The Vocal QuickStrip

This tip is excerpted from the updated/revised 2nd Edition of How to Record and Mix Great Vocals in Studio One. The new edition includes the latest Studio One 5 features, as well as some free files and Open Air impulses, but also has 35% more content than the first edition—it’s grown from 121 to 194 pages. And as a “thank you” to those who bought the original version, you’re eligible for a 50% discount on the 2nd edition. There’s also a bundle with the book and my complete set of 128 custom impulses for Open Air…but so much for how I spent my summer vacation, LOL. Let’s get to the tip.

Suppose you’ve laid down your raw vocal—great! Now it’s time to overdub some instrumental parts and background vocals. Unfortunately, though, that raw vocal is kind of…uninspiring. So you start browsing effects, tweaking them, trying different settings—and before you know it, you’re going down a processing rabbit hole in the middle of your session.

Next time, open up the Vocal QuickStrip. Insert this vocal processing’s “greatest hits” FX Chain in your vocal track, tweak a few settings, admire how wonderful the vocal sounds, and then carry on with your project.

There’s a download link for the Vocal QuickStrip.multipreset file, so you don’t need to assemble the chain yourself. It works with Studio One 4 as well as 5 (note that the Widen button for the Doubler is functional only in Studio One 5).

The Effects

The Fat Channel (Fig. 1) is the heart of the chain. Of its three available compressors, the Tube Comp model emulates the iconic LA-2A compressor—the go-to vocal compressor for many engineers.

Figure 1: Fat Channel settings for the Vocal QuickStrip FX Chain.

The Fat Channel also includes a built-in high-pass filter. You can place the EQ either before or after the compressor; here, the EQ is before the compressor because boosting certain frequencies “pushes” the compressor harder. This contributes to the Vocal QuickStrip’s character.

The EQ uses all four stages. The most interesting aspect is how the Low Frequency and Low-Mid Frequency stages interact subtly when you edit the Bottom control. The Low-Frequency stage is fixed at 110 Hz with 1 dB of gain, but its Q tracks the Low-Mid Frequency stage’s Gain control. So, when you pull the LMF Gain down, the LF stage’s Q gets broader; increase Gain, and the Q goes up somewhat.

The High-Mid Frequency stage sits at 3 kHz, because boosting in this frequency range can improve intelligibility. The High-Frequency section adds “air” around 10 kHz. However, as you increase the Top control, the frequency goes just a bit lower so that the boost covers a wider section of the high-frequency range. This makes the effect more pronounced.

The Chorus is the next processor in the chain, but it’s used for doubling, not chorusing (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: The Chorus provides a voice-doubling ADT effect.

The parameters are preset to a useful doubling effect, and there are only two control switches—one to enable/bypass the effect, the other to increase the stereo spread.

For echo/delay effects, the Analog Delay comes next (Fig. 3). Although many of the parameters are well-suited to being macro controls, there had to be a few tradeoffs to leave enough space for the crucial controls from other effects.

Figure 3: The Analog Delay is set up for basic echo functionality.

For example, the Delay Time controls beats rather than being able to choose between beats and sweeping through a continuous range. Feel free to change the Macro control assignment. Also, the LFO isn’t used, so if you want to modify the ping-pong effects, you’ll need to open the interface and do so manually. In any event, the Delay Beats, Feedback, and Mix parameters cover what you need for most vocal echo effects.

The final link in the chain is the Open AIR reverb (Fig. 4). Normally I use my own impulse responses (see the Friday Tip Synthesize Open AIR Reverb Impulses in Studio One for info on how to create your own impulse responses), but of the factory impulses, for vocals I’m a big fan of the Gold Plate impulse. (If you have my Surreal Reverb Impulse Responses pack that’s available from the PreSonus shop, I’d recommend using the 1.2 Fast Damped, 1.5 Fast Damped, or 2.25 Fast Damped vocal reverbs. However, note that these three files are also included for free with the second edition of the Vocals book)

Figure 4: The Open AIR reverb plug-in’s Gold Plate impulse response is one of my favorite factory impulses for vocals.

The Macro Controls

When designing an FX Chain with so many available parameters, you need to choose which parameters (or combinations of parameters) are most important for Macro controls (Fig. 5).

Figure 5: The Vocal QuickStrip Macro controls.

Compress varies both the Peak Reduction and Gain to maintain a fairly constant output—an old trick (see the EZ Squeez One-Knob Compressor tip), but a useful one. Bottom, Push, and Top control three EQ stages. All of these, and the Compressor, have bypass switches so it’s easy to compare the dry and processed settings.

Delay also has a bypass switch, as well as controls for delay time in beats, delay feedback, and dry/wet delay mix. The only switches for the chorus-based doubling function are bypass and narrower/wider. Reverb includes a bypass button and dry/mix control, because that’s really all you need when you have a gorgeous convolution reverb in the chain.

So go ahead and download the Vocal QuickStrip, use it, and have fun. But remember that an FX Chain like this lends itself to modifications—for example, insert a Binaural Pan after the Open AIR reverb, or optimize some EQ frequencies to work better with your mic or voice. Try the other two compressors in the Fat Channel (or if you’re a PreSonus Sphere member, then try the other eight compressors—they all have different characters). With a little experimentation, you can transform an FX Chain that works for me (and will hopefully work well for you) to an FX Chain that’s perfect for you. Go for it!

Download the Vocal QuickStrip FX Chain here

Purchase How to Record and Mix Great Vocals in Studio One here

World-Renowned Drummer “Kirkee B” Talks PreSonus Sphere

If you know him well, you know him as “Kirkee B.” To the rest of us, Curt Bisquera is a world-renowned professional studio and live drummer. Having played with more famous artists than we have room to name in this blog post, he’s in-demand—both in the studio and on the road. Talk about a Dinner Party DREAM guest list: Mick Jagger, Elton John, Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers, Seal, John Fogerty, Sarah McLachlan, John Legend, Hans Zimmer, Josh Groban, Lana Del Rey, Celine Dion, Johnny Cash, Billy Joel, Tina Turner, Donny Osmond, Lionel Richie… those are a few of his credits over the last 30 years in the music industry.

We recently connected with Kirkee B on Instagram and found out he’s a HUGE PreSonus Sphere user and fan! We thought it would be nice to hear his thoughts on PreSonus Sphere.

How did you first hear about Sphere?

I heard about PreSonus Sphere through PreSonus’ Artist Relations Manager, Perry Tee. He really didn’t say what it was… he just said, “Look out for what’s coming… it’s gonna blow your mind!” And he was correct!

What got your attention?

The video content. I’m on Sphere every day watching all the new video content that’s posted. I’m getting better at using Studio One 5, thanks to all the videos from Gregor and Joe! They are a huge help and inspiration.

What’s keeping your attention?

The fact that it is always maintained and updated and that I can also join in with a bunch of other users around the world.

- Kirkee B with Sir Elton John

- Kirkee B in high school

- Kirkee B with Seal

- Kirkee B on Set of the Flintstones

Can you speak to the value of PreSonus Sphere?

Oh man, where to begin? After the morning espresso kicks in, there are two things I check: the news and PreSonus Sphere! I always feel like I’m on top by checking Sphere everyday… Super valuable!

Is there something specific that you’ve learned from one of the exclusive videos?

YES! I’ve learned how to use the Splitter Tool thanks for PreSonus Sphere and I LOVE IT!

What would you tell someone who’s considering Sphere?

Once you sign on, you will feel the world of creativity at your fingertips! There’s nothing like it.

In your opinion, how can PreSonus Sphere change the music industry?

It allows users to gain confidence at their own pace in using PreSonus products and software in an easy, one-stop, online environment. Confidence is huge if you want to be successful in this industry.

How does it feel to be one of the FIRST to join the PreSonus Sphere family?

I am honored! It’s really changed the game for me, now in my creativity is limitless. I can do things now I was unable to do in the past. NOW the future for me is PreSonus Sphere!

Join PreSonus Sphere today!

Connect with Curt on Instagram here!

Sweet Multiband Chorus

Full disclosure: I’m not a big fan of chorusing. In general, I think it’s best relegated to wherever snares with gated reverbs, orchestral hits, DX7 bass presets, Fairlight pan pipes, and other 80s artifacts go to reminisce about the good old days.

Full disclosure: I’m not a big fan of chorusing. In general, I think it’s best relegated to wherever snares with gated reverbs, orchestral hits, DX7 bass presets, Fairlight pan pipes, and other 80s artifacts go to reminisce about the good old days.

But sometimes it’s great to be wrong, and multiband chorusing has changed my mind. This FX Chain (which works in Studio One Version 4 as well as Version 5) takes advantage of the Splitter, three Chorus plug-ins, Binaural panning, and a bit of limiting to produce a chorus effect that covers the range from subtle and shimmering, to rich and creamy.

There’s a downloadable .multipreset file, so feel free to download it, click on this window’s close button, bring the FX Chain into Studio One, and start playing. (Just remember to set the channel mode for guitar tracks to stereo, even with a mono guitar track.) However, it’s best to read the following on what the controls do, so you can take full advantage of the Multiband Chorus’s talents.

Anatomy of a Multiband Chorus

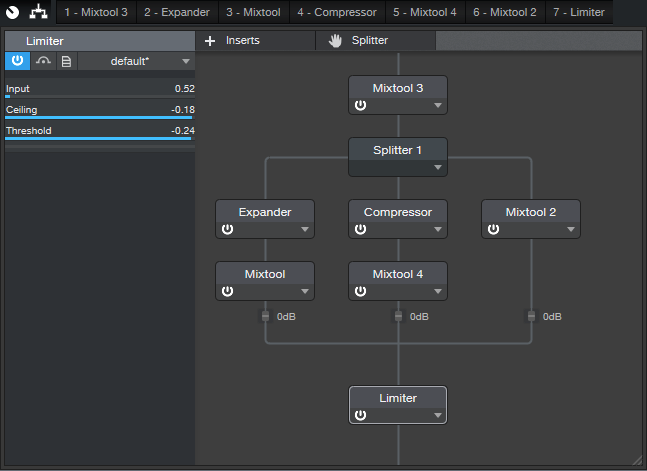

The Splitter creates three splits based on frequency, which in this case, are optimized for guitar with humbucking pickups. These frequencies work fine with other instruments, but tweak as needed. The first band covers up to 700 Hz, the second from 700 Hz to 1.36 kHz, and the third band, from 1.36 kHz on up (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. FX Chain block diagram and Macro Controls panel for the Multiband Chorus.

Each split goes to a Chorus. The mixed output from the three splits goes to a Binaural Pan to enhance the stereo imaging, and a Limiter to make the signal “pop” a little more.

Regarding the control panel, the Delay, Depth, LFO Width, and 1/2 Voices controls affect all three Choruses. Each Chorus also has its own on/off switch (C1, C2, and C3), Chorus/Double button (turning on the button enables the Double mode), and LFO Speed control. You’ll also find on/off buttons for the Binaural Pan and Limiter, as well as a Width control for the Binaural Pan. Fig. 2 shows the initial Chorus settings when you call up the FX Chain.

Figure 2. Initial FX Chain Chorus settings.

The Multiband Advantage

Because chorusing occurs in different frequency bands, the sound is more even and has a lusher sound than conventional chorusing. Furthermore, setting asynchronous LFO Speeds for the three bands can give a more randomized effect (at least until there’s an option for smoothed, randomized waveform shapes in Studio One).

A major multiband advantage comes into play when you set one of the bands to Doubler mode instead of Chorus. You may need to readjust the Delay and Width controls, but using Doubler mode in the mid- or high-frequency band, and chorusing for the other bands, gives a unique sound you won’t find anywhere else. Give it a try, and you’ll hear why it’s worth resurrecting the chorus effect—but with a multiband twist.

Download the .multipreset here.

The Limiter2 Deep Dive

At first, the changes to the effects in Version 5 seem mostly cosmetic. But dig deeper, and you’ll find there’s more to the story—so let’s find out what’s new with Limiter2 (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Limiter2 has had several design changes for Version 5.

The control parameters are more logical, and easier to adjust. Prior to V5, there was an unusual, by-design interaction with the Ceiling and Threshold controls; setting Ceiling below Threshold gave the limiter a softer knee. However, the tradeoff was difficulty in obtaining predictable results. Besides, if the soft knee aspect is important to you for dynamics control, just use the Compressor with a really high ratio.

In Limiter2, the Threshold is relative to the Ceiling—the Ceiling sets Limiter2’s absolute maximum level, while Threshold sets where limiting begins below the Ceiling, based on the Threshold parameter value. For example, if Ceiling is 0.00 and Threshold is -6.00, then the limiter’s threshold is ‑6.00 dB. But if the Ceiling is ‑3.00 dB and the Threshold is -6.00, then the limiter’s Threshold is -9.00 dB. Makeup gain occurs automatically so that as you lower the Threshold parameter, the output level increases as needed to meet the Ceiling’s target output level.

Modes and Attacks

There are now two Modes, A and B, and three Attack time settings. The pre-V5 Limiter had less flexible attack options, which mostly impacted how it responded to low-frequency audio; the waveform could have some visible distortion when first clamped, but the distortion would disappear after the attack time completed.

I’ll spare you the hours I spent listening and nerding around with the (highly underrated) Tone Generator and Scope plug-ins to analyze how the new options affect the sound, so here’s the bottom line.

In applications where you want to apply something like 6 dB of peak reduction to make a track or mix “pop,” the Limiter2 performance in Mode A is essentially perfect. Unless you’re into extreme amounts of limiting or material with lots of low frequencies, Mode A should cover what you need 95% of the time (and it also outperforms the pre-V5 limiter).

If you’re using Limiter2 as a brickwall limiter to keep transients from spilling over into subsequent stages, then use Mode A/Fast attack for the highest fidelity and give up a tiny bit of headroom, or Mode B/Fast Attack for absolute clamping.

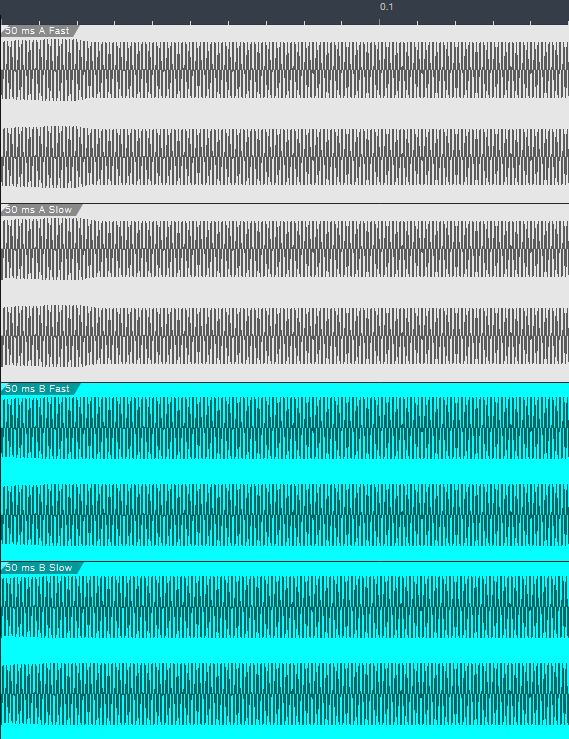

Fig. 2 shows how the fast and slow times compare. The following were all set for 50 ms release times, 1 kHz sine wave input, and -20 dB Threshold—so Limiter2 was being hit pretty hard.

Figure 2: Fast and Slow attacks compared for Modes A and B, cropped to 150 ms duration. Top to bottom: Mode A/Fast, Mode A/Slow, Mode B/Fast, Mode B/Slow.

The visuals are helpful, but on signals with fast transients, you may hear more of a difference with the different attack times than these images might indicate. Nonetheless, it’s clear that Mode B/Fast is super-fast. If you look carefully at Mode A/Slow, you’ll see a very tiny downward blip on the first cycle of the attack (it’s less visible on Mode B/Slow). Mode A takes about 20 ms to settle down to its final level.

Low-Frequency Performance

For more background on the nuts and bolts of how this works, the tradeoff for Mode B’s higher speed mostly involves very low frequencies (under 80 Hz or so, and especially under 50 Hz). With a 50 Hz sawtooth wave, 100 ms Release, and a significant amount of limiting, Mode B/Slow gives some visible overshoot and distortion. Mode B/Fast reduces the overshoot but increases distortion. Mode A does less of both—with Slow, there’s less overshoot, and with Fast, there’s less distortion. Note that any distortion or overshoot occurs only when pushing Limiter2 to extremes: very low-frequency waveforms, with steep rise/fall times, short release times, and lots of limiting. However, this is mostly of academic interest with waveforms that have lots of harmonics, like sawtooth and square. The level of the harmonics is high enough to mask any low-level harmonics generated by distortion.

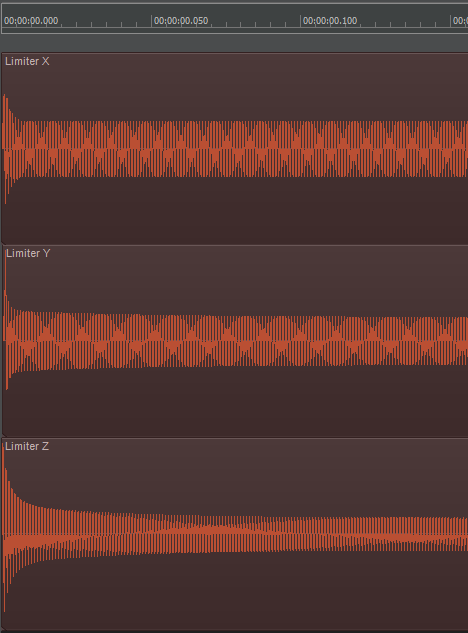

I also tested with a sine wave, which gives an indication of what to expect with audio like a kick drum (e.g., 40-60 Hz fundamental) or low bass notes. Mode B/Fast has less distortion than Mode B/Slow, while Mode A, fast or slow, flattens peaks almost indiscernibly (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: A 30 Hz sine wave with about 15 dB of limiting. Top: A Mode. Middle: B Mode/Fast. Bottom: B Mode/Slow.

In this situation, Mode A would likely be my choice, but as always, use your ears—the light distortion from Mode B can actually enhance kick drum and bass tracks. Also note that which mode to use depends on the release time. For example, with a short (35 ms) release, B/Slow had the most audible distortion, B/Fast was next, and B/Normal had no audible distortion.

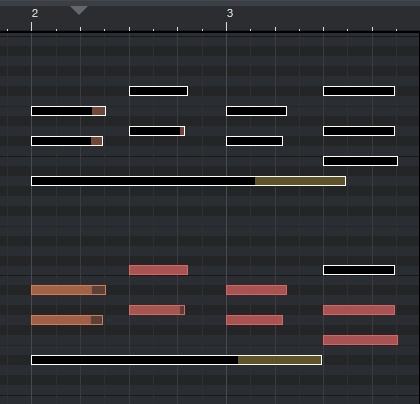

While I was in testing mode, I decided to check out some third-party limiters (Fig. 4) with a different program. These are all marketed as “vintage” emulations, and set to the fastest possible attack time.

Figure 4: The results of testing some other limiters.

In case you wondered why some people say these vintage limiters have “punch”…now you know why! The time required to settle down to the final level is pretty short (except for the bottom one), but the limiter doesn’t catch the initial peaks. This is why you can insert one of these kinds of limiters, think you’re limiting the signal, but the downstream overload indicators still light on transients. Incidentally, the Fat Channel’s Tube limiter has this kind of “vintage punch” response in the Limit mode, while the Fat Channel’s one-knob, final limiter stage—although basic—is highly effective at trapping transients.

Why Overlap Correction is Totally Cool

Studio One’s Overlap Correction feature for Note data isn’t new, but it can save you hours of boring work. The basic principle is that if Note data overlaps so that the end of one note extends long enough to overlap the beginning of the next note, selecting them both, and then applying overlap correction, moves the overlapping note’s end earlier so that it no longer overlaps with the next note.

My main use is with keyboard bass. Although I play electric bass, I often prefer keyboard bass because of the sonic consistency, and being able to choose from various sampled basses as well as synth bass sounds. However, it’s important to avoid overlapping notes with keyboard bass for two main reasons:

- Two non-consonant bass notes playing at the same time muddies the low end, because the beat frequencies associated with such low frequencies are slow and disruptive.

- The sound is more realistic. Most bass parts are single-note lines, and with electric bass, there’s usually a finite amount of time between notes due to fingering the fret, and then plucking the string.

One option for fixing this is to zoom in on a bass part’s note data, check every note to make sure there aren’t overlaps, and shorten notes as needed. However, Overlap Correction is much easier. Simply:

- Select All Note data in the Edit View.

- Choose Action > Length, and then click the Overlap Correction radio button.

- Set overlap to -00.00.01.

- Click OK.

Normally I’m reluctant to Select All and do an editing function, but any notes that don’t overlap are left alone, and I haven’t yet run into any problems with single-note lines. Fig. 1 shows a before-and-after of the note data.

Figure 1: The notes circled in white have overlaps; the lower copy of the notes fixes the overlaps with the Length menu’s Overlap Correction feature.

Problem solved! The reason for setting overlap to -00.00.01 instead of 00.00.00 is because with older hardware synthesizers or congested data streams, that very slight pause ensures a note-off before the next note-on appears. This prevents the previous note from “hanging” (i.e., never turning off). You can specify a larger number for a longer pause—or live dangerously, and specify no pause by entering 0.

Also, although I referenced using this with keyboard bass, it’s useful for any single-note lines such as brass, woodwind, single-note MIDI guitar solos, etc. It can also help with hardware instruments, including electronic drums, that have a limited number of voices. By removing overlaps, it’s less likely that the instrument will run out polyphony.

There’s some intelligence built into the overlap correction function. If a note extends past another note, there won’t be any correction. It also seems to be able to recognize pedal points (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Overlap Correction is careful about applying correction with polyphonic lines.

Selecting all notes in the top group of notes and selecting Overlap Correction didn’t make any changes. As shown in the bottom group of notes, preventing the pedal point from overlapping the final chord requires selecting the pedal point, and any of the notes in the last chord with which the pedal point overlaps.

It’s easy to overlook this gem of a feature, but it can really help with instrumental parts—particularly with keyboard bass and solo brass parts.

Sound on Sound Reviews Studio One!

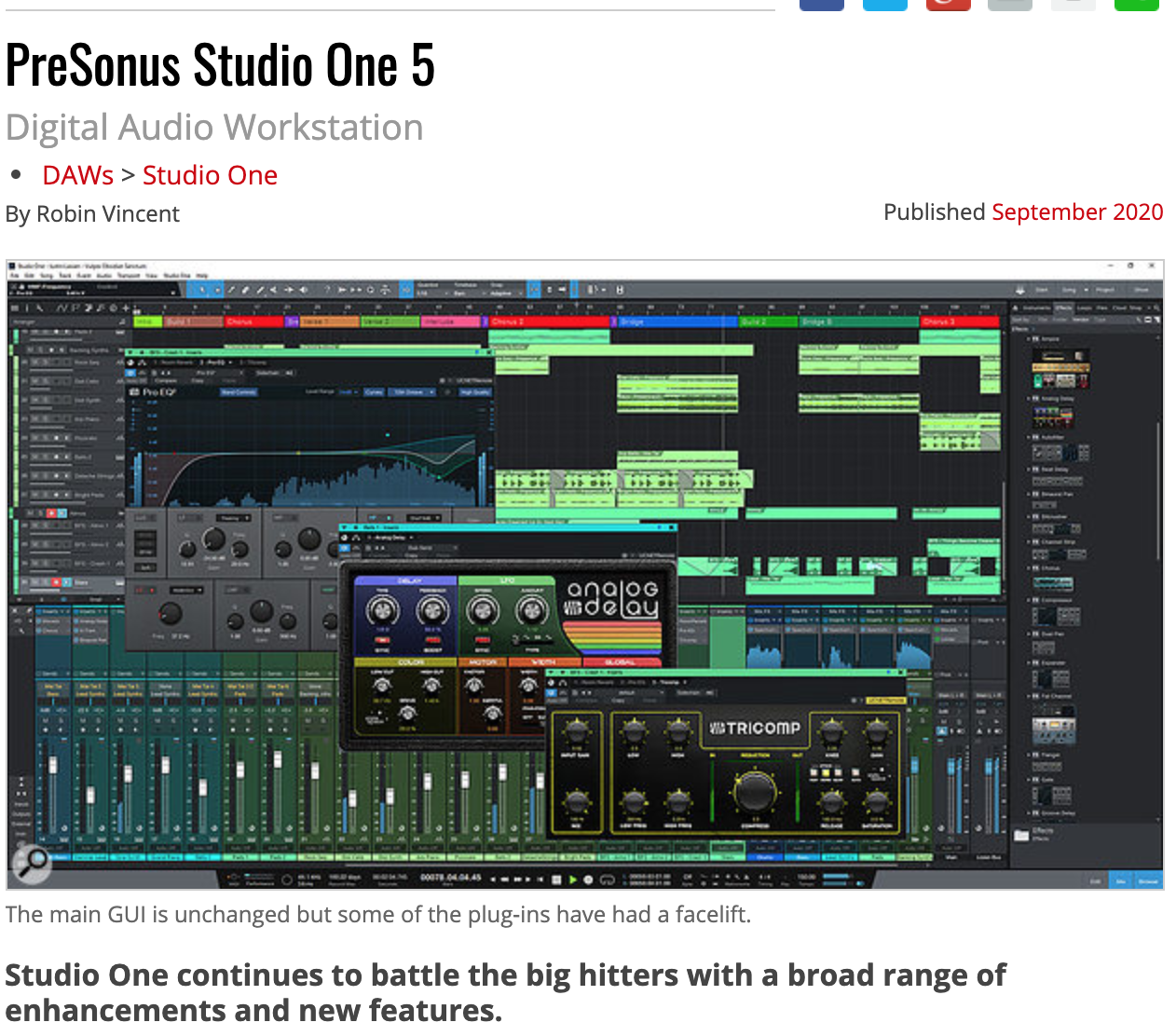

Sound on Sound Magazine is “the independent voice of music recording technology for over 34 years.” Their team is based in the United Kingdom and, like the rest of the world, Covid-19 has thrown a wrench in their day-to-day and service to their customers. In response to the lockdown, they’re now offering access to their September issue for FREE! Read cover to cover digitally here.

The PreSonus Quantum landed on the cover of Sound on Sound back in 2017. We are very excited to see Studio One featured in their latest issue! Writer Robin Vincent gives an extremely detailed review of many of Studio One 5’s enhancements, new features and so much more. All we can say is THANK YOU!

Here is a direct link to their deep dive into Studio One 5!

They also shout out to PreSonus Sphere! Here’s a little snippet:

The pricing is impressive, achievable, realistic and it keeps you in the upgrade loop.

Learn more about PreSonus Sphere here: https://shop.presonus.com/PreSonus-Sphere

Transient Shaper FX Chain

As you can probably tell, I’m a fan of FX Chains—they satisfy my inner DIY impulse to put things together, and result in some cool, useful, new processor I didn’t have before. For this Friday’s tip, let’s put together a Transient Shaper designed specifically for drums and percussion. It can emphasize the attack, the post-attack section (called “Girth” in the FX Chain), or both, as well as mix any blend of them. Of course, there’s a download link for the multipreset—but first, let’s listen to what transient shaping can do.

The first two measures are the straight Crowish Acoustic Bridge 2 w. Fill drum loop from Studio One’s sound library. The next two measures add Attack shaping, the next two add Girth only, and the final two measures combine Attack and Girth, with 1 dB of limiting. All examples are normalized to the same peak level.

How it Works

Fig. 1 shows the block diagram. Mixtool 3 adjusts the input level, because when feeding any dynamics processors, you need to find the sweet spot where the processors act as expected. In this case, you want the input level to provide a signal that uses up most of the headroom.

The incoming audio splits into three paths. The left path is an expander, set up to provide upward expansion. This is what emphasizes the attack. The Mixtool adjusts the path’s level.

The middle path is a compressor, set for the shortest attack time possible to reduce any existing attack to a minimum. Some compression brings up the post-attack part of the audio. Mixtool 4 adjusts this path’s level.

The right-most path sets the dry signal’s level. This is an important parameter, because you can take out the dry signal and be left with only what’s contributed by the Attack and Girth paths, or use them to enhance the dry sound.

The Macro Controls

It takes a little effort to get familiar with the controls. The Attack shaper is the main point of this FX Chain, so to acquaint yourself with what the Attack parameters do, load up a drum loop of your choice, and then do the following.

- Turn Girth, Dry, and Limiting down all the way.

- Turn off all switches except Attack Enable.

- If the drum loop doesn’t use up the available headroom, normalize it, or turn up the input control.

- Turn the three attack-related controls up about 2/3 of the way. Vary Attack Width; turning it clockwise shortens the attack transient.

- Set Attack Width to around 1:4.5. Now, vary the Attack Amount. Turning it counter-clockwise raises the level below the attack. This provides a smoother transition if the enhanced attacks sound too isolated.

- Turn up the Dry control about 2/3 of the way. Mix in the desired amount of attack with the Attack Level control.

- Next, disable Attack, enable Girth, and vary the Girth control to find out how it affects the sound. As with Attack, you can vary the proportion of the Girth and Dry sounds.

- The Inv Phase button inverts the Dry path phase. It’s not something you’d normally enable, unless you’re in search of bizarre special effects…but you’re a creative bunch, so I figured I might as well put it in.

- If you want to perk up those drums even further, go ahead and slam the limiter.

One final comment: It’s easy to go overboard with transient shaping, but after the novelty wears off, you’ll find that even a little bit of enhanced attack can make a track sound more lively. And while we’ve covered this only with drums, it also works for bass attacks, plucked strings, and strange percussion instruments…basically if something has an attack, this FX Chain can shape it.

Download the preset here!

Studio One 5’s Dynamic EQ Meets EDM

I’ve always loved having one track impart its characteristics to a different track (“cross-modulation”), particularly for EDM. A good example is using a vocoder for “drumcoding,” where drums—not a microphone—provide the vocoder’s modulation source. Previous Friday Tips along these lines include The Ultra-Tight Rhythm Section, Smoother/Gentler Sidechain Gating, Pumping Drums – With No Sidechain, and most recently, Rockin’ Rhythms with Multiband Gating.

Sending audio from one track over a sidechain to control dynamic EQ in another track is great for cross-modulation effects—and now this is easy to do in Studio One 5 because sidechaining has been added to the Multiband Dynamics processor. One of my favorite effects is using the kick drum to boost the upper midrange on a rhythm guitar part or keyboard pad so that the guitar or pad emphasizes the rhythm…and that’s just one possibility.

This isn’t about “textbook” dynamic EQ in the sense of being able to use any type of filter (e.g., highly resonant bandpass) as the EQ, but as pointed out in the Friday Tip Studio One’s Secret Equalizer, the Multiband Dynamics combines both EQ and dynamics. We’ll use that to our advantage—and in a way, a relatively broad filter response is better for this kind of application. (The typical dynamic EQ application involves fixing a problem, and for that, you often need precise filtering.)

The Setup

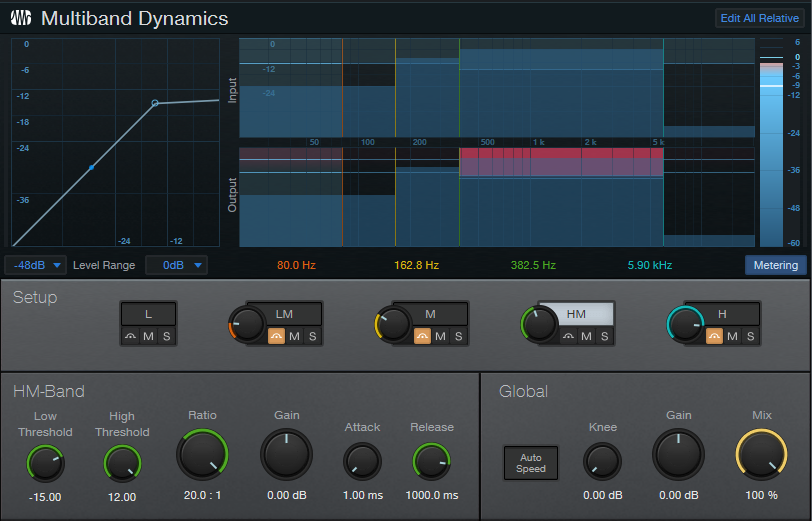

Insert the Multiband Dynamics in the Target track, like guitar, pad, organ, etc. Then, insert a Send (pre-fader is probably best) in the Source track (e.g., kick or snare drum). Assign the Send to the Multiband Dynamics sidechain (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: This technique requires a source track to trigger the Multiband Dynamics’ sidechain and a target track that’s processed by the Multiband Dynamics.

Multiband Dynamics Settings

This is where the fun begins. The sidechain feeds all Multiband Dynamics bands simultaneously, so the most basic implementation would be bypassing all the bands except for one, which you then set to either cut or boost a particular frequency range. The amount of boost or cut depends on the level that the source track sends to the sidechain.

For example, with compression, you can create pumping effects (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: The Multiband Dynamics attenuates the selected frequency range whenever it receives a signal from the source track.

In this example, a kick drum is modulating a pad. Every kick drum hit attenuates the HM (High-Mid) range; the amount of attenuation fades over the 1000 ms Release time. A shorter Release parameter creates a more percussive effect. Choose the frequency range you want to modulate by adjusting the crossover frequencies. Even better, note that you can automate the Multiband Dynamics’ crossover frequencies, so the frequency range can sweep over time—this is a novel effect that adds considerable animation.

Another option is to raise the target band’s Gain so that any modulation lowers the band’s level. In other words, the default state for that band is boosted, and modulation reduces the boost.

You can also boost a band’s level in response to dynamics, by setting the Multiband Dynamics parameters for upward expansion (Fig. 3). Note how the graphic in the upper left shows an expansion curve instead of one for compression.

Figure 3: Upward expansion boosts the target audio in the selected frequency range.

The control settings here are fairly crucial. Ratio must be set for upward expansion, so the second number in the ratio control needs to be greater than one—the bigger the number, the steeper the expansion. For the maximum expansion effect, set High Threshold to 12.00. The Low Threshold parameter determines where expansion begins, and Gain increases the overall level to compensate for the lower level below the point where expansion kicks in. Adjust Attack and Release to shape the boost’s dynamics. Because upward expansion boosts the output signal level, you may need to reduce the Global gain somewhat.

But Wait—There’s More!

The best way to understand all the possibilities is to create a basic setup like the one in Fig. 1 with a kick drum as the source and a very simple, sustained pad (e.g., a chord with sawtooth waves) as the target. This will make it easy to hear the results of playing around with the Multiband Dynamics’ controls. And of course, it is a multiband processor, and the sidechain feeds all the bands, so you could have one band attenuating while another is boosting. If you get into automating parameters, the sky’s the limit.

Dynamic EQ can also be useful to process signal processing. For example, suppose there’s a main reverb inserted in a bus, to which you send drums, guitar, voice, etc. To avoid muddiness, insert a Multiband Dynamics after the reverb, use kick as the sidechain source, and attenuate the low frequencies whenever the kick hits.

Cross-modulation with dynamic EQ can be serious fun…give it a try.

Bucket Brigade Delay FX Chain

I wanted a Bucket Brigade Delay (BBD) effect in Studio One. Seriously.

Although some analog delays (e.g., Binson Echorec) were based on tape, others used analog “bucket brigade” technology. Bucket brigade integrated circuits (like the Panasonic/Matsushita MN3005 or Reticon SAD-1024) incorporated thousands of capacitive elements controlled by a clock. Each clock cycle passed the analog signal at the input from one stage to the next, so slower clocks meant longer delays. But because sampling (albeit analog) was involved, so was the Nyquist theorem—the more you slowed down the clock, the more likely you’d hear aliasing and distortion. At really long delays, sometimes you’d even hear leakage from a clock that had gotten down to the audible range.

So I emailed Arnd Kaiser, the General Manager for PreSonus Software, and told him I wanted to modify the Analog Delay into a BBD. He seemed puzzled and said that if you turn up the Drive and lower the High Cut frequency at longer delays, you’ll get the BBD sound. True, but that sound is of a clean, well-designed BBD where the designer didn’t push the chips, and knew how to layout a circuit board. That’s fine, but I wanted filth…time for an FX Chain (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: The Analog Delay plug-in is the heart of this FX Chain.

The solution was tracking the Delay Time with the BitCrusher’s Downsampling parameter, so at longer delay times, those lovely violations of Mr. Nyquist’s theorem could grace the sound with aliasing and sonic nastiness.

I was running late submitting the tip because of going down this crazy BBD rabbit hole, so I emailed Ryan Roullard at PreSonus (who among a zillion other things makes sure my Friday Tips roll along smoothly every week) to apologize for the delay and give him a heads-up of what to expect for this week’s tip. He asked if I’d included the clock leakage whine as part of the sound. I was embarrassed to say that I had overlooked it, but Ryan said that if I figured out how to add it in, he’d never tell anyone of my shameful omission.

You can download the Bucket Bridge Delay.multipreset, so I won’t go into much detail—reverse-engineer it to find out how it works, or modify it to do even stranger things. Please note: It’s probably best to insert this into an FX Bus with the Mix control set to wet only because unless none of the three switches is enabled, there’s no way to have a completely clean sound.

The important part is the three switches—Arnd, Craig, and Ryan. You can select none of them or any/all of them. With none of the three switches selected, you have a standard Analog Delay sound, with the other knobs and buttons doing their standard Analog Delay functions. But…

- Click Arnd, and now increasing the delay Time increases the State Space drive, and pulls back on the High Cut, to get that BBD-but-still-fairly-clean sound.

- Click Craig, and now the Bitcrusher Downsampling tracks the Delay Time as well.

- Click Ryan, and you’ll introduce that lovely clock whine, whose frequency also tracks the Delay Time. The whine has its own dedicated level control so you can decide how much clock leakage you want in the sound. (Pro Tip—turn it up to emulate the sound of a bad circuit board layout!)

And there you have it—delicious, modern digital meets filthy, vintage analog. Have fun!

Download the Bucket Bridge Delay.multipreset Here!

Notion iOS 2.5.3 Release Notes

Notion iOS 2.5.3 Maintenance Release

![]() An update is now available to the recent 2.5 release for Notion iOS, the best-selling notation app on iOS. This is a free update for Notion iOS owners that can be obtained by visiting Notion in the App Store on your device, or checking your available updates in the App Store.

An update is now available to the recent 2.5 release for Notion iOS, the best-selling notation app on iOS. This is a free update for Notion iOS owners that can be obtained by visiting Notion in the App Store on your device, or checking your available updates in the App Store.

All the changes are below—if you missed all the major news for v2.5 itself, check it out here.

And while you’re here, please join us at our new official Facebook user group: https://www.facebook.com/groups/PreSonusNotionUsers

All Fixes and Enhancements:

Restore Purchases:

- New ‘Restore Purchase’ button in Settings>Handwriting

- ‘Restore Purchases’ in Sounds menu no longer also triggers downloading the sounds – it just restores the purchase state

Dragging Improvements:

- Fix for flickering when dragging score items

- Score items can now be more easily dragged across measure lines and between staves

- Improvement when dragging and dropping score item between staves

- Final drag position of score items more accurate

- Stability when dragging improved

General:

- Stability and performance improvements

- Fix for ‘Insert Barlines’ dialog position on iPhone

- General translation fixes

- Now uses original language expression text in Chinese localization (e.g. arco, pizz)

- Key signature is now always sent in MIDI export even if it is C major

- Minimum requirements: Apple iOS9 or higher (please note, Notion 2.5.x will be the final version to support iOS9 and iOS10)