Category Archives: Studio One

Four VCA Channel Applications

A VCA Channel has a fader, but it doesn’t pass audio. Instead, the fader acts like a gain control for other channels, or groups of channels. In some ways, you can think of a VCA Channel as “remote control” for other channels. If you assign a VCA to control a channel, you can adjust the channel gain, without having to move the associated channel’s fader. The VCA Channel fader does it for you.

Inserting a VCA channel works the same way as inserting any other kind of channel or bus. (However, there’s a convenient shortcut for grouping, as described later.) To place a channel’s gain under VCA control, choose the VCA Channel from the drop-down menu just below a channel’s fader…and let’s get started with the applications.

APPLICATION #1: EASY AUTOMATION TRIM

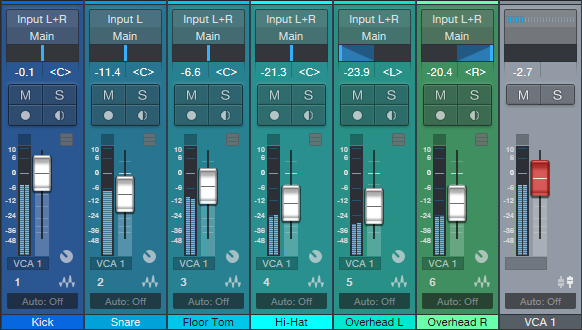

Sometimes when mixing, you’ll create detailed level automation where all the moves and changes are perfect. But as the mix develops, you may find you want to increase or decrease the overall level. There are several ways to do this, like inserting a Mixtool and adjusting the level independently of the automation, or using the automation’s Trim control. However, a VCA control is sometimes easier, and besides, it can control several channels at once if desired, without having to feed them to a bus. The VCA fader can even offset automation for multiple tracks that are located within a Folder Track (Fig. 1)

- Figure 1: Note how the label below each fader says VCA 1. This means each channel’s gain is being controlled by the VCA 1 fader on the right. If all these tracks have their own automation, VCA 1 can bring the overall level up or down, without altering the automation shape, and without needing to send all their outputs to the same bus.

If the automation changes are exactly as desired, but the overall level needs to increase or decrease, offset the gain by adjusting the VCA Channel’s fader. This can be simpler and faster than trying to raise or lower an entire automation curve using the automation Trim control. Furthermore, after making the appropriate adjustments, you can hide the VCA Channel to reduce mixer clutter, and show it only if future adjustments are necessary.

APPLICATION #2: NESTED GROUPING

One of the most common grouping applications involves drums—when you group a drum kit’s individual drums, once you get the right balance, you can bring their collective levels up or down without upsetting the balance. Studio One offers multiple ways to group channels. The traditional option is to feed all the outputs you want to group to a bus, and vary the level with the bus fader. For quick changes, a more modern option is to select the channels you want to group, so that moving one fader moves all the faders.

But VCAs take this further, because VCA groups can be nested. This means groups can be subsets of other groups.

A classic example of why this is useful involves orchestral scoring. The first violins could be assigned to VCA group 1st Violins, the second violins to VCA group 2nd Violins, violas to VCA group Violas, and cellos and double basses to VCA group Cellos+Basses.

You could assign the 1st Violins and 2nd Violins VCA groups to a Violins Group, and then assign the Violins group, Violas group, and Cellos+Basses group to a Strings group. Now you can vary the level of the first violins, the second violins, both violin sections (with the Violins Group), the violas, the cellos and double basses, and/or the entire string section (Fig. 2). This kind of nested grouping is also useful with choirs, percussion ensembles, drum machines with multiple outputs, background singers, multitracked drum libraries, and more.

Figure 2: The 1st Violins and 2nd Violins have their own group, which are in turn controlled by the Violins group. Furthermore, the Violins, Violas, and Cellos+Basses groups are all controlled by the Strings group.

Although it may seem traditional grouping with buses would offer the same functionality, note that all the channel outputs would need to go through the same audio bus. Because VCA faders don’t pass audio, any audio output assignments for the channels controlled by the VCA remain independent. You’re “busing” gain, not audio outputs—that’s significant.

If you create a group, then all the faders within that group remain independent. Although with Studio One you can temporarily exclude a fader from a group to adjust it, that’s not necessary with VCA grouping—you can move a fader independently that’s controlled by a VCA, and it will still be linked to the other members of a VCA group when you move the VCA fader.

Bottom line: The easiest way to work with large numbers of groups is with VCA faders.

APPLICATION #3: GROUPS AND SEND EFFECTS

A classic reason for using a VCA fader involves send effects. Suppose several channels (e.g., individual drums) go to a submix bus fader, and the channels also have post-fader Send controls going to an effect, such as reverb. With a conventional submix bus, as you pull down the bus fader, the faders for the individual tracks haven’t changed—so the post-fader send from those tracks is still sending a signal to the reverb bus. Even with the bus fader down all the way, you’ll still hear the reverb.

A VCA Channel solves this because it controls the gain of the individual channels. Less gain means less signal going into the channel’s Send control, regardless of the channel fader’s position. So with the VCA fader all the way down, there’s no signal going to the reverb (Fig. 3)

- Figure 3: The VCA Channel controls the amount of post-fader Send going to a reverb, because the VCA fader affects the gain regardless of fader position. If the drum channels went to a conventional bus, reducing the bus volume would have no effect on the post-fader Sends.

APPLICATION #4: BUS VS. VCA

There’s a fine point of using VCAs to control channel faders. Suppose individual drums feed a bus with a compressor or saturation effect. As you change the channel gain, the input to the compression or saturation changes, which alters the effect. If this is a problem, then you’re better off sending the channels to a standard bus. But this can also be an advantage, because pushing the levels could create a more intense sound by increasing the amount of compression or saturation. The VCA fader would determine the group’s “character,” while the bus control acts like a master volume control for the overall group level.

And because a VCA fader can control bus levels, some drums could go to an audio bus with a compressor, and some drums to a bus without compression. Then you could use the VCA fader to control the levels of both buses. This allows for tricks like raising the level of the drums and compressing the high-hats, cymbals, and toms more, while leaving the kick and snare uncompressed…or increasing saturation on the kick and snare, while leaving other drum sounds untouched.

Granted, VCA Channels may not be essential to all workflows. But if you know what they can do, a VCA Channel may be able to solve a problem that would otherwise require a complex workaround with any other option.

How to Use a Game Controller as a MIDI Device In Studio One!

Most of us who work here at PreSonus are musicians ???????or audio engineers ?.

And some of us are also gamers ?in addition to that.

For those of you who can relate, check out this interesting and fun video that PreSonus Artist/Endorser Nik Jeremić just created and shared with us recently. He’s using an Xbox One game controller to trigger samples in Studio One:

[Nik’s Official Website]

Tremolo: Why Be Normal?

Tremolo (not to be confused with vibrato, which is what Fender amps call tremolo), was big in the 50s and 60s, especially in surf music—so it has a pretty stereotyped sound. But why be normal? Studio One’s X-Trem goes beyond what antique tremolos did, so this week’s Friday Tip delves into the cool rhythmic effects that X-Trem can create.

TREMOLOS IN SERIES

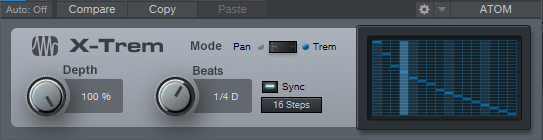

The biggest improvement in today’s tremolos is the sync-to-tempo function. One of my favorite techniques for EDM-type music is to insert two tremolos in series (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: These effects provide the sound in Audio Example 1. Note the automation track, which is varying the first X-Trem’s Depth parameter.

The first X-Trem runs at a fast rate, like 1/16th notes. Square wave modulation works well for this if you want a “chopped” sound, but I usually prefer sine waves, because they give a smoother, more pulsing effect. The second X-Trem runs at a slower rate. For example, if it syncs to half-notes, X-Trem lets through a string of pulses for a half-note, then attenuates the pulses for the next half-note. Using a sine wave for the second tremolo gives a rhythmic, pulsing sound that’s effective on big synth chords—check out the audio example.

BUILD YOUR OWN WAVEFORM

X-Trem’s waveforms are the usual suspects: Triangle, Sine, Upward Sawtooth, and Square. But what if you want a downward sawtooth, a more exponential wave (Fig. 2), or an entirely off-the-wall waveform?

Figure 2: Let’s have a big cheer for X-Trem’s 16 Steps option.

This is where the 16 Steps option becomes the star (Fig. 2) because you can draw pretty much any waveform you want. It’s a particularly effective technique with longer notes because you can hear the changes distinctly.

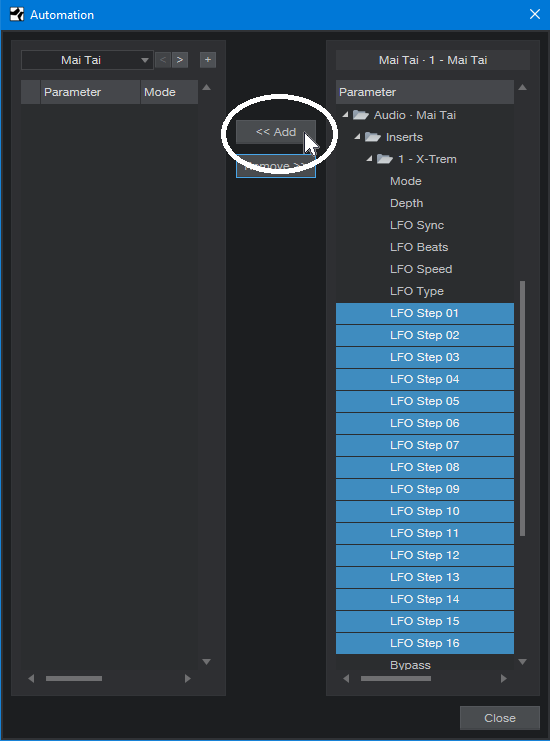

But for me, the coolest part is X-Trem’s “Etch-a-Sketch” mode, because you can automate each step individually, choose X-Trem’s Automation Write, and go crazy. Just unfold X-Trem’s automation options, choose all the steps, add them to the track’s automation, and draw away (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: Drawing automated step changes in real-time takes X-Trem beyond “why be normal” into something that may be illegal in some states.

Of course, if you just draw kind of randomly, then really, all you’re doing is level automation. Where this option really comes into its own is when you have a basic waveform for one section, change a few steps in a different section and let that repeat, draw a different waveform for another section and let that repeat, and so on. Another application is trying out different waveforms as a song plays, and capturing the results as automation. If you particularly like a pattern, cut and paste the automation to use it repetitively.

And just think, we haven’t even gotten into X-Trem’s panning mode—similarly to its overachieving tremolo functions, the panning can do a lot more than just audio ping-pong effects. Hmmm…seems like another Friday Tip might be in order.

The “Double-Decker” Pre-Main Bus

This Friday tip has multiple applications—consider the following scenarios.

You like to mix with mastering processors in the Main bus to approximate the eventual mastered sound, but ultimately, you want to add (or update) an unprocessed file for serious mastering in the Project page. However, reality checks are tough. When you disable the master bus processors so you can hear the unprocessed sound you’ll be exporting, the level will usually change. So then you have to re-balance the levels, but you might not get them quite to where they were. And unfortunately, one of the biggest enemies of consistent mixing and mastering is varying monitoring levels. (Shameless plug alert: my book How to Create Compelling Mixes in Studio One, which is also available in Spanish, tells how to obtain consistent levels when mixing.)

Or, suppose you want to use the Tricomp or a similar “maximizing” program in the master bus. Although these can make a mix “pop,” there may be an unfair advantage if they make the music louder—after all, our brains tend to think that “louder is better.” The only way to get a realistic idea of how much difference the processor really makes is if you balance the processed and unprocessed levels so they’re the same.

Or, maybe you use the cool Sonarworks program to flatten your headphone or speaker’s response, so you can do more translatable mixes. But Sonarworks should be enabled only when monitoring; you don’t want to export a file with a correction curve applied. Bypassing the Sonarworks plug-in when updating the Project page, or exporting a master file, is essential. But in the heat of the creative moment, you might forget to do that, and then need to re-export.

THE “DOUBLE-DECKER,” PRE-MAIN BUS SOLUTION

The Pre-Main bus essentially doubles up the Main bus, to create an alternate destination for all your channels. The Pre-Main bus, whose output feeds the Main bus, serves as a “sandbox” for the Main bus. You can insert whatever processors you want into the Pre-Main bus for monitoring, without affecting what’s ultimately exported from the Main bus.

Here’s how it works.

- Create a bus, and call it the Pre-Main bus.

- In the Pre-Main bus’s output field just above the pan slider, assign the bus output to the Main bus. If you don’t see the output field, raise the channel’s height until the output field appears.

- Insert the Level Meter plug-in in the Main bus. We’ll use this for LUFS level comparisons (check out the blog post Easy Level Matching, or the section on LUFS in my mixing book, as to why this matters).

Figure 1: The Pre-Main bus, outlined in white, has the Tricomp and Sonarworks plug-ins inserted. Note that all the channels have their outputs assigned to the Pre-Main bus.

- Insert the mastering processors in the Pre-Main bus that you want to use while monitoring. Fig. 1 shows the Pre-Main bus with the Tricomp and Sonarworks plug-ins inserted.

- Select all your channels. An easy way to do this is to click on the first channel in the Channel List, then shift+click on the last channel in the list. Or, click on the channel to the immediate left of the Main channel, and then shift+click on the first mixer channel.

With all channels selected, changing the output field for one channel changes the output field for all channels. Assign the outputs to the Main bus, play some music, and look at the Level Meter to check the LUFS reading.

Now assign the channel outputs to the Pre-Main bus. Again, observe the Level Meter in the Master bus. Adjust the Pre-Main bus’s level for the best level match when switching the output fields between the Main and Pre-Main bus. By matching the levels, you can be sure you’re listening to a fair comparison of the processed audio (the Pre-Main bus) and the unprocessed audio that will be exported from the Main bus.

The only caution is that when all your channels are selected, if you change a channel’s fader, the faders for all the channels will change. Sometimes, this is a good thing—if you experience “fader level creep” while mixing, instead of lowering the master fader, you can lower the channel levels. But you also need to be careful not to reflexively adjust a channel’s level, and end up adjusting all of them by mistake. Remember to click on the channel whose fader you want to adjust, before doing any editing.

Doubling up the Main bus can be really convenient when mixing—check it out when you want to audition processors in the master bus, but also, be able to do a quick reality check with the unprocessed sound to find out the difference any processors really make to the overall output.

Acknowledgement: Thanks to Steve Cook, who devised a similar technique to accommodate using Sonarworks in Cakewalk, for providing the inspiration for this post.

Starpoint Gemini 3 With Nikola Jeremić

For those of you who are not familiar with Nikola (Nik) Jeremić’s work on the previous iteration of the Starpoint Gemini videogame soundtrack, you can find out about that here.

This will be a “deep dive” into how Nik used Studio One Professional along with the ATOM and our Studio 1824c interface to route audio and MIDI data to and from external hardware synths… his own words!

ATOM Controller

The most important thing about ATOM in this production is that it is used both as a playable instrument, as well as editing and mixing controller.

The layout was very simple in terms that it already integrates itself perfectly with Studio One, and I didn’t have to do much with tweaking it.

So far it completely replaced my old Classic FaderPort (which I still own and use it from time to time) in regards to transport commands, writing automation for track levels, panning, and the amount of signal being sent to FX tracks. I will surely upgrade myself with the current FaderPort pretty soon because I have worn out the buttons on the old one from years of usage.

I used small sticky tags in order to label the four knobs, so I always know which knob controls which parameter.

After the transport tab buttons, the ones I used the most are Song Setup, Editor and instrument Show/Hide. It really speeds up my workflow, and it was especially helpful on this game. Since 80% of the game’s soundtrack was done in the box, browsing through instruments and editing their MIDI data was really easy and fast.

One of the things that really amazed me regarding ATOM was the fact that every pad is labeled with the corresponding default control in Studio One Editor. I rarely touched my computer keyboard for editing.

Whenever I wanted to make a quick edit of my parameters in Impact, or any other instrument that matter, I just hit that Show/Hide instrument button, and… voila! Everything is right there at my fingertips! I will talk more about ATOM and Impact XT later.

Studio 1824c Interface

I used FireStudio Project for over eight years, and it has been a solid workhorse of an interface for me throughout my career. It worked flawlessly until I had a power surge at my home, which fried some of my gear, including the interface, so THAT was the only reason I had to replace it.

It actually happened in the middle of my work on Starpoint Gemini 3, so I researched a little and decided to go with Studio 1824c as an upgrade. To be honest, it’s as if I never replaced my old interface, because PreSonus hardware is really great when it comes to communication with Studio One, so the only thing I had to do was to plug it in my PC and install the latest drivers, and that was it. My production of this soundtrack hasn’t stopped at all, because everything was so compatible, so I just had to re-connect a few audio cables. It took me only minutes and I was back on track.

Since 20% of the soundtrack to Starpoint Gemini 3 is done on hardware synths and instruments, Studio 1824C is a Godsend for connecting all four of my hardware synths:

My Yamaha DX7 was connected via splitter cable as a stereo unit to my inputs 5 and 6.

I also used my three analogue KORG synths: (Volca Bass, Volca Keys, Volca Kick) in stereo via another splitter cable which was connected to inputs 1 and 2, because these Volcas were used the most for this soundtrack.

All of the synths received their MIDI data via MIDI In/Out from Studio 1824c, and I am really happy I didn’t have to buy an external MIDI interface for this. The only thing I had to do was to plug and unplug the midi cables from one synth to another, depending which one I was using at that time, but it’s not a mood killer.

My inputs 3 and 4 were set up as mono. Input 3 has an external 1073 clone mic preamp attached to it, and Input 4 has an external DI for recording and re-amping guitars and bass.

Inputs 7&8 together with Outputs 7&8 were used as stereo FX loop send/return for my FX pedal chain with Pipeline Stereo plugin:

I also used sticky tags to label my front panel of Studio 1824C, and I mapped out my ins and outs inside song setup window, so I could save it as a default setting for all of my tracks for this game.

Regarding my FX chain loop, I used delay, chorus and shimmer reverb pedals in series, and I set them up to be used with Pipeline XT stereo plugin (which comes bundled with Studio One Pro) on an FX track. The reason I opted for this approach instead of connecting my synth output directly to pedals, is because I wanted to have an overall control of the amount of synth signal I am sending to any FX chain. Sometimes I wanted to automate the amount of signal being sent, and that is where those mapped knobs from ATOM came in handy.

I am pretty amazed by the build quality of Studio 1824c, having in mind the price of the unit. I absolutely love the front panel metering and big level knob for main out. Having two headphone outputs is really handy when I invite a session musician to record, because I don’t have a booth, then we both use headphones in the same room. Studio 1824c is a workhorse of an interface and it has improved my workflow ten times better than before.

I amhave yet to build my own Eurorack modular synth, so I can send CV signals via Studio 1824c outs to my synth. That is an AMAZING feature, and I am really looking forward to using it in the future.

Impact XT

Impact XT was an essential part of my beats and percussive materials for both action and exploration tracks, and the way ATOM integrates with Impact XT has been really helpful to my workflow throughout the course of this entire soundtrack.

I used two instances of Impact XT:

One was for triggering 80s synth drums and transition fills that you can hear in synthwave all the time. The first bank (BLUE) was for elements of the drum kit, and the second bank (GREEN) was for triggering drum fills for transitions between parts.

I love the fact I can trigger loops and audio clips inside Impact XT and sync them to the BPM of my track. All you have to do is to quantize each trigger pad to Follow Tempo and Beats, and no matter what tempo you’re in, it will work flawlessly.

One more thing I like about Impact XT and ATOM is that all the pads can be color-coded the way you like for each bank, because it really helps during the performance to know which pad corresponds to which sound or loop. The bank button on the ATOM itself responds to the bank color of Impact XT, which is really cool.

My second instance of Impact XT was for deep ambient hits and various atonal noises and synth FX for background. I mean, you can’t have a space exploration soundtrack without some weird alien sounds in the background, right??

I love the option of multiple stereo and mono outputs in Impact, so that was really helpful for me to have different FX chains for various drum sounds.

SampleOne XT

SampleOne XT is featuring my main piano sounds for the entire Starpoint Gemini 3 soundtrack. I haven’t recorded actual piano samples, instead I re-sampled a piano VST I am using most of the time for my work. The thing is that this sampled piano uses up a lot of RAM and CPU, so I couldn’t use it in real-time with my other instruments inside my template, because the piano was processed with a lot of plugins, and then it was introducing latency after I had to increase the buffer size.

In order to use the sounds that I wanted, I re-sampled this piano in two octaves note by note with the processing included. It was more convenient for me, and it saved me a lot of loading time of the template itself.

In order to use the sounds that I wanted, I re-sampled this piano in two octaves note by note with the processing included. It was more convenient for me, and it saved me a lot of loading time of the template itself.

SampleOne XT proved to be a great choice because it’s really user-friendly and convenient.

First, I had to edit and cut all of the individual notes and label them. That is the only tedious work I had to do here.

After that, all I had to do was to drag the sampled notes to their corresponding key inside Sample One XT. But… I opted for the faster and better solution of sample recording inside SampleOne XT.

Basically what I did was to place all of the samples on the grid, select the audio input inside Sample One XT, choose the starting note and Play, Stop, and Record buttons in order to tell the engine to separate notes. After that, I only renamed the files, and that was it.

After that was done, I was able to play my piano instantly. I saved the patch as a preset, so I could recall it any time.

It doesn’t get any simpler than that, and this is the reason I love Studio One.

Pattern Editor

As I said, ATOM and Impact XT are all over my percussive tracks and beats on this soundtrack, but I also used another drum VST plug-in here in order to make things sound a little bit organic, and I used my 80s synth drum kit as a layer on top of those organic drum parts. Call it some sort of a kick and snare drum sample trigger like you have in metal production.

The option that really inspired me and got my creative juices flowing is the pattern editor in Studio One 4.6.

The way I sequenced my drums and percussion was to play them in at first, and get the most humanization out of them based on velocity, sample offset etc… But then I took those performances and improved them inside Pattern Editor, changed a hit here and there, modify the rhythm, etc…

Basically, I had a drum performance on a midi piano roll with all the notes labeled properly, and then I right-clicked on the midi clip to select the option to convert it to drum pattern for editing.

Editing note data inside Pattern Editor is a breeze.

I could easily replace notes, create new performances, shift the beats and add some swing to them in order to make them sound more natural. The option for half-lane resolution is a really cool feature to add triplets and some odd hits, but it allows me to follow the pattern with precision. This is just one example of a pre-chorus pattern inside the action track, and you can clearly see the name of all the notes properly, and I love the way it integrates properly with third party drum VSTs.

It really is a beatmaking workhorse for electronic music. I have yet to test in on cinematic percussion with big drums and more elements.

MIDI FX

MIDI FX in Studio One (the arpeggiator especially) can come in handy if you don’t like the fuss of setting up some complex sequences.

I used arpeggiator mostly on action cues where I wanted to create running sequences in order to have that sense of tension going on during combat. It was mostly set up in 8th or 16th notes, and then I played wide chords on percussive synths in order to get them running and the results were stunning! The arpeggiator is really easy to use, and it was my go-to MIDI effect on this soundtrack.

I used arpeggiator mostly on action cues where I wanted to create running sequences in order to have that sense of tension going on during combat. It was mostly set up in 8th or 16th notes, and then I played wide chords on percussive synths in order to get them running and the results were stunning! The arpeggiator is really easy to use, and it was my go-to MIDI effect on this soundtrack.

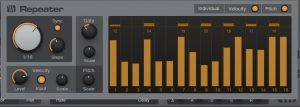

Repeater is a whole different beast, and this one is for people who  actually like working with complex sequences of scales and melodies. I used Repeater also mostly on action cues for the same reason as the Arpeggiator, but I programmed it to play some aggressive melodies that would counter the chords of the Arpeggiator. I actually have a hardware analogue sequencer, but this was easier and faster to use.

actually like working with complex sequences of scales and melodies. I used Repeater also mostly on action cues for the same reason as the Arpeggiator, but I programmed it to play some aggressive melodies that would counter the chords of the Arpeggiator. I actually have a hardware analogue sequencer, but this was easier and faster to use.

The real fun starts when you place a Chorder in front of Repeater!

What I did with Chorder was to make it play intervals like fifths or octaves, and then sequence those with either Repeater or Arpeggiator.

The results I got were some really complex action sequences which made the game developers smile from ear to ear! I highly recommend trying this approach.

Play Starpoint Gemini 3 here on Steam!

[ Nik’s Official Website | Starpoint Gemini 3 Soundtrack (Bandcamp) ]

Mixing the Killers in Studio One

There’s perhaps never been a better time to focus on your mixing craft—we’re all being encouraged to stay home, and Studio One is on sale. Why not try your hand at mixing an established hit?

Good ol’ Joe Gilder has just wrapped up his incredible three-episode series on Mixing The Killers in Studio One. Yeah, The Killers, as in “Mr. Brightside” and “Somebody Told Me.” In fact, “Somebody Told Me” is the song that Joe dissects and re-builds right before your eyes and ears.

Note that this is a deeeeeeep dive. You’re going to want to check your Instagram-influenced attention span at the door and spend some quality time with this; there’s three episodes here that range from a half-hour to an hour and a half long… but come on, it’s Joe Gilder. So you know it’s gonna be All The Killers and no The Fillers.

Ready? Let’s roll onto something new. Because Mixing The Killers is way more fun than killing the mixers.

Also, didja know how Joe got the multi-tracks for this song? From none other than Mix The Music. Mix The Music offers a unique .multitrack audio project format that can only be opened in Studio One. You can purchase the stems to your favorite hit songs, re-mix, and play along! And right now, PreSonus fans can get 20% off any purchase at Mix The Music using promo code: KillerDeal.

Furthermore, don’t forget that Studio One and Notion are both 30% off in April, including upgrades!

Melodic Percussion

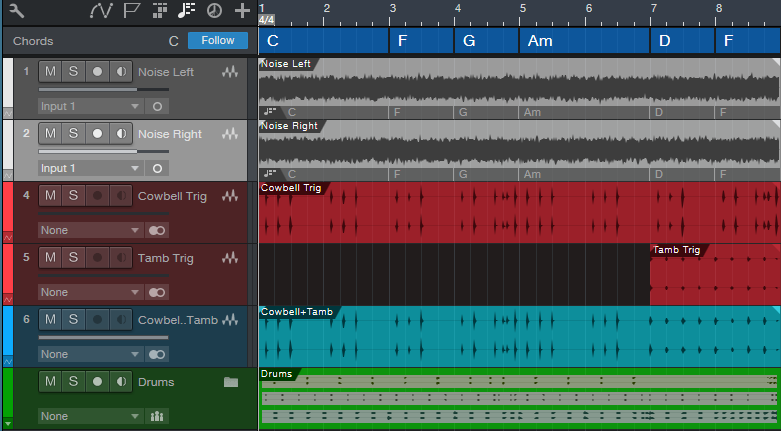

This week’s tip shows how to augment percussion parts by making them melodic—courtesy of Harmonic Editing.

The basic idea is that setting a white or pink noise track to follow the chord track gives the noise a sense of pitch. Although having a long track of noise isn’t very interesting, if we gate it with a percussion part, then now we’ve layered the percussion part’s rhythm with the tonality of the noise. Add a little dotted 8th note echo, and it can sound pretty cool.

Step 1: Bring on the Noise

Noise needs to be recorded in a track to be affected by harmonic editing, so open up the mixer’s Input section, and insert a Tone Generator effect in tracks 1 and 2. Set the Tone Generator to Pink Noise, and trim the level so it’s not slamming up against 0 (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: We need noise in each channel to implement this technique.

Record-enable both tracks (set them to Mono channel mode), enable Input Monitor, and start recording noise into the tracks. The reason for recording into two tracks is we want to end up with stereo noise, so the tracks can’t be identical.

Step 2: Make the Noise Stereo

Now that the noise is recorded, you can remove the Tone Generator effects from the track inputs. At the mixer, pan one channel of noise left, and one right. In each track’s Inspector, choose Universal Mode for Follow Chords, and Strings for Tune mode (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: How to set up the tracks for stereo noise. The crucial Inspector settings are outlined in yellow.

Set each track’s output to a Bus, and now we have stereo noise at the Bus output. Insert a Gate in the Bus, and any other effects you want to use (I insert a Pro EQ to trim the highs and lows somewhat, and a Beat Delay for a more EDM-like vibe—but use your imagination).

Step 3: Control the Gate’s Sidechain

Choose the percussion sound with which you want to control the Gate sidechain, insert a pre-fader send in the percussion track, assign the send to the Gate, and then adjust the Gate parameters so that the percussion track modulates the noise percussively. Fig. 3 shows the track setup.

Figure 3: Track layout used in the audio example.

Tracks 1 and 2 are the mono noise tracks that follow the Chord Track, and feed the Bus. Tracks 4 and 5 both have pre-fader sends to control the Gate, so that for the first 7 measures only the cowbell controls the gate, but at measure 8, a tambourine part also modulates the Gate.

Track 6 has the cowbell and tambourine audio, which is mixed in with the pitched noise, while the folder track has the kick, snare, and hi-hat loops. (The reason for not using post-fader sends on the percussion tracks is so that the tracks controlling the Gate are independent of the audio, which you might want to process differently.)

But Wait…There’s More!

With a longer gate, the sound is almost like the rave organ sound that was so big at the turn of the century. And there are options other than gating, like using X-Trem…or following the Gate with X-Trem. Or draw a periodic automation level waveform for the bus, and use the Transform function to make everything even weirder. In any case, now you have a new, and unusual tool, for percussive accents.

Keyboard Meets Power Chords

Hey keyboard players!

Do you feel kind of left out because of the cool guitar amps that Studio One added in version 4.6? Well, this week’s tip is all about having fun, and bringing power chord mentality to keyboard, courtesy of those State Space amps. Listen to the audio example, and you’ll hear what I’m talking about.

And so you can get started having fun, you don’t even have to learn what’s going on to get that sound you just heard. Download Power Chordz.instrument, drag it into the track column, feed it from your favorite MIDI keyboard, and start playing.

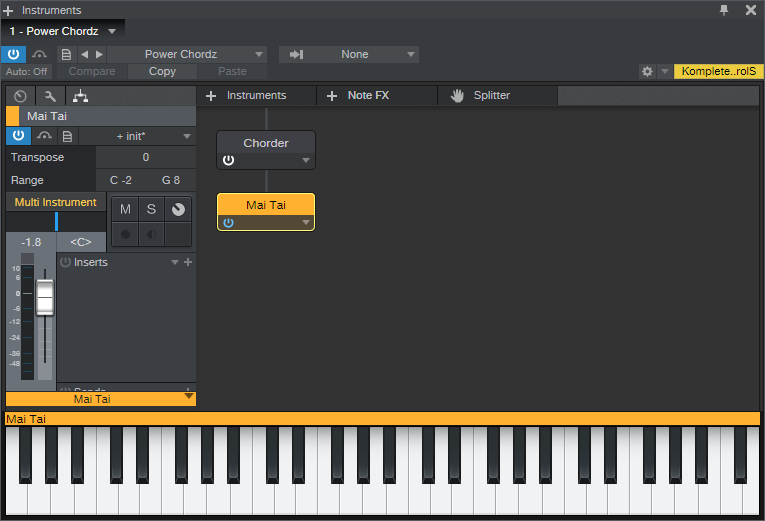

Now, I know some of you prefer just to download a preset and get on with your life, and that’s fine—but for those who want some reverse engineering, here’s what’s under the hood.

Figure 1: The Multi-Instrument is pretty basic—it just bundles a Chorder Note FX and Mai Tai together.

The preset starts with a Multi-Instrument (Fig. 1) that consists of the Chorder Note FX, and Mai Tai synthesizer. The Chorder plays tonic, fifth above, an octave above, octave+fifth above, and two octaves above when you hit a keyboard key—your basic “it’s not major, and it’s not minor” type of power chord.

The Mai Tai uses a super-simple variation on the Init preset. In Fig. 2, anything that’s not relevant is grayed out. Turn off Osc 2, Noise, LFO 1, and LFO 2. There’s no modulation other than pitch bend, and no FX. Envelope 2 and Envelope 3 aren’t used. I set Pitch Bend to 7 semitones to do whammy bar effects, but adjust to taste. Also, you might want to play around with the Quality parameter. I’m allergic to anything called “normal,” so if you are as well, try the 80s, High, and Supreme settings to see if you like one of those better.

Figure 2: The Mai Tai preset uses simple waveforms, which is what you want when feeding amp sims and other distortion-oriented plug-ins.

Look in the instrument’s mixer channel, and you’ll see four Insert effects: Pro EQ, Ampire, Open Air, and Binaural Pan. You can check out their settings by opening them up, but the Ampire settings (Fig. 3) deserve a bit of explanation.

Figure 3: Ampire is using the Dual Amplifier and 4×12 MFB speaker cabinet, but just about any amp and cab has their merits.

The reason for choosing the Dual Amplifier is because it’s really three amps in one, as selected by the Channel knob on the right—I figured you’d appreciate having three separate sounds without having to do anything other than adjust one knob. Try different cabs and amps, but be forewarned—you can really go down an Endless Rabbit Hole of Tone, because there are a lot of great amp and cab sounds in there. I’ll admit that I ended up playing with various permutations and combinations of amps, effects, and cabs for hours.

You can also get creative with the Mai Tai, specifically, the Character controls. I didn’t assign any controls to a Control Panel, or set up modulation because having a pseudo-”whammy” bar pitch wheel was enough to keep me occupied. But, please feel free to come up with your own variations. And of course…post your best stuff on the PreSonus Exchange!

Up Your Expressiveness with Upward Expansion

Many people don’t realize there are two types of expansion. Downward expansion is a popular choice for minimizing low-level noise like hiss and hum. It’s the opposite of a compressor: compression progressively reduces the output level above a certain threshold, while a downward expander progressively reduces the output level below a certain threshold. For example, with 2:1 compression, a 2 dB input level increase above the threshold yields a 1 dB increase at the output. With 1:2 expansion, a 1 dB input level decrease below the threshold yields 2 dB of attenuation at the output.

Upward expansion doesn’t alter the signal’s linearity below the threshold—if the input changes by 2 dB, the output changes by 2 dB. But above the threshold, levels increase. For example, with 1:2 expansion, a 1 dB increase above the threshold becomes 2 dB of increase at the output. Fig. 1 shows the difference between downward and upward expansion.

Figure 1: The top screen shot shows how downward expansion attenuates levels below a threshold, while the lower one shows how upward expansion increases levels above a threshold.

That’s Nice…So What?

Upward expansion is a useful tool for drums, hand percussion, and other percussive instruments. One function is transient shaping, to emphasize attacks. Suppose you have a drum loop with too much room sound. Traditional expansion can make the room sound decay faster, but using upward expansion brings the peaks above the room sound, while leaving the characteristic room sound alone.

Another use is with percussion parts, like hand percussion, that are playing along with drums. A lot of times you don’t want the percussion hits to be too uniform in level, but instead, the most important hits should be a little louder compared to the rest of the part. Again, that’s where upward expansion shines. Dip the threshold just a tiny bit below the peaks—the peaks will stand out, and sound more dynamic.

Let’s listen to an audio example. The first two measures use no upward expansion with a drum track. The next two measures add a subtle amount of upward expansion. You’ll hear that the peaks from the kick and snare are still prominent, but the room sound and cymbals are a bit lower by comparison. The final two measures use the settings shown in Fig. 2. The kick and snare peaks are still there, but the rest of the part is more subdued, and the overall sound is “tighter,” with more dynamics.

Figure 2: Expander settings for the Upward Expansion Demo.

The only difference among the two-measure sections is the Range control setting. For the first two measures, it’s 0.00 dB; nothing can be above the threshold, because there is no threshold. In the second two measures, the Range is -2.00, so anything above that threshold goes through 1:4 expansion. In the final two measures, the range is -4.00 (I rarely take it lower, as long as the Event hits close to 0 on peaks).

Here’s the coolest part: Automating the Range parameter lets you alter a drum part’s dynamics and feel, without having to change the part itself. This is particular wonderful for compressed drum loops, because you can lower the range to keep the peaks, while making the rest of the loop less prominent. When you want a big sound, slam the Range back up to 0.00.

But Wait! There’s More!

The Multiband Dynamics processor can do frequency-selective upward expansion. You can isolate just the high frequencies where a drum stick hits, and emphasize only that frequency. Another use is making acoustic guitars sound more percussive, as in this audio example.

The first two measures are the original acoustic guitar track, and the next two use Multiband Dynamics to accent the strums (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: This setup takes advantage of the Multiband Dynamics’ ability to add upward expansion to a specific frequency range. Note the Input level control adding gain (outlined in white).

The Multiband Dynamics are in a separate, parallel track (you could build this into an FX Chain, but I think showing this in two channels illustrates the process better). Because the Multiband Dynamics is listening to only the high frequencies, which are quite weak and not sufficient to go over the expander threshold, the Input control is adding +10 dB of gain. Alternately, you could insert a Mixtool before the Multiband Dynamics.

This effect is best when used subtly, but next time you want to reach for a transient shaper, try this instead. It’s a flexible way to emphasize percussive hits and strums.

Sascha Konietzko (KMFDM) Talks Studio One

Hello… this is Sascha Konietzko a.k.a Käpt’n K, a native of Germany, founder of KMFDM in 1984 (when I was living in Paris, France), a producer and remixer for the past 35+ years.

Besides KMFDM, I’ve done work to more or lesser degrees of involvement with a number of projects on the side: MDFMK, EXCESSIVE FORCE, KGC, SCHWEIN, PIG, and SKOLD, to name a few. As a remixer, I was fortunate enough to contribute to bands such as Metallica, Rob Zombie, Megadeth, The Young Gods, Front 242, Die Krupps and many more.

Under the moniker KMFDM, I have released 21 studio albums, as well as dozens of singles, EPs and live albums.

I’ve been using the PreSonus StudioLive 24.4.2 digital console mixer for live shows (monitor setup) for a number of years now, as well as Studio One Professional and the trusty ol’ Studio Channel. Studio One Professional has been used in my personal studio, mainly to record vocals.

So here’s the story: I’ve been using Pro Tools since 1991; previously I’ve worked with the earlier version of it, which was Sound Designer II. Over the years Pro Tools evolved into a platform with many great features, but also many (not to be underestimated) negative aspects—such as severe latency, under some circumstances.

When I discovered Studio One, which was actually highly recommended to me by KMFDM’s drummer Andy Selway, I found out that I could easily use the workflow I’ve come to develop over the years with the click of a button, PLUS… and this is the absolutely greatest feature of Studio One Professional in my mind: without any latency AT ALL. It allows me to interchange seamlessly between my recording and my mixing environments!

Seriously, it’s been a lifesaver after so many situations where a recording session just went downhill really quick due to latency issues in Pro Tools, with frustrated performers and a super-frustrated Yours Truly!

Website | Spotify | YouTube | Instagram | Facebook | Twitter