Tag Archives: How to Studio One

Pro EQ2: More than Just a Facelift

Yes, Studio One 5’s Pro EQ2 has a more “pro” look…but there are also some major improvements under the hood, so let’s investigate.

Linear-Phase Low-Cut Filter

This is arguably the most significant change, and appears as an eighth filter stage just below the left of the frequency response display (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: The phase-linear Low-Cut filter section offers three cutoff frequencies and two different slopes.

There’s much mythology around linear-phase EQ, so here are the basics. Traditional EQ introduces phase shifts when you boost or cut. With multiple EQ stages, these phase differences can produce subtle cancellations or reinforcements at particular frequencies. This may or may not create a sometimes subtle, sometimes obvious effect called “smearing.” However, it’s important to note that these phase shifts also give particular EQs their “character” and therefore, can be desirable.

Linear-phase EQ technology delays the signal where appropriate so that all bands are in phase with each other. This tends to give a more “transparent” sound. You might wonder why there’s only one linear-phase stage, with a low-cut response, but there’s a good reason for this. Many engineers like to remove unneeded low frequencies for utilitarian purposes (e.g., remove p-pops or handling noise from vocals), or for artistic reasons, like reducing lows on an amp sim cab to emulate more of an open-back cab sound. Standard EQ introduces phase changes above the cutoff frequency; with linear-phase EQ, there are no phase issues. This can be particularly important with doubled audio sources, where you don’t want phase differences between them due to slightly different EQ settings.

The Pro EQ2 is very efficient, but note that enabling linear-phase EQ requires far more CPU power, and adds considerable latency—it’s not something you’ll want to add to every track. Fortunately, in many cases, it’s a setting that you apply and don’t think about anymore. This makes it a good candidate for “Transform to Rendered Audio” so you can reclaim that CPU power, and then use conventional EQ going forward.

By the way, an argument against linear-phase EQ is that it can create pre-ringing, which adds a low-level, “swooshing” artifact before audio transients. Fortunately, it’s a non-issue here, because pre-ringing is audible only at low frequencies, with high gain and Q settings. (Note that traditional EQ can add post-ringing, although you usually won’t hear it because the audio masks it.)

Level Range Options

I’ve wanted this feature for a long time. Some EQ changes are extremely subtle, particularly when mastering. With range set to 24 dB, it’s difficult to drag nodes around precisely. What’s more, when making fine gain changes, with the 24 dB view it’s easy to move slightly to the right or left, and end up editing frequency instead. Holding Shift provides fine-tuning, but for fast EQ adjustments, the 6 dB view is welcome (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: It’s much easier to see subtle EQ changes by setting the level range to 6 dB.

Granted, you adjust EQ with your ears, not your eyes—but learning how to correlate sound to frequency is important. I knew one guitar player who when he said something like “that track really needs to come down about 2.5 dB at 1.25 kHz,” he was 100% spot-on. When mixing, he could zero in on EQ settings really fast.

And there’s another implication. Those learning how to use EQ often overcompensate, so at seminars, I advise applying what I call “the rule of half”: if you think a sound needs 6 dB of boost, try 3 dB of boost instead and get acclimated to it before adding more boost. If you choose the 6 dB view, you’ll be forced to use smaller boost and cuts in order to adjust or see them graphically—and you might find those smaller changes are all you need.

12th Octave Frequency Response Display

The Third-Octave Display is good eye candy, and gives a rough idea of how EQ affects the sound. The new 12th-Octave resolution option gives far better definition. In Fig. 3, note how many of the peaks and dips visible in the 12th-Octave display are averaged out, and lost, in the Third-Octave version.

Figure 3: The 12th-Octave display in the lower view gives far greater detail and resolution.

Workflow Improvements

In addition to the more “marquee” improvements, several other additions make working with Pro EQ2 a better experience than the original Pro EQ.

Keyboard Display. Now you can correlate frequency to note pitches; note that these line up with the bars in the 12th-octave display.

Band Controls. In Studio One 4, there was a little, almost invisible arrow between the controls and the frequency response display. Clicking on this hid the controls. The Band Controls button does the same thing, and you won’t overlook it.

Curves Button. Similarly, Studio One 4’s All/Current buttons that control how curves are displayed have been consolidated into a single Curves button.

Sidechaining. We already covered Pro EQ sidechaining in the blog post The Sidechained Spectrum. However, when choosing the FFT curve, now there’s a sidechain spectrum peak hold button for the sidechain input. Clicking on the “snowflake” button freezes peaks (hence the name) until you click the button again.

Better Metering. Studio One 4’s Pro EQ had only output metering, whereas Pro EQ2 has metering for both input and output. This is a highly useful addition. If the output is too hot, you can always turn down the output level, but you won’t know if the reason why it’s hot is because you’ve boosted some frequencies too much, or the input level is hitting the EQ too hard. Now you’ll know. As with Studio One 4, the metering shows both peak and average levels.

And that’s a wrap for Pro EQ2. I guess you could say the newer version is ahead of the curve…the EQ curve, that is ?

Rockin’ Rhythms with Multiband Gating

We’ve covered multiband processing before, but now it’s time for something different: multiband gating.

You send a drum or percussion track to three buses, each with an EQ covering a different frequency range—e.g., kick, snare, and cymbals. These provide three control signals…and here’s what we do with them.

A guitar track feeds an FX Chain with Ampire, which goes into a Splitter that splits by frequency. There’s a gate in each split, and they’re driven by the control signals. So when the kick hits, the guitar’s low frequencies come through. When snare and upper toms hit, the mids come through and when there are high-frequency sounds like percussion, they trigger the highs. You can think of the effect as similar to a mini-vocoder.

The audio example has some Brazilian rhythms triggering the gates, and you can hear the kind of animation this technique adds to the guitar part. The first four measures have the drums mixed with the processed guitar, while the second four measures are processed guitar only.

SETTING IT UP

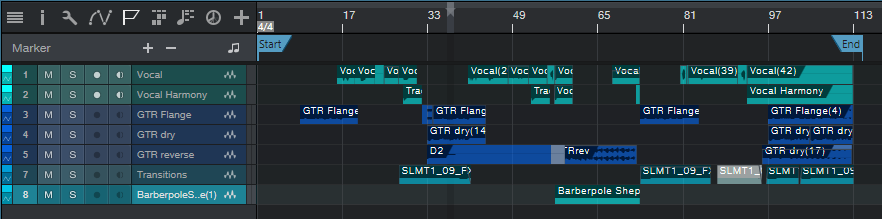

Fig. 1: The track layout for multiband gating.

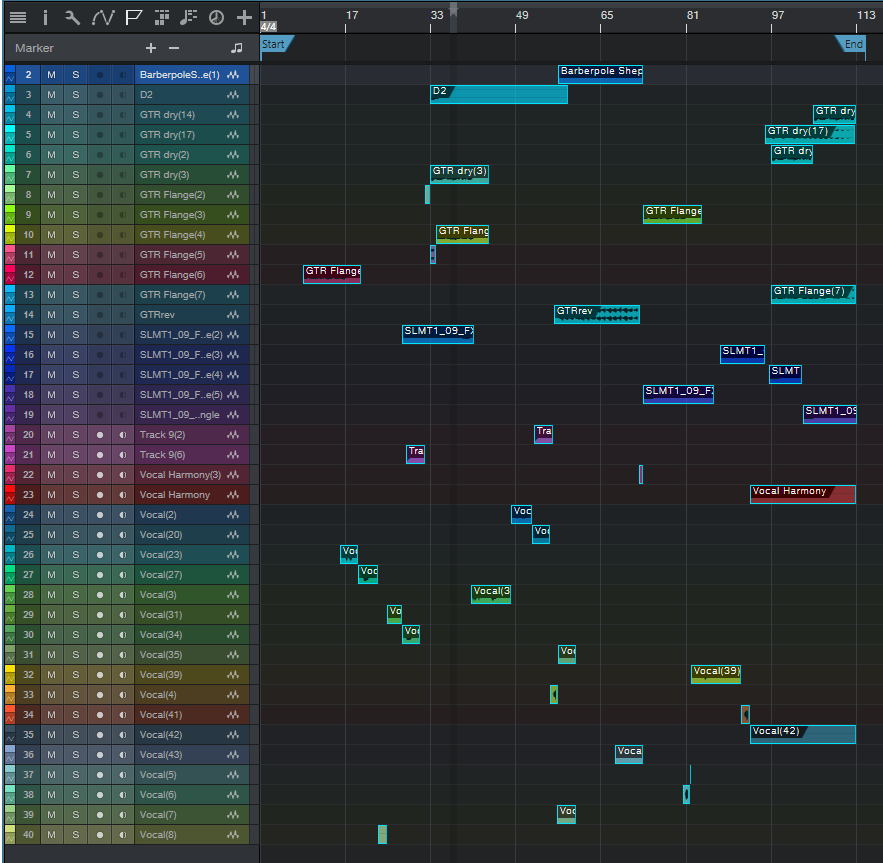

The Drums track has three pre-fader sends, which go to the Lo, Mid, and Hi frequency buses. Each bus has a Pro EQ to emphasize the desired low, mid, and high frequencies. Then, each bus has a send that goes to its associated Gate sidechain in the Guitar track (Fig. 2).

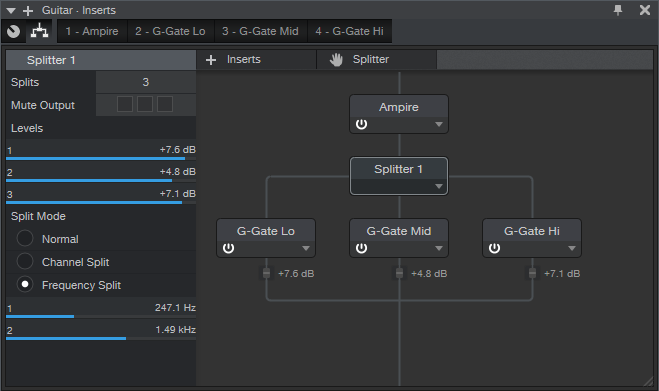

Fig. 2: Splitter and Gate setup for multiband gating.

The guitar goes to Ampire, which splits into three frequencies bands thanks ot the Splitter’s Frequency Split magical powers. Each split goes to a Gate, and the sends from the Lo, Mid, and Hi buses feed their respective gate sidechains.

Inserting a Dual Pan after the Mid and Hi gates can enhance the sound further, by spreading these frequencies a bit to the left or right to give more of a stereo spread. You’ll probably want to keep the low frequencies centered.

You don’t have to get too precise about tuning the EQs in the buses, or setting the Splitter frequencies. I set up the Splitter frequencies by playing guitar through the Splitter, and adjusting the bands so that the guitar’s various frequency ranges seemed balanced. As for the Pro EQs in the buses, I just tuned those to the drum sounds until the guitar rhythm was rockin’ along.

This takes a little effort to set up, but multiband gating can add a unique rhythmic kick to your music. Interestingly, you may also find that you don’t need as much instrumentation when one of them is blurring the line between melody and rhythm.

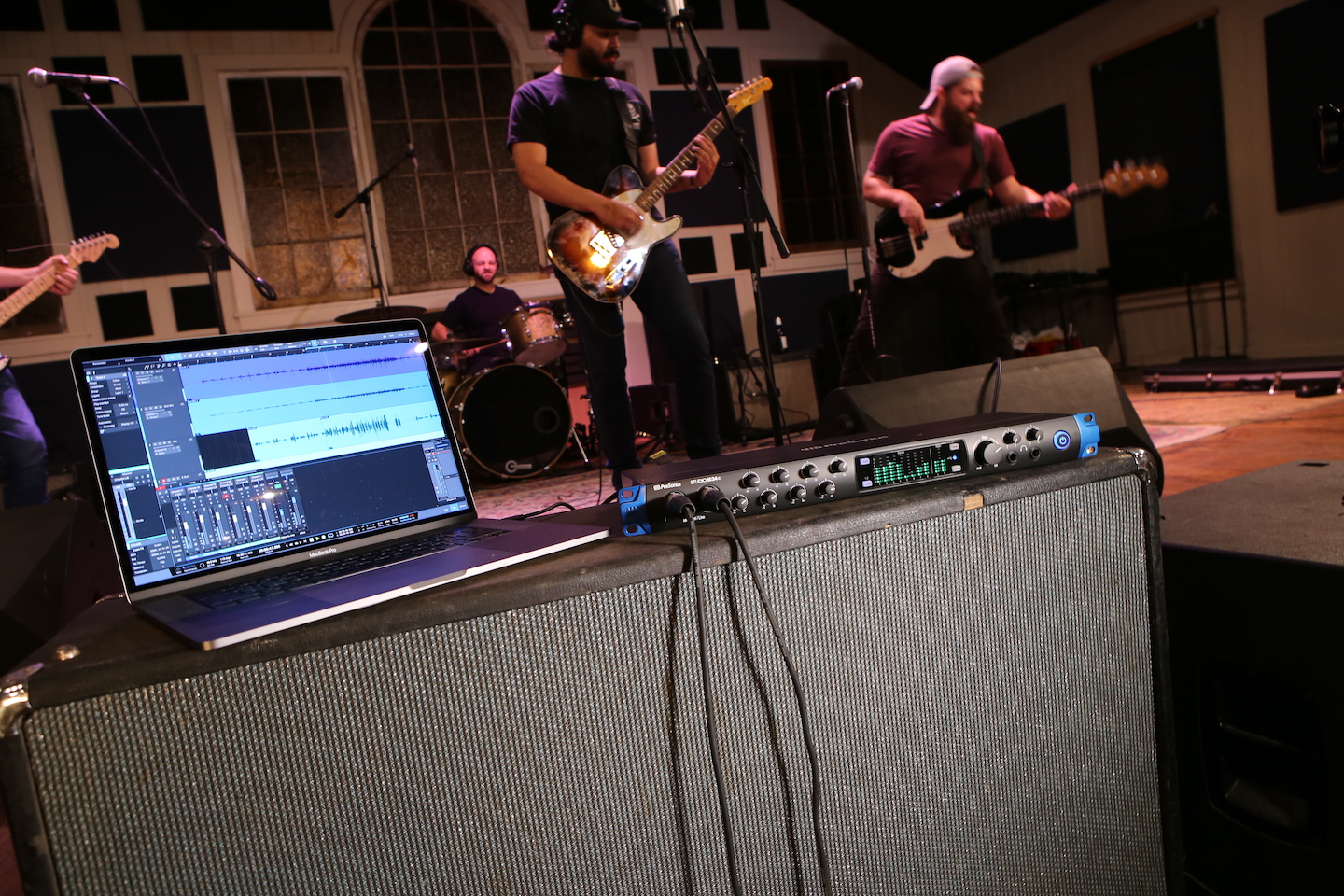

Craig Anderton’s Big Book Round-Up

If you’ve spent a couple of spare evenings at home poking around the web for tips on music and audio production, it’s really very likely that you’ve run into some posts, articles, or comments from Craig Anderton. In fact, you may have had to update your search criteria to sort by “most recent,” because it’s fairly common for Google to show you some Craig Anderton posts from the dawn of the internet age, which—while cool—may not be particularly full of insight on Studio One version 4.

Fact is Craig is our industry’s most acclaimed writers, and he’s spoken about Studio One in-person at more events than I can count, and is of course responsible for the Friday Tips section of this very blog. In short, Craig’s contributions to the success and proliferation of Studio One can’t really be counted.

But his Studio One books? Those can be counted. There are five.

We wanted to take a minute to thank Craig for all of his hard work, broadly-reaching creative output, and continued support of PreSonus and Studio One. Let’s take a closer look at what he’s got over at shop.presonus.com. Chances are one or more of these will prove valuable to you and your process. Note that these are eBooks, not hardcover books, and will be downloaded as PDFs.

How to Record and Mix Great Guitar Sounds in Studio One

Essential reading for anyone who records guitars in Studio One, this definitive book covers invaluable production and engineering techniques.

- 274-page, beautifully-illustrated eBook is the fifth book in this acclaimed series of how to get the absolute most out of Studio One

- Covers all aspects of recording and mixing guitar, from how to choose the right strings for a particular tone, to advanced techniques that bring out the best in amp modeling plug-ins

- Applicable to all genres, from acoustic folk to heavy metal

- Links from contents page to topics—find specific subjects quickly

- Find out how to use DSP, effects, real-time control, and much more

The Big Book of Studio One Tips and Tricks

The Big Book of Studio One Tips and Tricks

Consolidates, updates, expands on, and categorizes 130 tips from Craig’s popular “Friday Tip of the Week” blog posts that you probably have been checking out right here. Essential reading. This massive book includes tips on how solve problems, enhance sound quality, improve workflow, achieve greater expressiveness, create signature sounds, and much more.

- 289 pages with 278 four-color illustrations to help streamline the learning process

- Includes 39 free presets (28 Multipresets, 10 Mai Tai presets, 1 Presence XT preset) that support the tips

How to Create Compelling Mixes in Studio One

How to Create Compelling Mixes in Studio One

A comprehensive, practical, and above all inspiring guide on how to use Studio One’s sophisticated toolset to craft the perfect mix.

- 258-page eBook with over 180 four-color illustrations

- Downloadable PDF format, with links from the contents to book topics

- “Key Takeaways” section for each chapter summarizes chapter highlights

- “Tech Talk” sidebars do deep dives into selected topics

- Covers all aspects of mixing with Studio One

More than Compressors: The Complete Guide to Dynamics in Studio One

More than Compressors: The Complete Guide to Dynamics in Studio One

The ultimate guide to becoming an expert on Studio One’s dynamics processors and dynamics-oriented features.

- 258-page eBook with over 180 four-color illustrations

- Downloadable PDF format, with links from the contents to book topics

- “Key Takeaways” section for each chapter summarizes chapter highlights

- “Tech Talk” sidebars do deep dives into selected topics

- Covers all aspects of mixing with Studio One

How to Record and Mix Great Vocals in Studio One

How to Record and Mix Great Vocals in Studio One

The ultimate guide to capturing, producing, and mixing superb vocal performances in Studio One.

- Profusely illustrated, 121-page eBook

- Covers everything from microphones to the final mix

- Tips on creating compelling vocal performances

- Links from contents page to topics

- Filled with practical, real-world examples

SuperKick—Tune and Enhance Your Kick Drum

If you do hip-hop or EDM, you’re in the right place.

This tip turns wimpy kicks into superkicks, using a different technique compared to drum replacement (see the Friday Tip for February 9, 2018). Listen to the audio example, and you’ll hear why this is cool.

Audio Example: The second four measures add the SuperKick effect to the loop in the first four measures. The added kick is 40 Hz…so don’t expect to hear anything on laptop speakers!

The basic concept is to add another track with a low-frequency sine wave, tuned to your pitch of choice. This can be a WAV file, but this example uses the highly-underrated, and extremely useful, Tone Generator plug-in set to a floor-shaking 40 Hz sine wave. A Bus “listens” to the loop, and uses EQ to filter out everything except the kick; you don’t hear this audio, but it gates the Tone Generator’s sine wave so that it tracks the kick. Fig. 1 shows the setup.

Figure 1: Setup to tune and enhance the kick in an existing loop.

- Track 1 is your drum loop; the audio example uses the Warehouse Tech Musicloop included in Studio One. Insert a pre-fader Send that goes to a Bus (named “EQ Bus” in this example). The reason for a pre-fader send is you’ll want to turn the Track fader down when tweaking the EQ and Gate responses covered later.

- Insert the Pro EQ into the EQ Bus. Tweak the response to filter out everything but the kick. The High Cut’s 48 dB/octave slope will probably do the job, although if there’s a lot of other bass action (like floor toms or bass) you may need to add an additional Peaking stage. Zero in on the kick’s lowest audible frequency, and apply a narrow boost.

- Add a Track, and insert the Tone Generator. Turn it on, then set it to produce a constant, low-frequency sine wave. Follow the tone Generator with a Gate.

- Add a pre-fader send from the EQ Bus to the Gate’s sidechain.

- To produce the most reliable triggering, the Gate settings and the Send level going to the Gate’s sidechain are crucial. Set the Threshold Close just slightly lower than the Open setting. Release determines how long the kick will last; 5 to 10 ms of hold minimizes “chattering.” Start by setting the Open and Threshold controls as shown, and adjust the Send to the sidechain for the most reliable triggering. If the kick tone doesn’t trigger, even with the Send to the sidechain turned up, lower the Open and Threshold close controls. If the kick tone stays on all the time, lower the Send level.

With the loop fader down so you’re not distracted, play with the Tone Generator frequency, EQ frequency to isolate the kick sound, and Gate settings until there’s reliable kick triggering. How you set the gate provides various options: extend the Release for a “hum drum” effect, or for more expressiveness, automate the release time. Increasing the Hold time alters the character as well.=

And after everything is set up…stand back while the floors shake!

The De-Stresser FX Chain

Feeling a little bit stressed?

I’m not surprised. Or do you ever have one of those days? Of course you do! Wouldn’t it be great to go down to the beach, listen to the waves for a while, and chill to those soothing sounds? The only problem for me is that going to the beach would involve a 7-hour drive.

Hence the De-Stresser FX Chain, which doesn’t sound exactly like the ocean—but emulates its desirable sonic effects. If you’re already stressed out, then you probably don’t want to take the time to assemble this chain, so feel free to go to the download link. Load the FX Chain into a channel, but note that you must enable input monitoring, because the sound source is the plug-in Tone Generator’s white noise option.

About the FX Chain

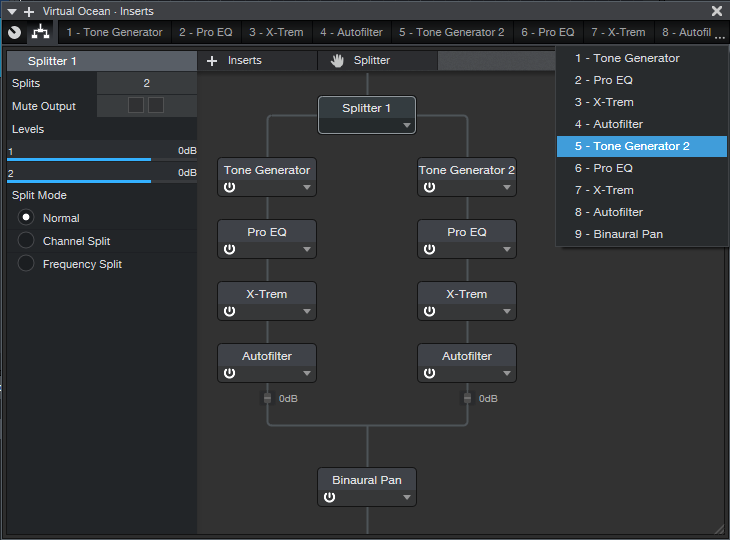

Figure 1: Effects used to create the De-Stresser’s virtual ocean.

Fig. 1 shows the FX Chain’s “block diagram.” The Splitter adds variety to the overall sound by feeding dual asynchronous “waves,” as generated by the X-Trems (set for tremolo mode). The X-Trem LFO’s lowest rate is 0.10 Hz; this should be slow enough, but for even slower waves, you can sync to tempo with a long note value, and set a really slow tempo.

Waves also have a little filtering as they break on the beach, which the Autofilters provide. The Pro EQs tailor the low- and high-frequency content to alter the waves’ apparent size and distance.

And of course, there’s the ever-popular Binaural Pan at the end. This helps create a more realistic stereo image when listening on headphones.

Macro Controls

Figure 2: The Macro Controls panel.

Regarding the Macro Controls panel (Fig. 2), the two Timbre controls alter the filter type for the two Autofilters. This provides additional variety, so choose whichever filter type combination you prefer. Crest alters the X-Trem depth, so higher values increase the difference between the waves’ peaks and troughs.

The Sci-Fi Ocean control adds resonance to the filtering. This isn’t designed to enhance the realism, but it’s kinda fun. Another subtle sci-fi sound involves setting the two Timbre controls to the Comb response.

As you move further away from real waves, the sound has fewer high frequencies. So, Distance controls the Pro EQ HC (High Cut) filters. Similarly, Wave Size controls the LC filter, because bigger waves have more of a low-frequency component. The Calmer control varies the Autofilter mix; turning it up gives smaller, shallower waves.

When you want to relax, this makes a soothing background. Put on good headphones, and you can lose yourself in the sound. It also makes a relaxing environmental sound when played over speakers at a low level. If your computer has Bluetooth, and you have Bluetooth speakers, try playing this in the background at the end of a long day.

Son of the Beach

This is just one example of the kind of environmental sounds and effects you can make with Studio One, so let me know if this type of tip interests you. I’ve also done rain, rocket engines, howling gales, the engine room of an interstellar cargo ship, cosmic thuds, various soundscapes, and even backgrounds designed to encourage theta and delta brain waves. I made the last one originally for a friend of mine whose children had a hard time going to sleep, and burned it to CD. When I asked what he thought, he said “no one has ever heard how it ends.” So I guess it worked! Chalk up another unusual Studio One application.

Download the De-Stresser FX Chain here!

Into the Archives, Part 2

After last week’s thrilling cliff-hanger about how to preserve your WAV files for future generations, let’s look at how to export all your stereo audio tracks and have them incorporate effects processing, automation, level, and panning. There are several ways to do this; although you can drag files into a Browser folder, and choose Wave File with rendered Insert FX, Studio One’s feature to save stems is much easier and also includes any effects added by effects in Bus and FX Channels. (We’ll also look at how to archive Instrument tracks.)

Saving as stems, where you choose individual Tracks or Channels, makes archiving processed files a breeze. For archiving, I choose Tracks because they’re what I’ll want to bring in for a remix. For example, if you’re using an instrument where multiple outputs feed into a stereo mix, Channels will save the mix, but Tracks will render the individual Instrument sounds into their own tracks.

When you export everything as stems, and bring them back into an empty Song, playback will sound exactly like the Song whose stems you exported. However, note that saving as stems does not necessarily preserve the Song’s organization; for example, tracks inside a folder track are rendered as individual tracks, not as part of a folder. I find this preferable anyway. Also, if you just drag the tracks back into an empty song, they’ll be alphabetized by track name. If this is an issue, number each track in the desired order before exporting.

SAVING STEMS

Select Song > Export Stems. Choose whether you want to export what’s represented by Tracks in the Arrange view, or by Channels in the Console. Again, for archiving, I recommend Tracks (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: The Song > Export Stems option is your friend.

If there’s anything you don’t want to save, uncheck the box next to the track name. Muted tracks are unchecked by default, but if you check them, the tracks are exported properly, and open unmuted.

Note that if an audio track is being sent to effects in a Bus or FX Channel, the exported track will include any added effects. Basically, you’ll save whatever you would hear with Solo enabled. In the Arrange view, each track is soloed as it’s rendered, so you can monitor the archiving progress as it occurs.

In Part 1 on saving raw WAV files, we noted that different approaches required different amounts of storage space. Saving stems requires the most amount of storage space because it saves all tracks from start to end (or whatever area in the timeline you select), even if a track-only has a few seconds of audio in it. However, this also means that the tracks are suitable for importing into programs that don’t recognize Broadcast WAV Files. Start all tracks from the beginning of a song, or at least from the same start point, and they’ll all sync up properly.

WHAT ABOUT THE MAIN FADER SETTINGS?

Note that the tracks will be affected by your Main fader inserts and processing, including any volume automation that creates a fadeout. I don’t use processors in the Main channel inserts, because I reserve any stereo 2-track processing for the Project page (hey, it’s Studio One—we have the technology!). I’d recommend bypassing any Main channel effects, because if you’re going to use archived files for a remix, you probably don’t want to be locked in to any processing applied to the stereo mix. I also prefer to disable automation Read for volume levels, because the fade may need to last longer with a remix. Keep your options open.

However, the Main fader is useful if you try to save the stems and get an indication that clipping has occurred. Reduce the Main fader by slightly more than the amount of clipping (e.g., if the warning says a file was 1 dB over, lower the Main channel fader by -1.1 dB). Another option would be to isolate the track(s) causing the clipping and reduce their levels; but reducing the Main channel fader maintains the proportional level of the mixed tracks.

SAVING INSTRUMENT AUDIO

Saving an Instrument track as a stem automatically renders it into audio. While that’s very convenient, you have other options.

When you drag an Instrument track’s Event to the Browser, you can save it as a Standard MIDI File (.mid) or as a Musicloop feature (press Shift to select between the two). Think of a Musicloop, a unique Studio One feature, as an Instrument track “channel strip”—when you bring it back into a project, it creates a Channel in the mixer, includes any Insert effects, zeroes the Channel fader, and incorporates the soft synth so you can edit it. Of course, if you’re collaborating with someone who doesn’t have the same soft synth or insert effects, they won’t be available (that’s another reason to stay in the Studio One ecosystem when collaborating if at all possible). But, you’ll still have the note events in a track.

There are three cautions when exporting Instrument track Parts as Musicloops or MIDI files.

- The Instrument track Parts are exported as MIDI files, which aren’t (yet) time-stamped similarly to Broadcast WAV Files. Therefore, the first event starts at the song’s beginning, regardless of where it occurs in the Song.

- Mutes aren’t recognized, so the file you bring back will include any muted notes.

- If there are multiple Instrument Parts in a track, you can drag them into the Browser and save them as a Musicloop. However, this will save a Musicloop for each Part. You can bring them all into the same track, one a time, but then you have to place them properly. If you bring them all in at once, they’ll create as many Channels/Tracks as there are Instrument Parts, and all Parts will start at the Song’s beginning…not very friendly.

The bottom line: Before exporting an Instrument track as a Musicloop or MIDI file, I recommend deleting any muted Parts, selecting all Instrument Parts by typing G to create a single Part, then extending the Part’s start to the Song’s beginning (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: The bottom track has prepped the top track to make it stem-export-friendly.

You can make sure that Instrument tracks import into the Song in the desired placement, by using Transform to Audio Track. As mentioned above, it’s best to delete unmuted sections, and type G to make multiple Parts into a single Part. However, you don’t need to extend the track’s beginning.

- Right-click in the track’s header, and select Transform to Audio Track.

- Drag the resulting audio file into the Browser. Now, the file is a standard Broadcast WAV Format file.

- When you drag the file into a Song, select it and choose Edit > Move to Origin to place it properly on the timeline.

However, unlike a Musicloop, this is only an audio file. When you bring it into a song, the resulting Channel does not include the soft synth, insert effects, etc.

Finally…it’s a good idea to save any presets used in your various virtual instruments into the same folder as your archived tracks. You never know…right?

And now you know how to archive your Songs. Next week, we’ll get back to Fun Stuff.

Safety First: Into the Archives, Part 1

I admit it. This is a truly boring topic.

You’re forgiven if you scoot down to something more interesting in this blog, but here’s the deal. I always archive finished projects, because remixing older projects can sometimes give them a second life—for example, I’ve stripped vocals from some songs, and remixed the instrument tracks for video backgrounds. Some have been remixed for other purposes. Some really ancient songs have been remixed because I know more than I did when I mixed them originally.

You can archive to hard drives, SSDs, the cloud…your choice. I prefer Blu-Ray optical media, because it’s more robust than conventional DVDs, has a rated minimum shelf life that will outlive me (at which point my kid can use the discs as coasters), and can be stored in a bank’s safe deposit box.

Superficially, archiving may seem to be the same process as collaboration, because you’re exporting tracks. However, collaboration often occurs during the recording process, and may involve exporting stems—a single track that contains a submix of drums, background vocals, or whatever. Archiving occurs after a song is complete, finished, and mixed. This matters for dealing with details like Event FX and instruments with multiple outputs. By the time I’m doing a final mix, Event FX (and Melodyne pitch correction, which is treated like an Event FX) have been rendered into a file, because I want those edits to be permanent. When collaborating, you might want to not render these edits, in case your collaborator has different ideas of how a track should sound.

With multiple-output instruments, while recording I’m fine with having all the outputs appear over a single channel—but for the final mix, I want each output to be on its own channel for individual processing. Similarly, I want tracks in a Folder track to be exposed and archived individually, not submixed.

So, it’s important to consider why you want to archive, and what you will need in the future. My biggest problem when trying to open really old songs is that some plug-ins may no longer be functional, due to OS incompatibilities, not being installed, being replaced with an update that doesn’t load automatically in place of an older version, different preset formats, etc. Another problem may be some glitch or issue in the audio itself, at which point I need a raw, unprocessed file for fixing the issue before re-applying the processing.

Because I can’t predict exactly what I’ll need years into the future, I have three different archives.

- Save the Studio One Song using Save To a New Folder. This saves only what’s actually used in the Song, not the extraneous files accumulated during the recording process, which will likely trim quite a bit of storage space compared to the original recording. This will be all that many people need, and hopefully, when you open the Song in the future everything will load and sound exactly as it did when it was finished. That means you won’t need to delve into the next two archive options.

- Save each track as a rendered audio WAV file with all the processing added by Studio One (effects, levels, and automation). I put these into a folder called Processed Tracks. Bringing them back into a Song sounds just like the original. They’re useful if in the future, the Song used third-party plug-ins that are no longer compatible or installed—you’ll still have the original track’s sound available.

- Save each track as a raw WAV file. These go into a folder named Raw Tracks. When remixing, you need raw tracks if different processing, fixes, or automation is required. You can also mix and match these with the rendered files—for example, maybe all the rendered virtual instruments are great, but you want different vocal processing.

Exporting Raw Wave Files

In this week’s tip, we’ll look at exporting raw WAV files. We’ll cover exporting files with processing (effects and automation), and exporting virtual instruments as audio, in next week’s tip.

Studio One’s audio files use the Broadcast Wave Format. This format time-stamps a file with its location on the timeline. When using any of the options we’ll describe, raw (unprocessed) audio files are saved with the following characteristics:

- No fader position or panning (files are pre-fader)

- No processing or automation

- Raw files incorporate Event envelopes (i.e., Event gain and fades) as well as any unrendered Event FX, including Melodyne

- Muted Events are saved as silence

Important: When you drag Broadcast WAV Files back into an empty Song, they won’t be aligned to their time stamp. You need to select them all, and choose Edit > Move to Origin.

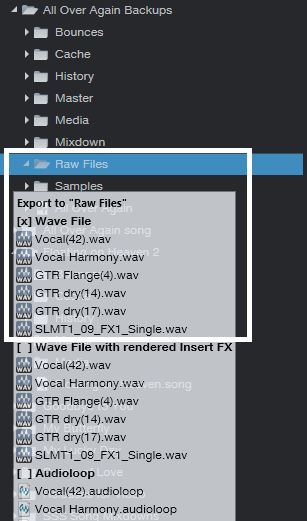

The easiest way to save files is by dragging them into a Browser folder. When the files hover over the Browser folder (Fig. 1), select one of three options—Wave File, Wave File with rendered Insert FX, or Audioloop—by cycling through the three options with the QWERTY keyboard’s Shift key. We’ll be archiving raw WAV files, so choose Wave File for the options we’re covering.

Figure 1: The three file options available when dragging to a folder in the Browser are Wave File, Wave File with rendered Insert FX, or Audioloop.

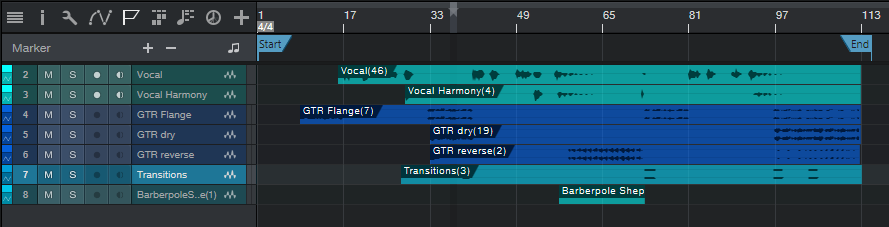

As an example, Fig. 2 shows the basic Song we’ll be archiving. Note that there are multiple Events, and they’re non-contiguous—they’ve been split, muted, etc.

Figure 2: This shows the Events in the Song being archived, for comparison with how they look when saving, or reloading into an empty Song.

Option 1: Fast to prepare, takes up the least storage space, but is a hassle to re-load into an empty Song.

Select all the audio Events in your Song, and then drag them into the Browser’s Raw Tracks folder you created (or whatever you named it). The files take up minimal storage space, because nothing is saved that isn’t data in a Song. However, I don’t recommend this option, because when you drag the stored Events back into a Song, each Event ends up on its own track (Fig. 3). So if a Song has 60 different Events, you’ll have 60 tracks. It takes time to consolidate all the original track Events into their original tracks, and then delete the empty tracks that result from moving so many Events into individual tracks.

Figure 3: These files have all been moved to their origin, so they line up properly on the timeline. However, exporting all audio Events as WAV files makes it time-consuming to reconstruct a Song, especially if the tracks were named ambiguously.

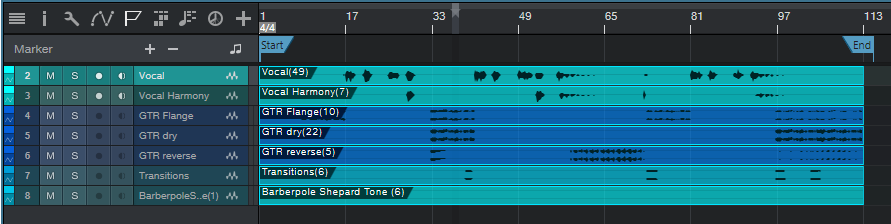

Option 2: Takes more time to prepare, takes up more storage space, but is much easier to load into an empty Song.

- Select the Events in one audio track, and type Ctrl+B to join them together into a single Event in the track. If this causes clipping, you’ll need to reduce the Event gain by the amount that the level is over 0. Repeat this for the other audio tracks.

- Joining each track creates Events that start at the first Event’s start, and end at the last Event’s end. This uses more memory than Option 1 because if two Events are separated by an empty space of several measures, converting them into a single Event now includes the formerly empty space as track data (Fig. 4).

Figure 4: Before archiving, the Events in individual tracks have now been joined into a single track Event by selecting the track’s Events, and typing Ctrl+B.

- Select all the files, and drag them to your “Raw Tracks” folder with the Wave File option selected.

After dragging the files back into an empty Song, select all the files, and then after choosing Edit > Move to Origin, all the files will line up according to their time stamps, and look like they did in Fig. 4. Compare this to Fig. 3, where the individual, non-bounced Events were exported.

Option 3: Universal, fast to prepare, but takes up the most storage space.

When collaborating with someone whose program can’t read Broadcast WAV Files, all imported audio files need to start at the beginning of the Song so that after importing, they’re synched on the timeline. For collaborations it’s more likely you’ll export Stems, as we’ll cover in Part 2, but sometimes the following file type is handy to have around.

- Make sure that at least one audio Event starts at the beginning of the song. If there isn’t one, use the Pencil tool to draw in a blank Event (of any length) that starts at the beginning of any track.

Figure 5: All tracks now consist of a single Event, which starts at the Song’s beginning.

- Select all the Events in all audio tracks, and type Ctrl+B. This bounces all the Events within a track into a single track, extends each track’s beginning to the beginning of the first audio Event, and extends each track’s end to the end of the longest track (Fig. 5). Because the first Event is at the Song’s beginning, all tracks start at the Song’s beginning.

- Select all the Events, and drag them into the Browser’s Raw Tracks folder (again, using the Wave File option).

When you bring them back into an empty Song, they look like Fig. 5. Extending all audio tracks to the beginning and end is why they take up more memory than the previous options. Note that you will probably need to include the tempo when exchanging files with someone using a different program.

To give a rough idea of the memory differences among the three options, here are the results based on a typical song.

Option 1: 302 MB

Option 2: 407 MB

Option 3: 656 MB

You’re not asleep yet? Cool!! In Part 2, we’ll take this further, and conclude the archiving process.

Add Studio One to your workflow today and save 30%!

Tremolo: Why Be Normal?

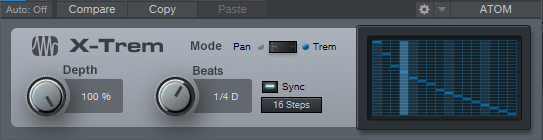

Tremolo (not to be confused with vibrato, which is what Fender amps call tremolo), was big in the 50s and 60s, especially in surf music—so it has a pretty stereotyped sound. But why be normal? Studio One’s X-Trem goes beyond what antique tremolos did, so this week’s Friday Tip delves into the cool rhythmic effects that X-Trem can create.

TREMOLOS IN SERIES

The biggest improvement in today’s tremolos is the sync-to-tempo function. One of my favorite techniques for EDM-type music is to insert two tremolos in series (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: These effects provide the sound in Audio Example 1. Note the automation track, which is varying the first X-Trem’s Depth parameter.

The first X-Trem runs at a fast rate, like 1/16th notes. Square wave modulation works well for this if you want a “chopped” sound, but I usually prefer sine waves, because they give a smoother, more pulsing effect. The second X-Trem runs at a slower rate. For example, if it syncs to half-notes, X-Trem lets through a string of pulses for a half-note, then attenuates the pulses for the next half-note. Using a sine wave for the second tremolo gives a rhythmic, pulsing sound that’s effective on big synth chords—check out the audio example.

BUILD YOUR OWN WAVEFORM

X-Trem’s waveforms are the usual suspects: Triangle, Sine, Upward Sawtooth, and Square. But what if you want a downward sawtooth, a more exponential wave (Fig. 2), or an entirely off-the-wall waveform?

Figure 2: Let’s have a big cheer for X-Trem’s 16 Steps option.

This is where the 16 Steps option becomes the star (Fig. 2) because you can draw pretty much any waveform you want. It’s a particularly effective technique with longer notes because you can hear the changes distinctly.

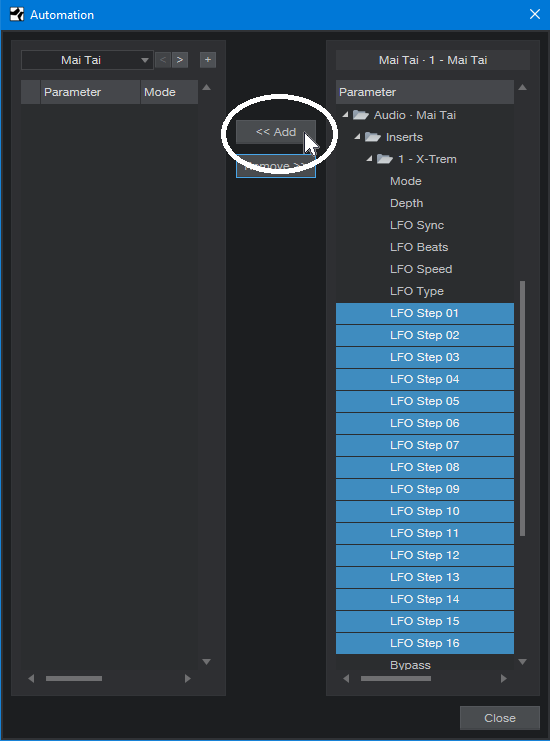

But for me, the coolest part is X-Trem’s “Etch-a-Sketch” mode, because you can automate each step individually, choose X-Trem’s Automation Write, and go crazy. Just unfold X-Trem’s automation options, choose all the steps, add them to the track’s automation, and draw away (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: Drawing automated step changes in real-time takes X-Trem beyond “why be normal” into something that may be illegal in some states.

Of course, if you just draw kind of randomly, then really, all you’re doing is level automation. Where this option really comes into its own is when you have a basic waveform for one section, change a few steps in a different section and let that repeat, draw a different waveform for another section and let that repeat, and so on. Another application is trying out different waveforms as a song plays, and capturing the results as automation. If you particularly like a pattern, cut and paste the automation to use it repetitively.

And just think, we haven’t even gotten into X-Trem’s panning mode—similarly to its overachieving tremolo functions, the panning can do a lot more than just audio ping-pong effects. Hmmm…seems like another Friday Tip might be in order.