Mixing à la Studio One

Ask 100 recording engineers about their approach to mixing, and you’ll hear 100 different answers. Here’s mine, and how this approach relates to Studio One.

The Mix Is Not a Recording’s Most Important Aspect

If it was, recordings from the past with a primitive, unpolished sound wouldn’t have endured to this day. The most important aspect is tracking—the mix provides a home for the tracks. If you capture stellar instrument and vocal sounds, the mix will almost take care of itself. Granted, you can fix sounds in the mix. But because each track interacts with the other tracks to create the mix, changing any track changes its interactions with all the other tracks. If multiple tracks require major fixes, the mix may start to fall apart as different fixes conflict with each other.

So, a great mix starts with inspired tracks. When tracking and working with MIDI, enable Retrospective Recording (Preferences or Options, then Advanced/MIDI/Enable retrospective recording). If you play some dazzling MIDI part but hadn’t pressed record, no worries—Studio One will have stored what you played. For audio, create a template that lets you track audio quickly, before inspiration dissipates. It’s helpful if your audio interface has enough inputs so that you can leave your main instruments and mics always patched in. Then, simply record-enable a track, and you’re ready to record.

Start Mixing Without Plugins—But Do Any Needed DSP Fixes

Here’s one reason why you don’t want to start by adding plugins. Sound on Sound did a series called Mix Rescue where the editors would go to a home studio and give tips on how the person working there could obtain a better mix. One time the owner offered the editors some tea, and went into the kitchen to make it. Meanwhile, the SOS folks wanted to hear what the raw tracks sounded like, so they bypassed all the plugins. When the owner came back, his first question was “what did you do to make it sound so much better?” I assume the problem was that the person doing the mix started adding plugins to enhance individual tracks, without remembering the importance of all the tracks working together.

Using DSP to alter levels can optimize tracks, without altering their character the way most plugins do. For more consistent levels, particularly with vocals, use Gain Envelopes and/or selective normalizing. (Note that you can normalize Events in the Inspector.) Also, cut spaces between phrases to delete any residual noise. Edit tracks to remove sections that you may like, but don’t advance the song’s storyline. Then, the remaining parts will have more prominence.

My one exception to “no plugins at first” is if the plugins are essential to the final sound. For example, a guitar part may require an amp sim. Or, a synth arpeggio may require a dotted eighth-note delay when it’s part of the song’s rhythm section.

Obtain the Best Possible Balance of Your Tracks

While you work on the mix without plugins, get to know the song’s feel and the global context for the tracks. As you mix, you may hear sounds you want to fix. Avoid that temptation for now—keep trying to achieve the best possible balance until you can’t improve the balance any further. Personal bias alert: The more plugins you add to a track, the more they obscure the underlying sound. Sometimes this is good, sometimes it isn’t. But when mixing with a minimalist approach, you can always make additions later. If you make additions early on, they may not make sense in the context of changes that occur as you build toward the final mix.

Here’s another personal bias alert: Avoid using any master bus plugins until you’re ready to master your mix. Although master bus plugins can put a band-aid on problems while you mix, those underlying problems remain. I believe that if you aim for the best possible mix without any master bus plugins, then when you do add master bus plugins in the Project page to enhance the sound, they’ll make a great mix outstanding.

This way of working is unlike the “top-down” mixing technique that advocates mixing with master bus processors from the start. Proponents say that this not only encourages listening to the mix as a finished product, but since you’ll add master bus processors eventually, you might as well mix with them already in place. However, most top-down mixes still undergo mastering, so bus processors then become part of mixing and mastering. If that approach works for you, great! But my best mixes have separated mixing and mastering into two distinct processes. Mixing is about creating a balance among tracks. Mastering is about enhancing that balance into a refined, cohesive whole.

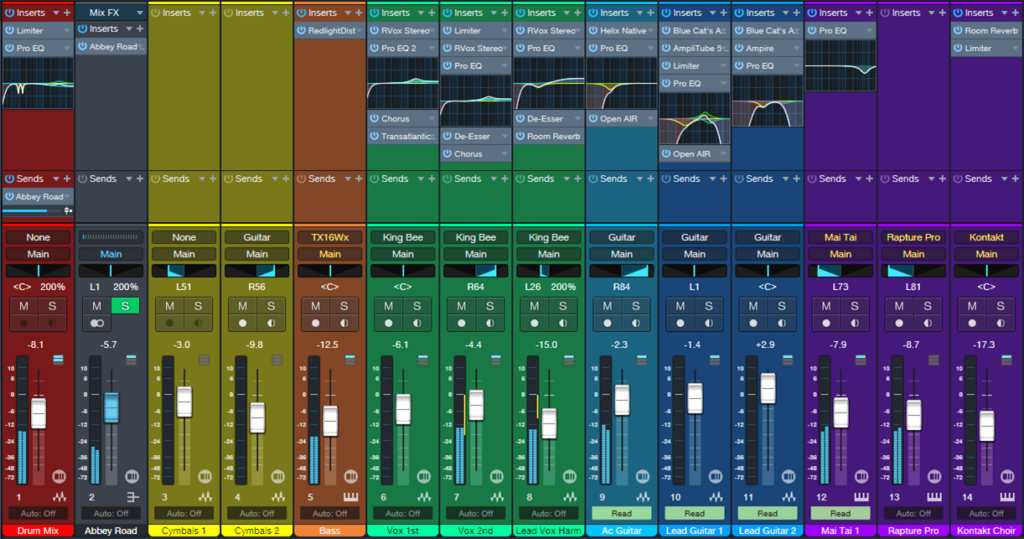

EQ Tracks Strategically

By now, mixing without plugins has established the song’s character. Next, it’s time to shift your focus from the forest to the trees. Identify problem areas where the tracks don’t quite gel. Use the Pro EQ to carve out sonic spaces for the tracks (fig. 1), so they don’t conflict with each other. For example, suppose the lower mids sound muddy, even though the balance sounds correct. Solo individual tracks until you identify the one that’s contributing the most “mud.” Then, use EQ to reduce its lower midrange a bit. Or, a vocal might have to be overly loud to be intelligible. In this case, a slight upper midrange boost can increase intelligibility without needing to raise the track’s overall level.

If a static boost or cut seems heavy-handed, the Pro EQ3’s dynamic equalization function introduces EQ only when needed, based on the audio’s dynamics. For more info, see the blog post Plug-In Matrimony: Pro EQ3 Weds Dynamics.

Some engineers like using a highpass filter on tracks that don’t have low-frequency energy anyway. Use the Pro EQ’s linear-phase stage, and then before adding any other effects to the track, render it to save CPU power. Traditional minimal-phase EQ can introduce phase shifts above the cutoff frequency.

Implement Needed Dynamics Control

Using EQ to help differentiate instruments means you may not need much dynamics processing. For example, after using EQ to make the vocals more intelligible, they might benefit more from light limiting than heavy compression. A little saturation on bass will give a higher average level, reduce peaks, and add harmonics. These enhancements allow the bass to stand out more without using conventional dynamics processors, or having to increase its level to where it conflicts with other instruments.

Be sparing with dynamics processing, at least initially. Mastering most pop/EDM/rock/country music involves using compression or limiting. This keeps the level in the same range as other songs that use master bus processing, and helps “glue” the tracks together. But remember, master bus processors—whether compression, EQ, maximization, or whatever—apply that processing to every track. If you’ve already done a lot of dynamics processing to individual tracks, adding more processing with mastering plugins could end up being excessive. (To be fair, this is a valid argument for top-down mixing. It’s not my preference, but it’s a technique that could work well for you.)

Studio One has the unique ability to jump between the mastering page and its associated multitrack projects. (I’m astonished that no other DAW has stolen—I mean, been inspired by—this architecture.) If after adding processors in the mastering page you decide individual tracks need changes to their amounts of dynamics processing, that’s easy to do.

Ear Candy: The Final Frontier

Now you have a clean,integratedmix that does justice to the vision you had when tracking the music. Keep an open mind about whether any little production touches could make it even better—an echo that spills over, an abrupt mute, a slight tempo change to help the song breathe (although it’s often best to apply this to the rendered stereo mix, prior to mastering), a tweak of a track’s stereo image—these can add those extra “somethings” that make a mix even more compelling.

Mastering

Mastering deserves its own blog post, because it involves a lot more than just slamming a maximizer on the output bus. If this post gets a good response, I’ll do a follow up on mastering.