engineer will do what’s possible to make it vinyl-friendly—but then the vinyl version may sound very different from the CD, because of the compromises needed to accommodate vinyl. Conversely, you can “prep for vinyl” and if you do a good job, the engineer running the cutting lathe will have an easier time, and there won’t be as much difference between the vinyl and CD release.

But before going any further, let’s explore why vinyl is different.

TRADEOFFS

A stylus moves side to side, and up and down, to create stereo. Louder levels mean wide and deeper grooves; if too loud, the needle can jump out of the groove. Lower frequencies hog “groove space” more than high frequencies, but also, a stylus has a difficult time moving fast enough to track high frequencies, which leads to distortion.

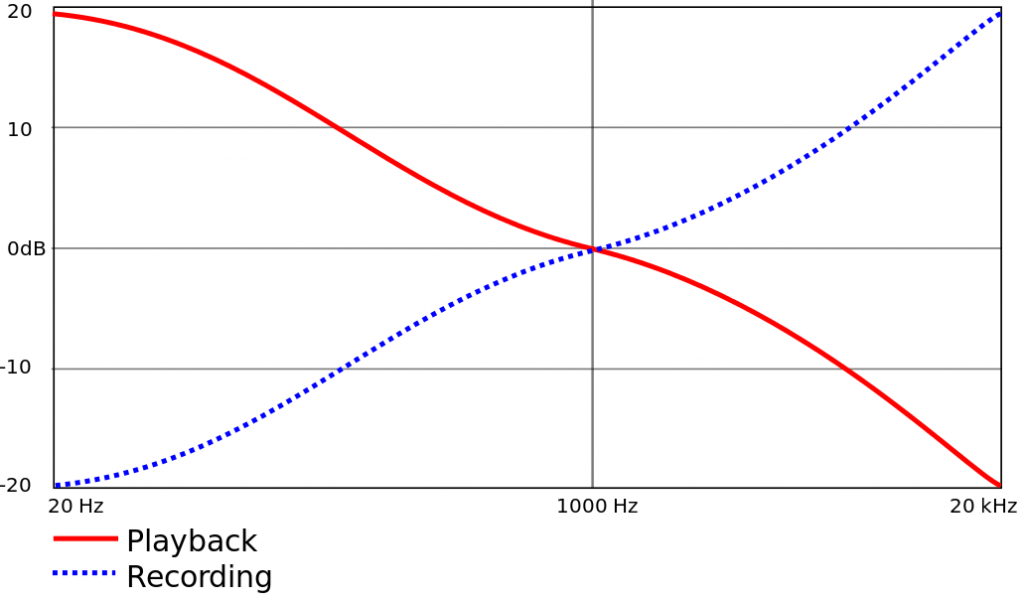

To compensate, the RIAA initiated an EQ curve that cuts bass up to -20 dB at low frequencies before the audio gets turned into a master lacquer, and boosts highs by an equally dramatic amount to help overcome surface noise. On playback, an inverse curve boosts the bass to restore its original level; cutting highs restores the proper high-frequency balance to reduce surface noise and encourage better tracking (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: RIAA equalization record and playback curves for vinyl records.

PREPARATION IN THE SONG PAGE

There are four main ways to make more vinyl-friendly mixes in the Song Page.

- Avoid excessive high frequencies. Use de-essing on vocals, but de-essing can also tame distorted guitar, cymbals, and other high-frequency sound sources (Fig. 2). Excess sibilance or brightness translates to splattering distortion with vinyl.

Figure 2: Studio One’s compressor can do de-essing and other frequency-selective compression.

- Trim the lows and highs, as appropriate for the program material. Use a 48 dB/octave Pro EQ LC filter to cut everything below 20 to 40 Hz. Back in the vinyl days, sharp cuts above 15 kHz or even 10 kHz were also the norm (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: Sharp LC and HC filters trim out vinyl-hostile frequencies.

- Center the bass. The worst-case audio for a stylus to track is out-of-phase bass in the left and right channels. Besides, low frequencies aren’t very directional, so any stereo is more or less pointless unless you’re listening on headphones. The easiest way to center bass in Studio One is to place a Splitter in the master bus, and split by frequency. There is no “rule” for the correct crossover frequency; too low, and potentially problematic frequencies can get through. Too high, and you’ll start interfering with the lower end of guitar and other instruments. That said, 70 to 170 Hz is a good place to start. Then, follow that low split with the Dual Pan, and center both channels (Fig. 4). Also consider avoiding hard left/right panning for lower-frequency instruments, like toms.

Figure 4: Using a Splitter as a crossover, with a Dual Pan, can center low frequencies in the stereo spread.

- Check your mix in mono. Phase issues, whether accidental or deliberate (i.e., psycho-acoustic processors) can really mess with the cutting lathe. Use Studio One’s Correlation meter to confirm there aren’t major phase issues (see the Friday Tip for September 28, 2018).

PREPARATION IN THE PROJECT PAGE

You can take matters only so far in the Project Page before taking your mixes to a mastering engineer who knows how to prep for, and cut, vinyl. But there are steps you should take to assist the process of creating a vinyl-friendly master for duplication.

- Follow the rules for album length. The two sides should be of approximately equal length, and for a 12” record, should not exceed 20 minutes. Longer sides mean narrower grooves, lower levels, and more issues with surface noise. There’s a reason why many classic albums were 30-40 minutes long total.

- Follow the rules for album order. Fidelity deteriorates as the stylus works its way toward the inner grooves. Place your loudest songs, with the most complex spectra, at the beginning of a side, and the quieter songs toward the end. This may require choosing whether you want to compromise your art, or the sound quality.

- Don’t try to win the loudness wars. You can ask the engineer cutting the vinyl to put as loud a level as possible on vinyl, but don’t try it yourself. Loud, distorted or partially clipped audio only sounds worse when translated to vinyl because the stylus can’t follow clipped waveforms easily. Think about it—a mechanical object can’t snap to a maximum value and then back down to a lower value instantly. What matters is the average, not peak, level; I master to around -10 or -11 LUFS these days, and that works for vinyl. You can maybe stretch that to -8 with some material, but the louder you go, the greater the chance of distortion.

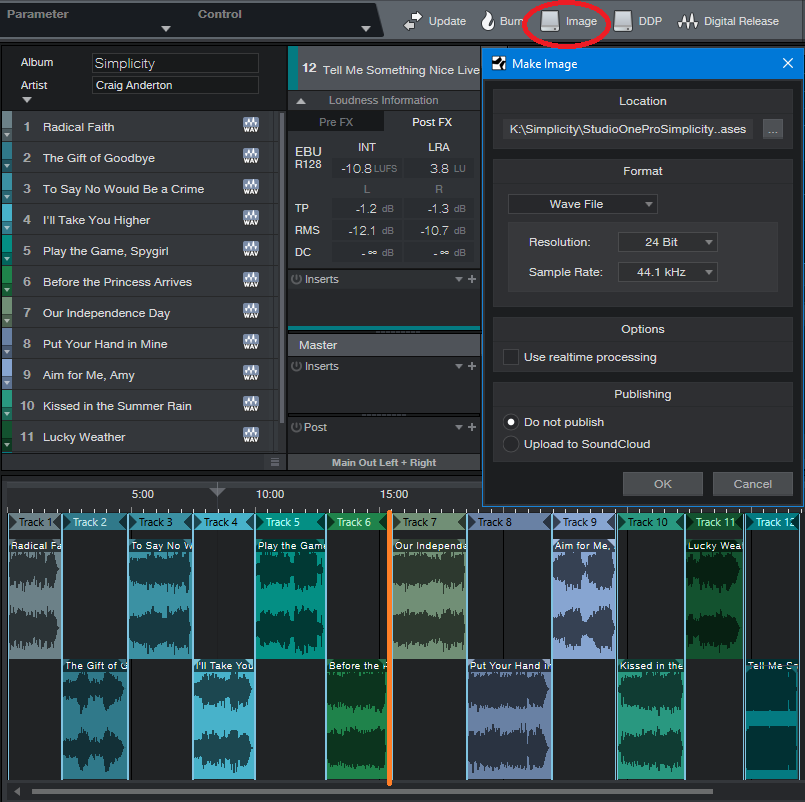

- Create a complete, continuous disc image file (Fig. 5) that represents exactly what you want each side to sound like. The process of transferring from a final mix to a cutting lathe is done in real time. The image should include the desired silence between cuts, crossfades, and song order. Of course you can have a mastering engineer assemble the album from individual cuts, but you’ll pay extra.

Figure 5: I mastered my 2017 album project, Simplicity, with vinyl in mind “just in case.” The total length is about 31 minutes, and the project splits into two sides of almost equal length between songs 6 and 7 (shown with an orange line). An image of the entire project is about to be created.

- Get a reference lacquer. You’ll pay extra for this, but it lets you “proof” the settings the mastering engineer uses to create the final master lacquer. You can play the reference at least a dozen or more times before the quality starts to deteriorate audibly. If changes need to be made, the mastering engineer will have written down the settings used to make the reference, and re-adjust them as needed.

SO THAT’S WHY VINYL SOUNDS BETTER!!

Yes. Properly mastered vinyl releases didn’t have harsh high frequencies, they had dynamic range because you couldn’t limit the crap out of them without having them sound distorted, and the bass coalesced around the stereo image’s center, where it belongs. In fact, if you master with vinyl in mind, you just might find that those masters make CDs sound a whole lot better as well!

Friday Tips: Multiband Processing Development System

I’m a big fan of multiband processing. This technique divides a signal into bands (I generally choose lows, low mids, mids, and high mids), processes each band independently, then sums the bands’ outputs back together again.

I first used multiband processing in the early 80s, with the Quadrafuzz distortion unit (later virtualized by both Steinberg and MOTU). This produces a “cleaner” distortion sound because you didn’t have the intermodulation distortion caused by low strings and high strings interacting with each other. However, multiband processing is also useful with delay, like using shorter delays on lower frequencies, and longer delays on higher frequencies…or chorus, if you want a super-lush sound. But there are other cool surprises, like using different effects in the different bands, or using envelope filters.

So for Studio One, I’ve created a multiband processing “development system” for creating new multiband effects—and that’s the subject of this tip.When I find an effect I like, it gets turned into a fixed FX chain that uses the Splitter module’s multi-band capabilities instead of buses to create four parallel signal paths.

Band Splitting

Figure 1: The Multiband Processing Development System, set to evaluate multiband processing with analog delay.

Start by creating four pre-fader sends to feed four buses (fig. 1). Each bus handles a specific frequency range. The simplest way to create splits is with the Multiband Dynamics set to no compression, so it can serve as a crossover.

To create the bands, insert a Multiband Dynamics processor in one of the buses, open it, and set the compression Ratio for all Multiband Dynamics bands to 1:1. This prevents any compression from occurring.

Referring to fig. 2, as you play your instrument (or other signal source you want to process), solo the Low band. Then adjust the Low / Low-Mid X-Over Frequency control to set the dividing frequency between the low- and low-mid band.

Next, solo the Low Mid band and adjust its frequency control. Use a similar procedure on each band until you’ve chosen the frequencies you want each band to cover. For guitar, having more than four bands isn’t all that necessary, so I normally set the frequency splits to around 250 Hz, 500 Hz, and 1 kHz. The resulting bands are:

- Below 250 Hz

- 250 – 500 Hz

- 500 – 1,000 Hz

- Above 1,000 Hz

Setting the Mid-High / High X-Over Frequency to Max essentially removes the Multiband Dynamics’ top band.

After choosing the frequency bands, copy the Multiband Dynamics processor to the other three buses. Solo the Low band for one bus, the Low Mid in the next bus, the Mid in the next bus, and finally, the High Mids in the fourth bus. Now each bus covers its assigned frequency range.

At this point, all that’s left is to insert your processor(s) of choice into each band. Don’t forget that you can experiment with panning the different bands, changing levels, altering sends to the buses to affect distortion drive, and more. This type of setup allows for a ton of options…so get creative!

Friday Tip: MIDI Guitar Setup with Studio One

I was never a big fan of MIDI guitar, but that changed when I discovered two guitar-like controllers—the YRG1000 You Rock Guitar and Zivix Jamstik. Admittedly, the YRG1000 looks like it escaped from Guitar Hero to seek a better life, but even my guitar-playing “tubes and Telecasters forever!” compatriots are shocked by how well it works. And Jamstik, although it started as a learn-to-play guitar product for the Mac, can also serve as a MIDI guitar controller. Either one has more consistent tracking than MIDI guitar retrofits, and no detectable latency.

The tradeoff is that they’re not actual guitars, which is why they track well. So, think of them as alternate controllers that take advantage of your guitar-playing muscle memory. If you want a true guitar feel, with attributes like actual string-bending, there are MIDI retrofits like Fishman’s clever TriplePlay, and Roland’s GR-55 guitar synthesizer.

In any case, you’ll want to set up your MIDI guitar for best results in Studio One—here’s how.

Poly vs. Mono Mode

MIDI guitars usually offer Poly or Mono mode operation. With Poly mode, all data played on all strings appears over one MIDI channel. With Mono mode, each string generates data over its own channel—typically channel 1 for the high E, channel 2 for B, channel 3 for G, and so on. Mono mode’s main advantage is you can bend notes on individual strings and not bend other strings. The main advantage of Poly mode is you need only one sound generator instead of a multi-timbral instrument, or a stack of six synths.

In terms of playing, Poly mode works fine for pads and rhythm guitar, while Mono mode is best for solos, or when you want different strings to trigger different sounds (e.g., the bottom two strings trigger bass synths, and the upper four a synth pad). Here’s how to set up for both options in Studio One.

- To add your MIDI guitar controller, choose Studio One > Options > External Devices tab, and then click Add…

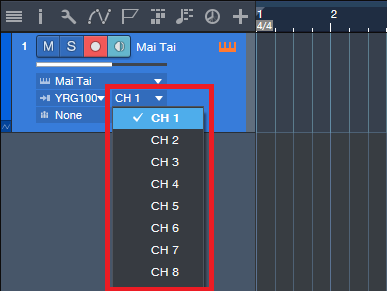

- To use your guitar in Mono mode, check Split Channels and make sure All MIDI channels are selected (Fig. 1). This lets you choose individual MIDI channels as Instrument track inputs.

- For Poly mode, you can follow the same procedure as Mono mode but then you may need to select the desired MIDI channel for an Instrument track (although usually the default works anyway). If you’re sure you’re going to be using only Poly mode, don’t check Split Channels, and choose the MIDI channel over which the instrument transmits.

Note that you can change these settings any time in the Options > External Devices dialog box by selecting your controller and choosing Edit.

Choose Your Channels

For Poly mode, you probably won’t have to do anything—just start playing. With Mono mode, you’ll need to use a multitimbral synth like SampleTank or Kontakt, or six individual synths. For example, suppose you want to use Mai Tai. Create a Mai Tai Instrument track, choose your MIDI controller, and then choose one of the six MIDI channels (Fig. 2). If Split Channels wasn’t selected, you won’t see an option to choose the MIDI channel.

Figure 2: If you chose Split Channels when you added your controller, you’ll be able to assign your instrument’s MIDI input to a particular MIDI channel.

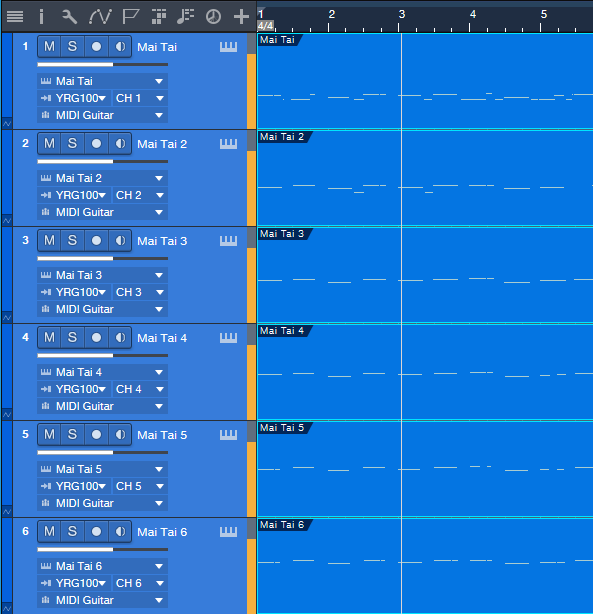

Next, after choosing the desired Mai Tai sound, duplicate the Instrument track five more times, and choose the correct MIDI channel for each string. I like to Group the tracks because this simplifies removing layers, turning off record enable, and quantizing. Now record-enable all tracks, and start recording. Fig. 3 shows a recorded Mono guitar part—note how each string’s notes are in their own channel.

Figure 3: A MIDI guitar part that was recorded in Mono mode is playing back each string’s notes through its own Mai Tai synthesizer.

To close out, here are three more MIDI guitar tips.

- In Mono mode with Mai Tai (or whatever synth you use), set the number of Voices to 1 for two reasons. First, this is how a real guitar works—you can play only one note at a time on a string. Second, this will often improve tracking in MIDI guitars that are picky about your picking.

- Use a synth’s Legato mode, if available. This will prevent re-triggering on each note when sliding up and down the neck, or doing hammer-ons.

- The Edit view is wonderful for Mono mode because you can see what all six strings are playing, while editing only one.

MIDI guitar got a bad rap when it first came out, and not without reason. But the technology continues to improve, dedicated controllers overcome some of the limitations of retrofitting a standard guitar, and if you set up Studio One properly, MIDI guitar can open up voicings that are difficult to obtain with keyboards.

In Mono mode with Mai Tai (or whatever synth you use), set the number of Voices to 1 for two reasons. First, this is how a real guitar works—you can play only one note at a time on a string. Second, this will often improve tracking in MIDI guitars that are picky about your picking.

Studio One 4.1.3 is here!

Studio One 4.1.3 is a free maintenance update for all Studio One 4 users and includes a variety of improvements. Click “Check for Updates” in Studio One’s Start Page to get it!

- Support for new Studio Series USB-C™-compatible Interfaces

- FX Sends are now visible by default on the console

Please click here to check out the latest release notes for a full list of fixes and improvements. in 4.1.3

In case you missed it, this release is hot on the heels of 4.1.2, which included the following:

- AAF Import/Export now supports volume automation

- AAF Export is now compatible with MOTU Digital Performer 9 (using legacy mode)

- A safety query has been added to the “Reset recent songs list” function

- Saving versions of a song is now more flexible with added control over how they affect the original song

- The song key signature is now included in the song meta data

- Quantize macros have been updated

- Multi-touch support now prevents “Mouse-as-Pointer” emulation for Plug-ins

- Time-stretching events in Arrangement is now reflected in the Audio Editor

Please click here to check out the latest release notes for a full list of fixes and improvements in 4.1.2.

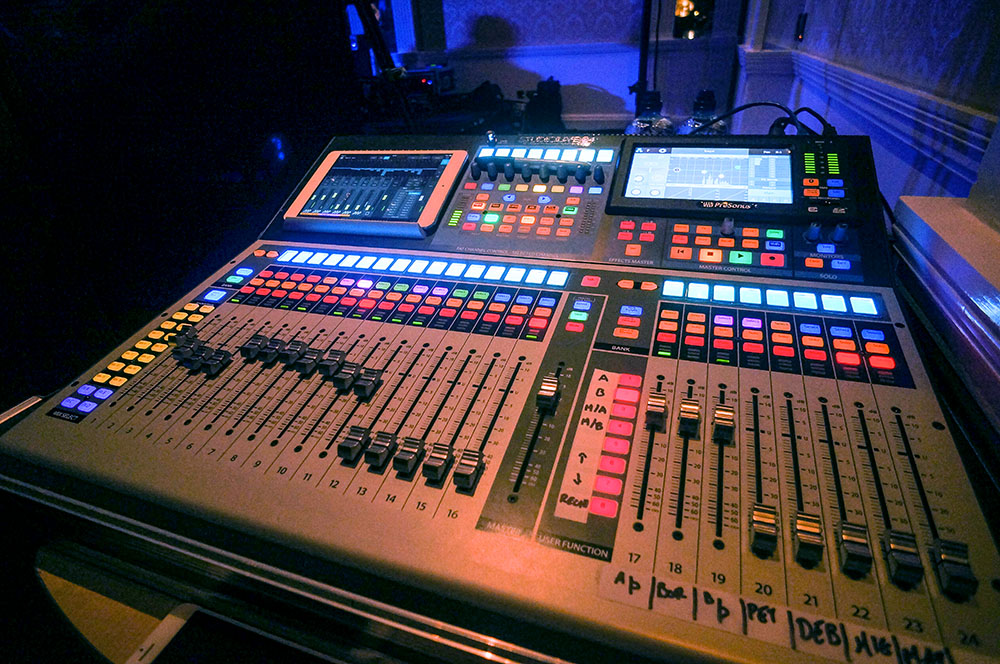

The Bentley Boys on StudioLive

The Bentley Boys

The Bentley Boys are Ireland’s premier corporate entertainment and wedding band. They were voted RSVP Wedding Band of the Year in 2013 and 2014 and Nominated Weddings Online Band of the Year for 2013, 2014 & 2015, 2016 and 2017. The Bentley Boys play all around Ireland and they tailor the band to every event to make sure the event is nothing short of sensational. Having been long-standing PreSonus users, we spoke to Dez Carpenter, Production Manager, about how PreSonus’ quality, price, and support ticks all the boxes for the Bentley Boys.

Dez is also a professional musician and has over 15 years experience playing professionally in Ireland. He came on board with Bentley Productions and Bentley Boys nearly ten years ago and has spent seven of these as their Production Manager. His roles within the company include event planning and execution, personnel management and training, and lead engineer. For Dez, having multiple systems out at any one time means he needs to have confidence in the product—which he’s found with PreSonus.

The Bentley Boys main digital mixer for stock is the StudioLive 16.0.2—and they have a lot of them! They have also now expanded to include the new StudioLive 24 (Series III) and StudioLive 24R rack mixer and are exploring the PA range to add to their inventory. In particular, the PreSonus AIR Series P.A. speakers have been selected to further enhance the quality of The Bentley Boys’ touring system. All of the PreSonus products are used for live FOH applications. High profile events, blue chip corporate clients, etc.

When asked what led the Bentley Boys to choose these particular PreSonus products, Dez Carpenter, Production Manager for the Bentley Boys states, “Our AV model is focused on small format, expandable, and minimal footprint equipment. The 16.0.2 was simply a no-brainer in terms of price, size, and functionality. It sounds better than anything else in its range, hands down. We’ve tried them all. The StudioLive 24 has transformed our larger events in terms of features and flexibility with the 24R.”

“PreSonus is a user-focused company,” he continues. “The community and support is so inclusive… you simply don’t get this from other companies. The equipment does exactly what it says on the tin, and it’s so intuitive. Training schedules are minimal, which is so important when taking on new personnel. The boards sound great, all our guys love using them and comment consistently how happy they are with their mixes.”

A big thing for the Bentley Boys that has proved to be particularly useful is that the presets work! “Before an event, I have total confidence to sit down in the lobby with the mixer and load my channels. I know that when the band is plugged in that my mix will be 95% of the way there. We get zero time on the majority of our events for soundcheck—the band is an afterthought most of the time, my mix position could be side stage, etc. To have total confidence in the product… I can’t put a value on that.”

When asked if there were any features on their wish list for PreSonus to add in future products, Dez explained that they are still working through the features on the StudioLive 24, and right now he can’t think of any. “I have been fortunate to A/B the StudioLive Series III alongside its competitors and without a doubt, it sounds better, is more flexible, and has a far better workflow. One of our events features two acts, split across two stages. The flexibility and layout of the DCAs are a big plus. The A/B option on each input is an awesome feature, along with the EQ variants. We are extremely happy to be working with the new additions to our PreSonus inventory and are greatly benefiting from even further flexibility the Series III mixers offer to our FOH requirements.”

Keep up with The Bentley Boys on Facebook!

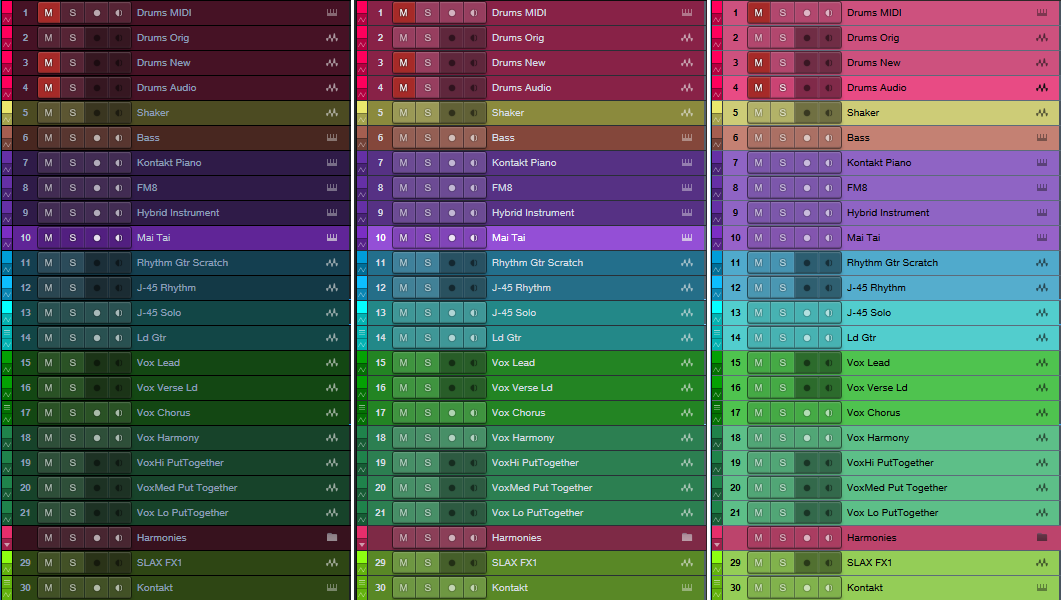

Friday Tip: Colorization: It’s Not Just About Eye Candy

Some people think colorization is frivolous—but I don’t. I started using colorization when writing articles, because it was easy to identify elements in the illustrations (e.g., “the white audio is the unprocessed sound, the blue audio is compressed”). But the more I used colorization, the more I realized how useful it could be.

Customizing the “Dark” and “Light” Looks

Although a program’s look is usually personal preference, sometimes it’s utilitarian. When working in a video suite, the ambient lighting is often low, so that the eye’s persistence of vision doesn’t influence how you perceive the video. For this situation, a dark view is preferable. Conversely, those with weak or failing vision need a bright look. If you’re new to Studio One, you might want the labels to really “pop” but later on, as you become more familiar with the program, darken them somewhat. You may want a brighter look when working during daytime, and a more muted look at night. Fortunately, you can save presets for various looks, and call up the right look for the right conditions (although note that there are no keyboard shortcuts for choosing color presets).

You’ll find these edits under Options > General > Appearance. For a dark look, move the Background Luminance slider to the left and for a light look, to the right (Fig. 1). I like -50% for dark, and +1 for light. For the dark look, setting the Background Contrast at -100% means that the lettering won’t jump out at you. For the brightest possible look, bump the Background Contrast to 100% so that the lettering is clearly visible against the other light colors, and set Saturation to 100% to brighten the colors. Conversely, to tone down the light look, set Background Contrast and Saturation to 0%.

Hue Shift customizes the background of menu bars, empty fields that are normally gray, and the like. The higher the Saturation slider, the more pronounced the colorization.

The Arrangement sliders control the Arrangement and Edit view backgrounds (i.e., what’s behind the Events). I like to see the vertical lines in the Arrangement view, but also keep the background dark. So Arrangement Contrast is at 100%, and Luminance is the darkest possible value (around 10%) that still makes it easy to see horizontal lines in the Edit view (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: The view on the left uses 13% luminance and 100% contrast to make the horizontal background lines more pronounced.

Streamlining Workflow with Color

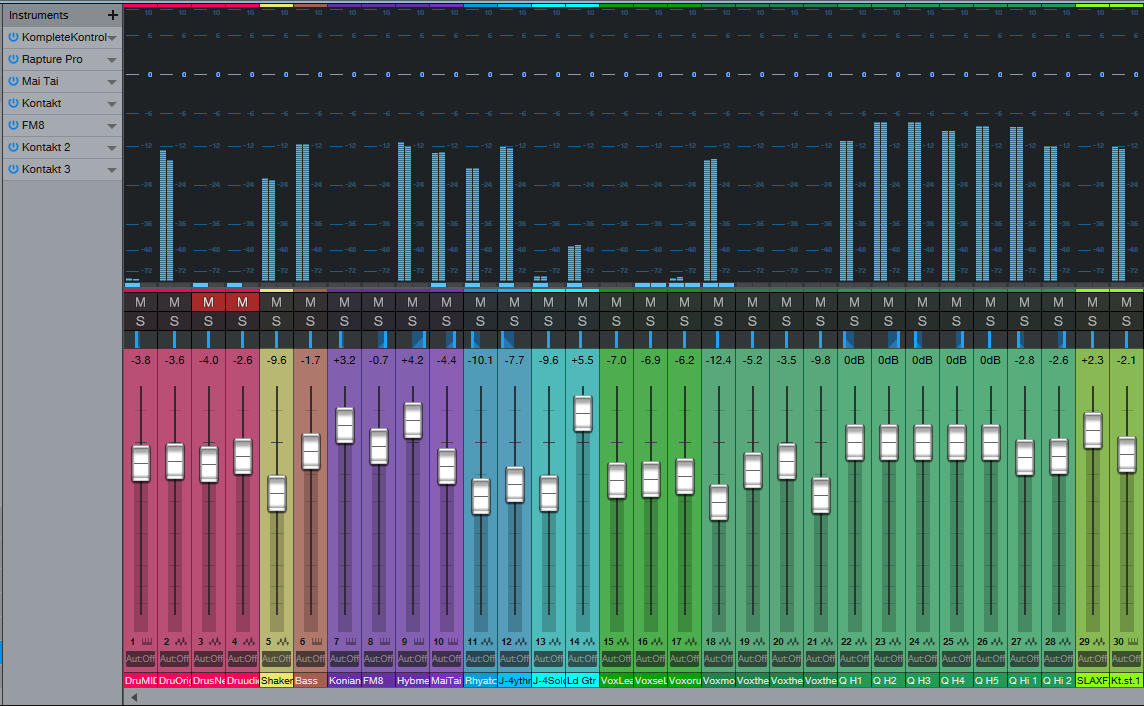

With a song containing dozens of tracks, it can be difficult to identify which Console channel strip controls which instrument, particularly with the Narrow console view. The text at the bottom of each channel strip helps, but you often need to rename tracks to fit in the allotted space. Even then, the way the brain works, it’s easier to identify based on color (as deciphered by your right brain) than text (as deciphered by your left brain). Without getting too much into how the brain’s hemispheres work, the right brain is associated more with creative tasks like making music, so you want to stay in that mode as much as possible; switching between the two hemispheres can interrupt the creative flow.

I’ve developed standard color schemes for various types of projects. Of course, choose whatever colors work for you; for example, if you’re doing orchestral work, you’d have a different roster of instruments and colors. With my scheme for rock/pop, lead instruments use a brighter version of a color (e.g., lead guitar bright blue, rhythm guitar dark blue).

- Main drums – red

- Percussion – yellow

- Bass – brown

- Guitar – blue

- Voice – green

- Keyboards and orchestral – purple

- FX – lime green

Furthermore, similar instruments are grouped together in the mixer. So for vocals, you’ll see a block of green strips, for guitar a block of blue strips, etc. (Fig. 3)

Figure 3: A colorized console, with a bright look. The colorization makes it easy to see which faders control which instruments.

To colorize channel strips, choose Options > Advanced tab > Console tab (or click the Console’s wrench icon) and check “Colorize Channel Strips.” This colorizes the entire strip. However, if you find colorized strips too distracting, the name labels at the bottom (and the waveforms in the arrange view) are always colored according to your choices. Still, when the Console faders are extended to a higher-than-usual height, I find it easier to grab the correct fader with colored console strips.

In the Arrange view, you can colorize the track controls as well—click on the wrench icon, and click on “Colorize Track Controls.” Although sometimes this feels like too much color, nonetheless, it makes identifying tracks easier (especially with the track height set to a narrow height, like Overview).

Color isn’t really a trivial subject, once you get into it. It has helped my workflow, so I hope these tips serve you as well.

Extra TIP: Buy Craig Anderton’s Studio One eBook here for only $10 USD!

Studio One 4.1.2 is available now!

Studio One 4.1.2 is a free maintenance update for all Studio One 4 users and includes a variety of improvements. Click “Check for Updates” in Studio One’s Start Page to get it!

- AAF Import/Export now supports volume automation

- AAF Export is now compatible with MOTU Digital Performer 9 (using legacy mode)

- A safety query has been added to the “Reset recent songs list” function

- Saving versions of a song is now more flexible with added control over how they affect the original song

- The song key signature is now included in the song meta data

- Quantize macros have been updated

- Multi-touch support now prevents “Mouse-as-Pointer” emulation for Plug-ins

- Time-stretching events in Arrangement is now reflected in the Audio Editor

Please click here to check out the latest release notes for a full list of fixes and improvements.

Friday Tips: The Virtual Pop Filter

Hate those p-pops and breath noises? So do I, especially when I’m being paid the big bucks for voiceovers and have to edit the pops out by hand. Granted, the Pauly pop filter is a fantastic solution—it’s the best pop filter I’ve ever tried—but its $300 price tag is pretty daunting. And no matter how hard you try to control pops at the source, sometimes those pesky, problematic pops work their way into a track anyway. So, it’s time for a do-it-yourself pop filter project. And because it’s virtual, this one doesn’t involve taking panty hose and stretching it over a hanger. Instead, we’ll stretch the Pro EQ into being a virtual pop filter.

The key is creating an ultra-steep cutoff frequency that kills the low frequencies, but lives below the range of the voice so it doesn’t thin out the vocal. The easiest way to create a steep cutoff is with multiple sharp notches (Fig. 1). There are four notches, all with a Q of 12 and a gain of -24 dB. Frequencies are 130, 140, 150, and 160 Hz.

Figure 1: Use notch filters to create a super-steep low frequency slope.

Now we need to get rid of the low frequencies. Enabling the Low Cut filter helps, but if we turn it up too far, it starts rounding off the slope, which makes it not as steep. A slope of 48 dB/octave, with a frequency around 90 Hz seems about right (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Adding a Low Cut filter starts carving away at the low frequencies.

That’s better, so it’s time for the coup de grâce—the Low Frequency Shelf stage. This gets rid of the remaining low frequencies, while still keeping the insanely steep slope (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: The Low Frequency Shelf completes the virtual pop filter.

However, note that the Low Frequency Shelf is also the key to versatility. By increasing the Q, you can add a low-frequency “bump” that’s just above the cutoff frequency. This adds extra depth, and a deep kind of vocal resonance that still keeps the p-pops under control.

Of course, every voice and mic is different, so you may want to edit the parameters somewhat. To preserve more bass, drop the frequency of all filter stages by 10 Hz and see if that helps. Conversely, if the p-pops are still too prominent, raise the frequency of all filter stages by 10 Hz until you hit the desired response…or if you’re impatient, use 20 to 30 Hz jumps.

In any event, you now have a super-steep low cut filter that can remove plosives, wind noises, most breath noises, earthquake sounds, and even the rumble from those pesky UFO flyovers—you might be surprised at just how effective this little project can be in banishing pops from your life.

Friday Tips: The Melodyne Envelope Flanger

This isn’t a joke—there really is an envelope-controlled flanger hidden inside Melodyne Essential that sounds particularly good with drums, but also works well with program material. The flanging is not your basic, boring “whoosh-whoosh-whoosh” LFO-driven flanging, but follows the amplitude envelope of the track being flanged. It’s all done with Melodyne Essential, although of course you can also do this with more advanced Melodyne versions. Here’s how simple it is to do envelope-followed flanging in Studio One.

- Duplicate the track or Event you want to flange.

- Select the copied Event, then type Ctrl+M (or right-click on the Event and choose Edit with Melodyne)

- In Melodyne, under Algorithm, choose Percussive and let Melodyne re-detect the pitches.

- “Select all” in Melodyne so that all the blobs are red, then start playback.

- Click in the “Pitch deviation (in cents) of selected note” field.

- Drag up or down a few cents to introduce flanging. I tend to like dragging down about -14 cents.

As with any flanging effect, you can regulate the mix of the flanged and dry sounds by altering the balance of the two tracks.

Note that altering the Pitch Deviation parameter indicates an offset from the current Pitch Deviation, not an absolute value. For example if you drag down to -10 cents, release the mouse button, and click on the parameter again, the display will show 0 instead of -10. So if you drag up by +4 cents, the pitch deviation will now be at -6 cents, not +4. If you get too lost, just select all the blobs, choose the Percussion algorithm again, and Melodyne will set everything back to 0 cents after re-detecting the blobs.

And of course, I don’t expect you to believe that something this seemingly odd actually works, so check out the audio example. The first part is envelope-flanged drums, and the second part applies envelope flanging to program material from my [shameless plug] Joie de Vivre album. So next time you need envelope-controlled flanging, don’t reach for a stompbox—edit with Melodyne.