Monthly Archives: July 2024

Creative FX Sound Design

By Craig Anderton

It’s been a while since we’ve had a post for sound design fans. So, let’s create some crazy FX for sci-fi/suspense/horror movies, DJ breaks, or even background sounds for weird social media videos. We’re going to convince Studio One that feedback is good, and in the process, nail some of the early electronic music sounds from the 50s—before synthesizers walked the face of the earth. Check out the audio examples at the end.

It’s All About the Feedback

Inserting processors in a feedback loop allows altering the feedback effects. Note that I didn’t say “controlling” the feedback effects, because feedback is a highly unpredictable process. So, part of this tip involves real-time recording of the effects you create. Then, you can cut the best parts, process them further, do transposition, crossfade different sections to cut out the unusable parts, and so on.

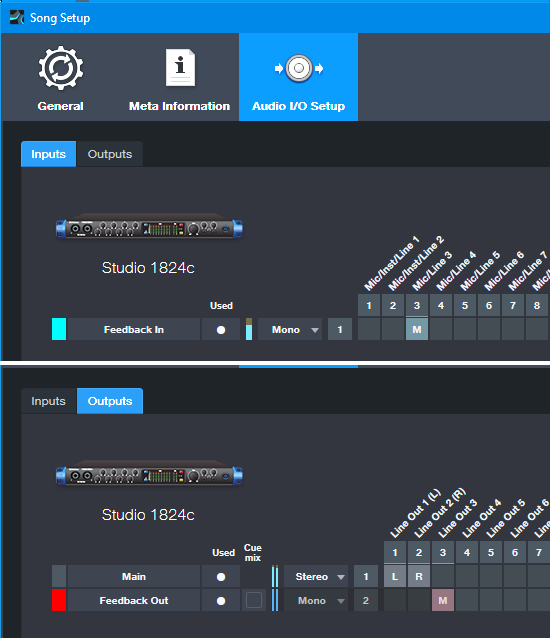

It’s helpful to create a dedicated sound design Song Setup (fig. 1). This setup requires a patch cord to connect an audio interface output to the same-numbered audio interface input. In this case, the output is mono but it could also be stereo. That would require two patch cords connecting like-numbered audio interface inputs and outputs.

Figure 1: Song Setup for creating a feedback loop inside Studio One. This uses the Studio 1824c’s Mic/Line 3 for the Input and Line Out 3 for the output.

The Channel Layout

Fig. 2 shows the channel layout. Here’s how it works.

Figure 2: Channel layout to create feedback-based sound effects.

The sound creation occurs in the FX track’s channel. Set the channel input to the Sound Setup’s Feedback In, and the output to Feedback Out. So, the output feeds back to the input through the physical patch cord. Note that the Input Monitor must be on.

Insert effects to process the feedback. Some effects are more useful than others. The Pro EQ3 is one of my favorites, but Rotor, Reverb, using the Tone Generator to initiate feedback, and several others are also fun. Also try using the Vocoder, with a separate track of white noise feeding its sidechain.

Feedback effects generate a lot of signal level. Normally we’d just set up a track to record the FX Track’s channel, but the FX channel fader also affects the feedback. It’s best to keep it at a fixed level. So, a Send from the FX channel goes to the FX Out bus. The FX Out bus’s output goes to the FX Record channel’s input. This gives two ways to vary the recording level: The Send from the FX Channel, and the FX Out bus fader.

Recording Time

Now it’s time to get crazy. It takes a while to get the feel of how to control this, so keep the monitor levels way down. Seriously. You don’t want to damage your ears.

Start off with just the Pro EQ3. At first, you probably won’t hear anything because the feedback hasn’t started up yet. Increase the gain of various EQ stages, and the feedback will kick in. Change gain, frequency, and other parameters of various EQ stages to change the feedback’s character.

Once you get a sense of how the process works, start recording. One cool trick is to do multiple automation passes. Record one pass varying one stage’s parameters, then in Touch mode, do a second pass varying a different stage’s parameters.

The Final Process

After recording your sound sources, process them further. Time- and pitch-stretching is helpful, but so is flanging, various impulses for the Open Air, Ampire’s amps and effects, and so on. You’ll get sounds you can’t obtain any other way…like the following 1-minute audio example, which plays five short snippets of different sound effects.

Brandon Ellis | Take the Leap | Quantum Audio Interfaces

The Black Dahlia Murder guitarist and New Jersey native talks about taking his leap.

A life in music requires passion, creativity, dedication – and for many creators, their trajectory can be traced back to a defining moment that changed everything: the moment they took the leap.

New Jersey native Brandon Ellis is the lead guitarist for the legendary American melodic death metal band, The Black Dahlia Murder. Renowned for his technical prowess and blisteringly fast solos, Brandon’s virtuosic style is a rich sonic tapestry of classical influences, archetypal 80s shred, and mind-bendingly modern techniques that continue to push the boundaries of extreme metal into uncharted territory.

Watch as Brandon records and re-amps a scorching new riff through the all-new PreSonus Quantum HD 2 Audio Interface, and talks about his early experiences with music, the necessity of discipline, and paying tribute to the greats that came before him.

“Since before I can even remember, I’ve been doing whatever I could to experience rhythm and music.” These words from Brandon Ellis encapsulate the essence of his musical journey: an innate and indomitable passion for expression. As a child, he drummed beats around the house, even using his teeth as makeshift percussion instruments, all while immersing himself in classic rock that sparked his desire to pick up the guitar.

“I was using music to escape. To experience new emotions. I wanted to know why a certain chord or scale could make me feel the way it did.” Ellis’s curiosity and thirst for understanding ultimately led him to seek out the secrets of guitar virtuosos like Eddie Van Halen, Yngwie Malmsteen, Mattias Eklundh, and Blues Saraceno. He pursued music theory rigorously, jammed with fellow musicians who shared his passion, and sought mentorship from some of the greatest guitarists in the world.

In spite of his passion, Ellis wasn’t planning on pursuing it as a career. So he enrolled in college, initially studying business. But as time went on, Ellis couldn’t ignore his calling. “All I wanted to do was play music, so when I was a freshman in business school and got the call to go on tour, the decision was obvious. I took the leap.” The opportunity to tour catapulted him from academia to the stage, and he never looked back.

From his humble beginnings drumming beats on his teeth to commanding stages worldwide, Ellis’ journey is a testament to perseverance and passion. His path, paved with music theory and hard won wisdom from guitar legends, embodies the spirit of relentless pursuit. Whether shredding with The Black Dahlia Murder or creating exclusive guitar lessons via his Shred Light District Patreon, Ellis continues to mesmerize with his technical prowess and deeply emotive solos.

Brandon’s story reminds us that pursuing our passions often requires courage and determination. It’s a journey where each chord strummed and every note played becomes a part of a larger narrative—a narrative of rhythm, melody, and the unwavering pursuit of musical mastery.

PreSonus products used: PreSonus Quantum HD 2 USB-C Audio Interface.

Meet the all-new family of Quantum USB-C Recording Audio Interfaces, and get in-depth information about the entire product line here.

A Dive Into Inside-Out Mixing

By Craig Anderton

There’s no “right” or “wrong” way to mix. For example, many successful engineers adjust individual tracks, and then mix groups of tracks. That’s fine, but as much as possible, I prefer to mix with sounds in context. I also no longer mix linearly, from start to finish, as was done with tape.

There’s a mixing technique that works well for me with typical songs that don’t have huge amounts of tracks. “Inside-out” mixing starts more in the middle of a song, and works its way out toward the beginning and end. This maintains a consistent sound quality through a song, and speeds up the mixing process. Maybe this method will work for you, too.

Part 1: Mix the “Big Chorus”

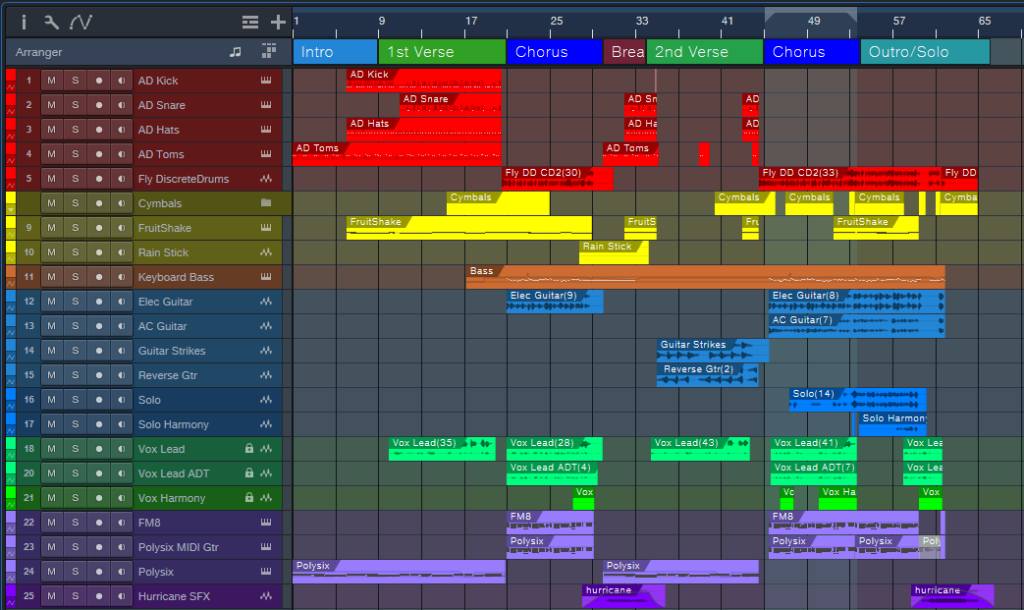

Start by placing a loop around the busiest, densest part of the song where the greatest number of tracks are playing at once (fig. 1). With a traditional mix, this will often be “the big chorus.” This is the “inside” part of inside-out mixing. In fig. 1, note that this loop (outlined in white) captures the drums, percussion, cymbals, bass, dual guitars, doubled lead vocals, harmony vocal, the first part of a solo that goes to the end, and dual keyboards.

Balancing all these crucial elements at once guarantees mixing in context. Also, if they work well together, they’ll almost certainly work well together with parts of the mix that are less dense. The objective is to tame the most difficult part of the mix early in the mixing process, which makes the rest of the mix flow more easily.

Figure 1: Tracks for my latest YouTube release, Inside the Eye of the Hurricane. The looped section that starts the mixing process is outlined in white.

Furthermore, I begin with minimal effects except for EQ. There are no sends or automation. The goal is to have a reference mix of as many tracks as possible that play simultaneously, yet be able to hear them all distinctly. (As usual, I start with everything panned to center. The reason why was described in a blog post from 2019, but the PreSonus archives no longer go back that far. You can find a revised version of the post on page 18 in The Huge Book of Studio One Tips & Tricks, 2nd Edition.)

After setting the reference levels, I add EQ and then re-adjust the levels. The looped section should now sound closer to what you want.

Part 2: Mix the Other Chorus(es)

Now loop an earlier chorus. It’s likely this will have a sparser arrangement, so that the later chorus can have more impact. The odds are excellent that the reference mix will still work for this chorus. If not, I usually use an Event envelope if any levels need to go up or down a bit. Automation doesn’t get added until the very end.

Part 3: Mix the Verse Between the Choruses

Next, loop the last measure or two of the previous chorus, the first two measures of the big chorus, and the verse between the choruses. Now you can mix the verse in context with coming out of the first chorus and going into the second one. This makes it easier to have a good flow from section to section.

Part 4: Loop Other Sections

Maybe there’s a bridge, a solo, another verse, whatever. By now, you get the idea: Loop sections of the song for mixing, and incorporate a little bit of what leads into the loop, as well as what follows it. I mix the beginning and end last, because with the rest of the song in place, it’s easy to figure out how to have them introduce and exit the song.

Part 5: Decorate the Mix with Ear Candy

At this point, you should have a solid, if not necessarily spectacular, mix. Insert some buses for reverb, delay, and various other effects, then route sends to them. Insert other processors, like dynamics, chorusing, more radical types of EQ, etc. Add the elements that make a mix interesting, and introduce elements of surprise.

Part 6: Automation

You’re in the home stretch. Now it’s time to think of the entire mix, not just the individual sections. For now, avoid the temptation to use master bus processing. Make the entire mix as wonderful as possible, and use master bus processing only for occasional reality checks.

Part 7: Finalize Your Mix

Finalize the mix with master bus processors if that’s your workflow, or transfer over to the Project Page to do your mastering.

About Some of the Ear Candy

The song “Inside the Eye of the Hurricane” also uses many of the techniques covered in previous blog posts. I thought you might enjoy hearing them in context.

Authentic ADT (Automatic Double-Tracking) is the only technique I use for double-tracking vocals because it sounds more like physical double-tracking than anything else I’ve found. It’s used on the choruses, but not the verses, so it’s easy to hear the difference.

Authentic 60s Flanger for Artist processes the crazy drum break, which also uses reversed audio. This happens just before the song’s second chorus.

A Guitar Solo Trick You’ve Never Heard Before was about solos, but this part of the song uses the reversed technique with chords to create pseudo-feedback effects.

Why I Don’t Use Compressors Anymore is certainly true here. The only compressor provides a special effect on the reversed guitar chords. There’s about 4 dB of limiting on vocals and 3 dB of drums. The vocal dynamics processing relies almost exclusively on phrase-by-phrase normalization and gain envelope dynamics. These techniques were also covered in blog posts that are no longer available. However, they’re described starting on page 484 in the eBook referenced above.

The techniques described in Fix Boring Acoustic Drum Loops is one reason why the acoustic drum loops in the choruses sound played instead of programmed. (The electronic drums in the verses are played in real time.)

Finally, there are two versions of the song posted online. One is conventional stereo. The other is binaural stereo that gives a more immersive sound when heard over headphones. Many people still don’t realize that you don’t need a surround system to take advantage of Atmos. As described in the blog post Easy Atmos: Grab Headphones, Mix, Have Fun, you can use Atmos to render your music in a binaural two-channel format designed for headphones. The sound is fuller and more satisfying than conventional stereo.

As just one example of what Atmos can do, there are synth filter sweeps in both versions of the song. However, the binaural version allows processing the filter spatially by making the sound more distant, and wider, as the filter cutoff increases. It’s a subtle effect, but far more expressive than simply turning up the filter’s cutoff frequency. For me, inside-out mixing also works well with Atmos. Because you’re mixing the densest part of the song first, you’re also creating a space that translates to the rest of the mix.

5 Session-Saving Tips for Studio One

By Craig Anderton

I admit it: the following tips are based on personally embarrassing experiences. I like to work fast to keep the creative juices flowing, but that can lead to occasional mistakes. Fortunately, these tips can help prevent a session from accidentally going south.

Track Lock

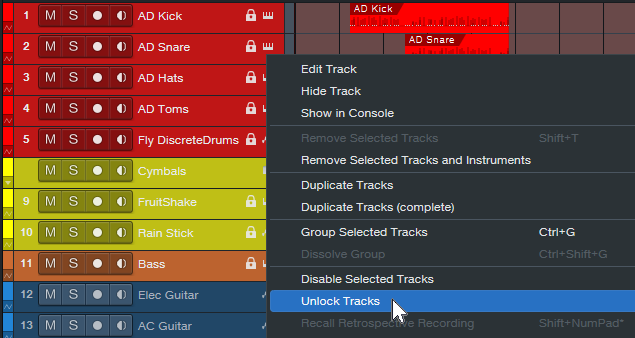

To lock track Events to their timeline positions, right-click on the track’s header and choose Time Lock (fig. 1). One application is locking tracks before mixing. Although the mixing console has full functionality, if you switch over to the Arrange window to set up loop points, confirm which tracks are in folders, and the like, a slip of the mouse won’t cause accidental edits.

I also use this with my “authentic ADT” technique, which requires placing two tracks at precise timeline positions. Locking both tracks maintains those positions. (Note: Even when locked, some non-critical editing functionality, like renaming, remains available.)

Figure 1: Right-click on a track and then choose to lock or unlock it. When locked, a lock symbol appears in the track header’s upper right.

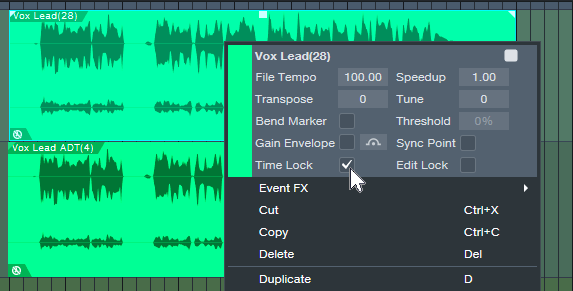

Time Lock and Edit Lock

These are more granular locking options (fig. 2). Right-click on an Event or Events, and choose one or both:

- Time Lock prevents the Event from moving on the timeline. You can still do edits like alter fades.

- Edit Lock prevents making accidental edits.

Figure 2: Protect an individual Event or Events from being edited, having timeline positions changed, or both.

Pseudo-Retrospective Recording for Audio

Although not as sophisticated as Retrospective Recording for MIDI Events, Studio One 3 introduced a similar function for audio. When enabled, Studio One is always listening to your audio inputs, and capturing the audio in buffers. When you start recording, the file includes audio that occurred before you clicked on record. After recording, you don’t see the captured audio. However, slip-editing the beginning of the audio to the left reveals the “pre-record” audio.

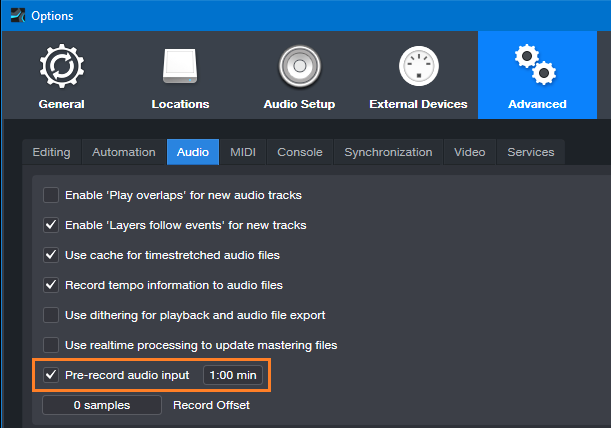

To set up Pre-Record audio, choose the Advanced Options, and select the Audio tab. Check Pre-Record Audio Input, and specify the number of seconds you want to capture (fig. 3). The maximum is one minute, but with lots of inputs this uses quite a bit of buffer memory. 10 or 15 seconds usually suffices.

Figure 3: Missed the first few seconds of a take? Relax—you had Pre-Record Audio Input checked.

Two other cool features include:

- Pre-Record saves the audio for any track that’s record-enabled. So, suppose a drum set has five miked tracks, and the drummer plays some amazing intro but you were late clicking on record. You can slip-edit all five recorded tracks to recover the audio.

- Pre-Record can handle interruptions. Let’s assume a guitarist plays some great riff and then stops, but you missed it. So, you click on record, and pre-record captures the sound you missed. But then the guitarist says “hey, don’t record me yet, I’m not ready.” So, you click out of record, with the transport still going while you wait. Unexpectedly, the guitarist plays an even better version of the riff. So, you hit record again. Now the guitarist is settled in and plays for real. When you stop recording, the file will include both of the pre-record riffs, as long as the combined length didn’t exceed the buffer time.

Prevent Ripple Edit Mishaps

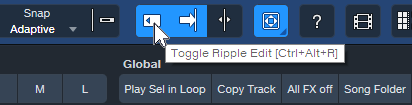

Ripple Editing allows edits like removing a section of a track, and having the track close up to fill the hole created by deletion. Or, insert an Event, and have it push the track later to make space for the addition. That’s cool, but if you leave Ripple Edit on accidentally, doing any subsequent cuts or pastes could mess up multiple Event positions in a song. Always disable Ripple Edit immediately after making your edit (fig. 4). Some people delete the keyboard shortcut, so that fat fingers can’t enable ripple editing accidentally.

Figure 4: Be sure to toggle Ripple Editing off after you’ve made a ripple edit.

Lock Events to Video “Hit Points”

Time Lock locks Events to bars and beats. However, when working with video, you often want to lock a sound effect to an absolute time in hours and seconds. That way, even if the background music’s tempo needs to change, the intergalactic cosmic explosion will still happen at the exact frame in the video where the planet blows up.

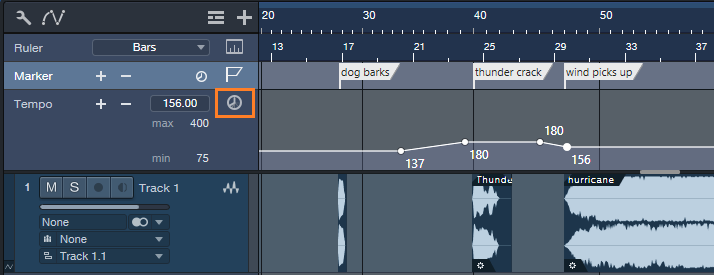

Studio One can ‘t lock Events to the Seconds Timebase, but there’s a workaround. You can lock Markers to specific times by toggling from bars/beats to seconds in the Marker track (fig. 5), and then relate Events to Markers.

Figure 5: Toggling the Timebase button (outlined in orange) to Seconds locks the markers to minutes and seconds.

Name the Markers after the Events that need to conform to a hit point. If the tempo changes, move the Events to line up with their associated Markers.

I hope that at least one of these tips can help you save a session!

The Ultimate Creative Block Unlock

By Craig Anderton

You’ve probably seen ads for packs of MIDI chords that claim to help you write hits that will make your listeners’ jaws drop in amazement as they bask in the awesomeness of your musical talent. But save your money—Studio One’s Chord Track is a fantastic way to help sketch out songs, as well as smash creative blocks. Best of all, you don’t need to understand music theory like chords, harmonies, and intervals. All you need is ears and the ability to say “I like that” or “I don’t like that, so I’ll try something else.” Let’s explore one way to have the Chord Track work for you.

Setup

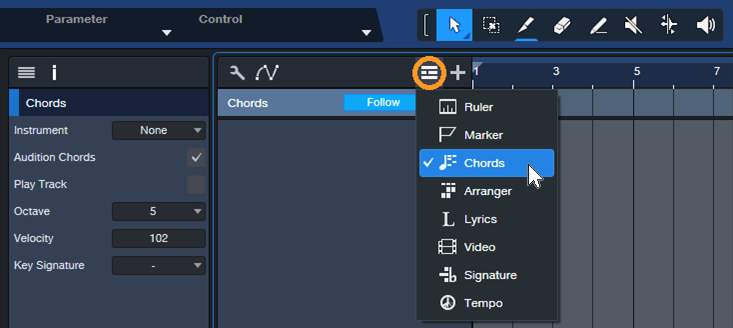

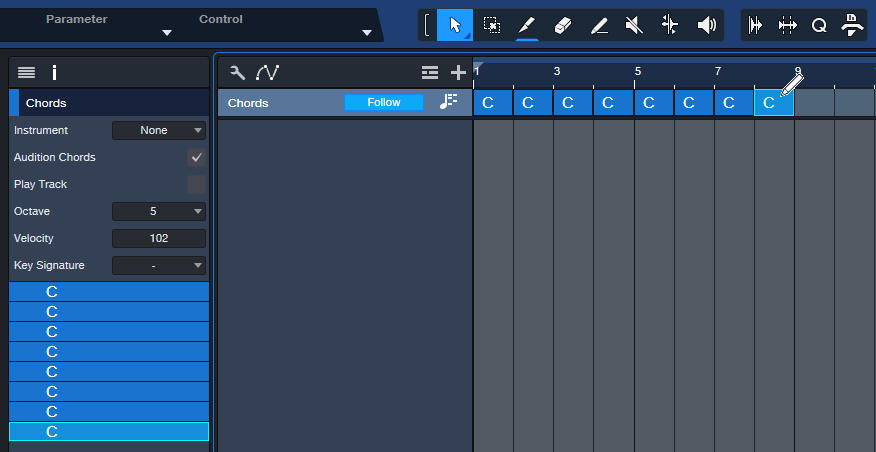

1. Create a new Song, and open the Chord track (fig. 1).

Figure 1: Click on the icon circled in orange and then choose Chords.

2. Choose the Paint tool. The goal is to fill the Chord Track with 1 measure chords. Click in each measure with the Paint tool to enter a C major chord (fig. 2). Tip: You can copy and paste the chords to fill the Chord Track faster.

Figure 2: The Paint tool is entering a C chord. The Chord Track’s Inspector shows the chords that have been entered.

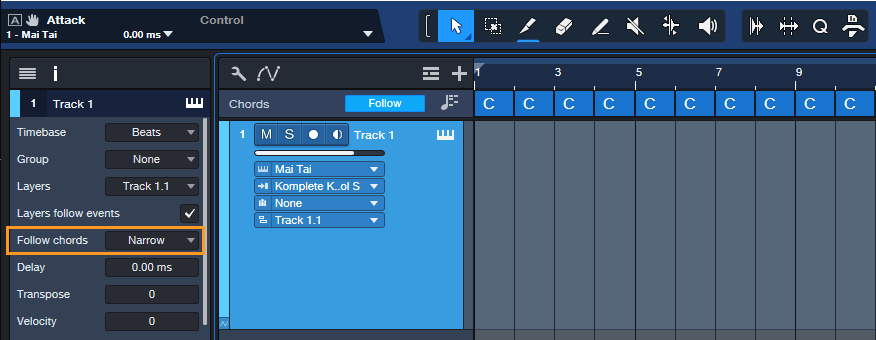

3. Insert an Instrument, like Mai Tai. This will be the playback engine for the chord progressions you create. Then, hit F4 to open the instrument’s Inspector and choose “Narrow” for Follow Chords (fig. 3).

Figure 3: After entering an instrument to play the chords, choose Narrow for the Inspector’s Follow Chords parameter. Also try the Parallel follow mode at some point, which gives different voicings.

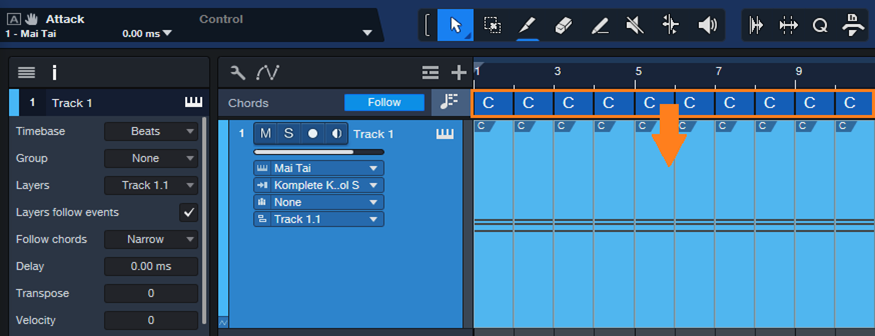

4. Drag the chords from the Chord Track into the Instrument track. Now each measure has a C major chord in it (fig. 4).

Figure 5: Drag the chords into the Instrument track to create MIDI data that corresponds to the chords.

Playing with Chords

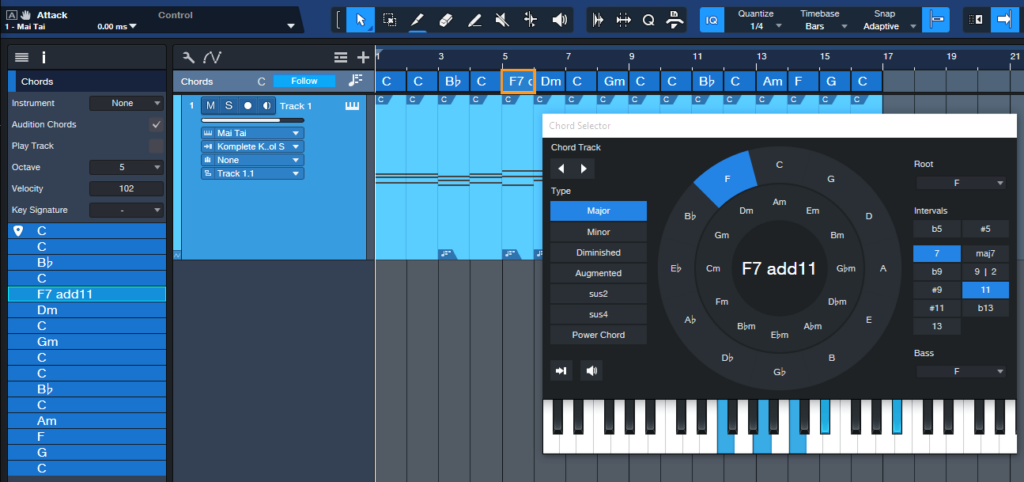

Now we can play around with chord progressions.

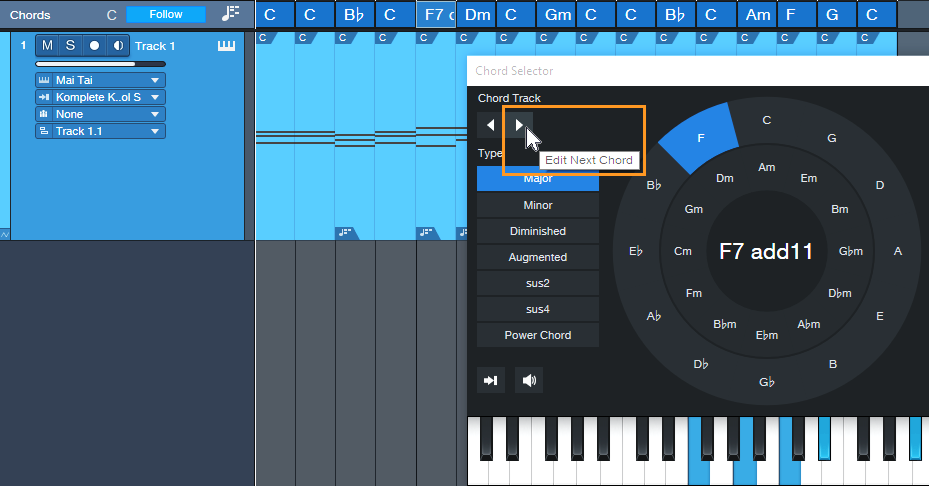

5. Double-click on a chord in the Chord Track. When the Chord Selector opens, click on a chord. Fig. 5 shows adding an F Major 7 with an added 11th at the 5th measure. Note that you don’t need to know any theory, just click on options and see if you like the way they sound. And even if you do know theory, clicking around in a spirit of experimentation can free you from creative ruts.

Figure 5: A C major chord is being replaced with an F7 Major Chord that includes an added 11th interval.

6. To move to the next chord, click on the Edit Next Chord arrow (fig. 6). The arrow to its left moves you to the previous chord. You can also modify any chord in the Chord Track just by double-clicking on it. After selecting the chord to edit, click on a new chord from the Chord Selector. Then, play back the progression to hear if you like the new chord. If not, choose a different one.

Figure 6: You can navigate through the chord progression by using the next/previous chord arrows.

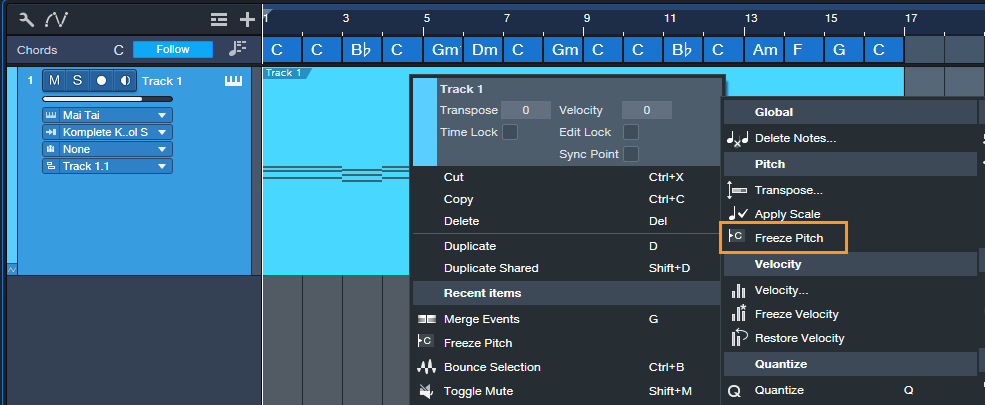

7. Although the Instrument track notes show the chords from the Chord Track, the underlying notes remain the C major chords that were placed originally. To finalize your progression, select all the measures of MIDI notes, then type G to merge them into a single Event. Next, right-click on the Event and choose Musical Functions > Freeze Pitch (fig. 7). In the Inspector, turn off Follow Chords as it’s not needed anymore. The chord changes are now permanent.

Figure 7: Freezing pitch preserves the Note Event pitches created by the Chord Track.

Additional Tips

- A measure might be too long for a chord change you want. If so, use the Split tool to create a shorter chord by splitting an existing chord. Split the Instrument track in the same place, so that the Event is the same duration as the shorter chord. Now you can change the shortened chord.

- The Chord Selector isn’t limited to major and minor chords. It has multiple chord types (diminished, augmented, etc.) as well as additional intervals if you want, for example, a G Major 6 instead of a standard G Major.

- If you’re a fan of crazy atonal chords, no problem. While the Chord Selector is open for a particular chord, click on any of the Chord Selector keyboard’s notes to add them to the chord.