Category Archives: Friday Tip of the Week

Studio One’s VCA Module

A modular synthesizer’s VCA (Voltage-Controlled Amplifier) changes gain in response to an input control voltage. One of my favorite applications is controlling a VCA with an envelope follower—for example, using an envelope follower on drums, and running power chords, pads, or sustained synth sounds through the VCA. Then, these sounds take on the percussive characteristics of the drum part. But Studio One doesn’t have a VCA, right?

Actually, it does—the Expander. You can set up the Expander to act like a VCA, with its gain controlled by a sidechain signal. So, in the example above, you can run sounds like guitar chords through the Expander, and feed the Expander’s sidechain from a drum track. Here’s what it sounds like.

[Caption] The first four measures, drums modulate the guitar. The second four measures use the Analog Delay to provide an additional 1/8th-note rhythm.

Test Setup

Fig. 1 shows a test setup to play around with this process, and hear how it works. Insert a drum loop in one track. Normalize it so the signal level is consistent. The drums provide the sidechain signal.

In another track, insert the Tone Generator set for pink noise, followed by the Expander. Using pink noise makes it easy to hear how adjusting Expander parameters alters the pseudo-VCA’s response to drums.

Start with the Expander settings shown in fig. 1, and assign a pre-fader send from the drum track to the Expander’s sidechain. Note that when you assign a sidechain to the Expander, it automatically selects Ducking mode. You don’t want this, so de-select Ducking.

Start playing the drum loop, and you should hear the white noise’s amplitude being modulated by the drums. If not, make sure the drum track send provides enough level to the expander sidechain. Here’s how the Expander controls affect the sound.

- Release: Start by varying the Release. Longer times add a decay to the pink noise.

- Attack: This isn’t as useful with percussive sounds, because the sound is over before the attack can complete. But if the sidechain signal is coming from something like a pad, you’ll hear an attack time superimposed on the noise.

- Range: This acts like a bias voltage for the VCA, that always keeps it somewhat open. It’s good for when you want the VCA to be affected only by the drum peaks.

- Threshold: Lower this to pick up more of the peaks. It’s kind of like compressing the sidechain signal.

- Ratio: Higher ratios make the effect more percussive, to the point where the sound is so percussive you might not hear the drums anymore. Lower ratios create a less percussive sound, somewhat like changing the ratio.

Now that you know what this technique can do, start running other signals through the Expander. And by the way—automating Threshold and Release can add some serious animation to the percussive effects. Check it out!

Parallel? Narrow? Bass? Say What?!?

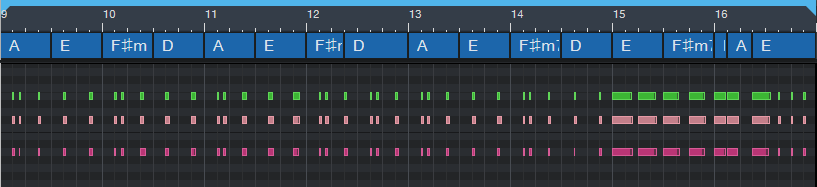

It’s probably obvious that I love the Chords track. It’s so useful that if you haven’t made friends with it yet, look over the Reference Manual…then take it out for lunch. Meanwhile, here’s a way to have it create a rhythmic keyboard part—with very little effort.

One of the Chords track’s (many) talents is generating a chord chart from your playing. Play an acoustic instrument like guitar (yes, chords are allowed) or a MIDI instrument like Presence, then drag the audio or MIDI data up to the Chords track. It automagically maps out your chord progression.

Tip: Quantize the part before you drag it up, so that chord changes happen on the beat where they’re supposed to change. Or quantize the Chords track after it’s extracted, so that the chord changes line up on the beat.

Once the Chords track extracts the progression, any subsequent audio or MIDI parts you record can follow the chord progression. Audio has more options than MIDI, so for this blog post, we’ll just consider the MIDI aspect.

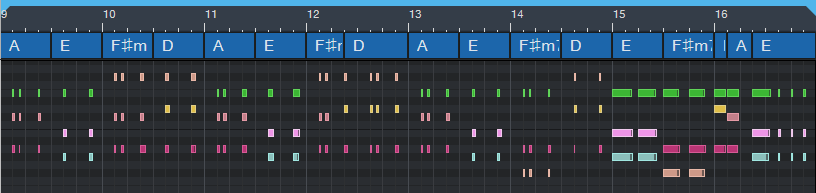

The keyboard overdub shown in fig. 1 is not following the chord track that was extracted from guitar. Actually, all it’s doing is playing the same chord with different rhythms. But we’ll fix this.

It sounds as useless as it looks—and to prove it, check out the following audio example. I’ve left the guitar, bass, and drums in for context. The keyboard part is panned right, and mixed up fairly high so you can hear the part easily.

Tip #2: When using the Chords track as a songwriting partner, don’t be too concerned about the notes you play—the Chords track will fix them. Just nail the timing, and play in the general vicinity of the note range you want the final part to cover.

To have the MIDI notes follow the Chords track, click on the track, open the Inspector (F4), and from the Follow Chords drop-down menu, choose Narrow. This moves the notes to the nearest note that conforms to the chord specified in the Chords track (fig. 2). Looks a lot better, doesn’t it?

And it sounds a lot better, too, as you’ll hear in the next audio example.

The Parallel option shifts the notes in parallel, so that a chord’s root notes line up with the root note of the chord in the Chords track. This typically creates voicings that cover a wider pitch range, which may or may not be what you want. However, occasionally this will transpose some notes so they’re not in the right key. If so, you’ll need to do a little manual editing. Here’s what Parallel mode created (fig. 3).

And here’s what it sounds like.

Following the chord track in Bass mode isn’t relevant here, because it just aligns the chord’s lower note with the Chords track chord—the end result is the same as choosing Parallel, which definitely doesn’t generate a fun bass line. But as described previously in the blog post Studio One’s Session Bass Player, combining the Chords track with the Fill Notes option can create some pretty amazing bass parts.

Oh, and if someone wants to spoil the fun and say you’re “cheating,” remind them the only thing that matters about music is the emotional impact on the listeners—and if they like what they hear, they won’t care what you did to get there.

Lively Up Your Drums

One element that can help make drums exciting is including the room sound where the drums were recorded. If you don’t believe me, listen to the drum part in Led Zeppelin’s “When the Levee Breaks.”

I rest my case.

When mixing drums, if there wasn’t a separate track of miked room sound, or you’re using a pre-recorded loop, you do have options. You can add a room sound with reverb, but that won’t be the same as the room where you recorded the drums. Or, you can compress the drums, which will bring up the room sound—but also squash the peaks.

The best option would be bringing up the room sound without squashing the peaks. Fortunately, with parallel compression, you can do this. The trick is to set a super-low threshold, then add some compression. This brings down the peaks, but keeps the low-level audio intact. Turning up the Mix control just a bit brings in the low-level sounds, but because most of the mix contains the dry drums, you won’t squash any of its peaks. Now you have full peaks and room sound—as you’ll hear in the audio example. The first half is the drums by themselves. The second half enhances the room sound using this technique.

How It Works

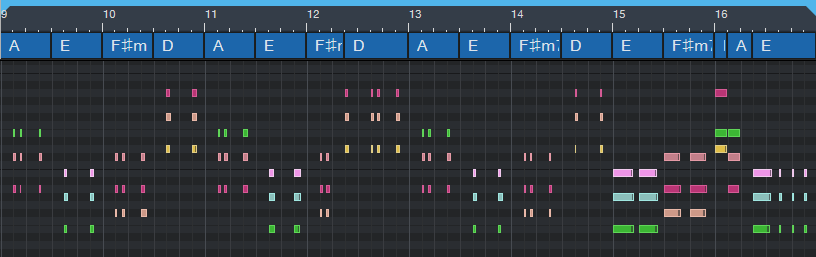

Insert the Compressor in your drum track, and set the compressor parameters as shown in fig. 1 (or just download the preset). Here’s what the controls do.

-48.00 is the lowest possible threshold. A 2.0:1 ratio adds enough compression to bring down the peaks so they don’t interfere with the dry signal, without sounding too compressed.

A tight compression sound is important for drums, so set the attack to minimum and about 50 ms of release. Don’t click Auto, because we’re not using the compressor in a standard way.

The Low Cut filter reduces the kick’s effect on the compression, so the lower-level sounds aren’t “pumped” by the kick. You’ll probably need to add some makeup gain; the preset uses 8.00 dB. The Mix control dials in the desired amount of room sound. With the settings shown, and a drum track that’s normalized to maximum, 30% seems about right.

And that’s all you need to do to lively up your drums. If you still want to squash the peaks too, then insert a Limiter2 after the compressor. But also note that this technique can bring up the body sound of acoustic guitars, bowing sounds with string sections, mouth sounds with vocals, and the like. Experiment!

Create Your Perfect Vocal Channel Strip Preset

First, some news: If you own The Huge Book of Studio One Tips and Tricks, the free update to version 1.2 is available from the PreSonus shop. Just go to your account and re-download the book. Also, my 2021 album project was recorded entirely in Studio One, and the playlist is posted on YouTube. You’ll probably find the song “I Hope” of particular interest, because the keyboard part was created automatically (yes, it really was) using the tip about the “Fill Notes” function, and the guitar and keyboard parts use the Shimmer Reverb tip. Okay, on to this week’s tip…

We all know how important vocals are, and the Fat Channel is an excellent channel strip for creating vocal presets. So, let’s go step-by-step on how to create your own Fat Channel preset. We’ll cover the reasons for choosing the parameters in fig. 1, and the order in which you want to edit them. More importantly, we’ll describe how to customize parameters for your mic type and voice.

HPF/Gate

The HPF can reduce pops, as well as excessive bass from singing too close to the mic. Choose a frequency that tightens up the low end, but doesn’t thin the sound. With a ribbon mic, you might want a higher frequency.

To keep low-level noise out of a vocal, try setting the Expander threshold to -55 dB. This should be high enough to get rid of residual hiss and room noise, but low enough to retain vocal nuances.

Equalizer

EQ settings are like a combination lock—get them right, and your vocal opens up. As to signal chain placement, equalizer before compressor is more forgiving of substantial EQ boosts that create “character.” Let’s run through the order for adjusting the edits.

HS (High Shelf). This gives the vocal “air.” Freq will be in the 8 to 10 kHz range, but Gain depends on your mic. Some mics have a high-frequency lift, so you don’t need much gain. A ribbon mic might sound dull, and need more gain. Turn up the Gain to where you get sibilance problems, and then back off until the sibilance issues go away.

HMF. The frequency range from 2 to 5 kHz is all about intelligibility. A broad boost helps the vocal stand out in a mix. Turn up the Gain until you hear more definition and greater intelligibility, then back off just a bit. The ear is most sensitive in this range, so too much boost can sound harsh.

LMF. A broad cut in the lower mids between 200 and 500 Hz can reduce “muddiness.” This isn’t always necessary, but reducing the lower mid response leaves more room for other instruments. Besides, with the HMF and High Shelf boosts, the vocal should come through just fine. An easy way to adjust LMF is to temporarily increase the Gain in this range, and sweep the frequency for the most “boxy” sound. That’s where you want to cut.

LF. With the HPF active and LMF cutting, a slight boost here re-introduces a little more warmth into the vocal. With a ribbon mic, or if the vocal was recorded with a significant bass proximity effect from singing too close, you might want to cut here instead.

Compressor

The Tube Comp is a favorite for vocals, and it’s blissfully easy to adjust: Set Peak Reduction for the desired amount of compression, then use Gain to make up for any decrease in level caused by compression. I usually aim for 6 to 8 dB compression on peaks, but a lot of engineers like to slam the compression harder, especially for rock vocals.

Limiter

Setting this to -3.0 provides insurance against stray peaks going higher than desired.

The Preset

The downloadable preset has the parameters shown in fig. 1. Although it can serve as a point of departure, I strongly encourage you to tweak the parameters to perfection for your own voice and microphone. You’ll find the effort is worth it!

Download the Fat Channel preset here:

Slick Tricks for Stack and Strum

Version 5.5 introduced Chord Stack and Strum features, which are pretty cool (for the basics on how they work, check out Gregor Beyerle’s YouTube video). We’ll warp these functions in some novel ways.

Chord Stack Meets Arpeggio

You can combine creating a Chord Stack and arpeggiating it at the same time.

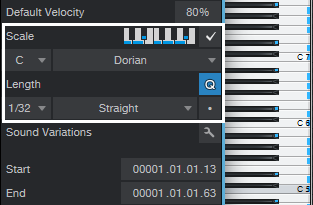

- Start by selecting the desired Key, Scale mode, note length, and clicking the Scale check box (fig. 1). I find the most reliable option is to click Q, which follows the current quantization setting (quantization doesn’t have to be enabled).

- Choose the Paint tool.

- Hold down Alt (Windows) or Option (Mac).

- While still holding down Alt or Option, click where you want the note to start, and drag right (dragging left doesn’t work), while dragging up or down.

- The further you drag to the right, away from where you started, the more notes you’ll generate.

Past a certain point, some notes will repeat before moving on to the next note. The repeating is most likely to happen when using scales with few notes, like a Major Triad. The repeating notes can be a fun effect with sounds that have a fast decay.

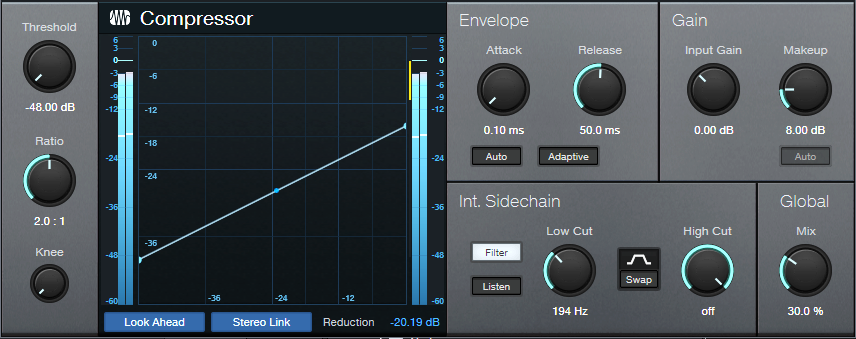

When doing arpeggios, I like to drag up to the scale note just before the octave, and then create a second, downward arpeggio (fig. 2). You can turn this into an Event, and hit D to create as many iterations of the arpeggio as you want.

Figure 2: An arpeggio created by stretching a chord shape up, then creating a second arpeggio that stretches the chord shape down.

Strum Fun

Let’s turn our attention to strumming. One of my favorite alternatives to a conventional strum is that you don’t have to strum from the top or bottom of a chord, you can strum from the “inside out.” It sounds more like fingerstyle picking than strumming.

- Create your chord of choice.

- Select all the chord notes.

- Click somewhere toward the middle of the note where the strum should end (fig. 3 shows what happened when I chose the middle of the 7 notes) and hold down the mouse button.

- While still holding down the mouse button, hold down Alt+Ctrl (Windows) or Option+Cmd (Mac), and drag left or right. This is a wonderful effect—try it!

Even better, we can take advantage of another new 5.5 editing feature. Set the end of the Event to where you want the notes to end. Select all the notes, right-click on one of them, and choose Musical Functions > Process > Extend to Note End. Now you’ll have a lovely, strummed attack, and all the notes will end at the same time.

More strum fun tips:

- You don’t need to strum all the notes of a chord. You can select, for example, just the top three chord notes, and strum those.

- Don’t overlook downstrokes. Click on the lowest note of a chord, hold the mouse button down, then hold down the Alt+Ctrl or Opt+Cmd and drag right. Now the top note will stay in place, and the strum will progress downward in pitch. If you want to end on the lowest note, choose the highest note instead of the lowest one, and drag left.

- Anyone who’s been following this blog knows I’m a fan of 12-string guitars and Nashville tuning. So, copy your strum, move it up an octave, and offset it slightly late compared to the original strum (see fig. 4, which once again takes advantage of the Extend to Note End function so that all the notes end at the same time).

Finally, it gets even better when you combine these techniques. For example, in fig. 4, you could strum the octave notes from outside in, and the lower notes from the inside out…or make one a downstroke, and one an upstroke.

Are we having fun yet?

“Melodify” Your Beats

Wouldn’t it be cool to add a harmonic element to beats? Well, thanks to Harmonic Editing and a little pink noise, you can. The goal is to have your beat or drum loop follow a chord progression, embed the percussive qualities into the chords, and then mix the desired blend of beats and chords. First, you need to do a little prep work:

Wouldn’t it be cool to add a harmonic element to beats? Well, thanks to Harmonic Editing and a little pink noise, you can. The goal is to have your beat or drum loop follow a chord progression, embed the percussive qualities into the chords, and then mix the desired blend of beats and chords. First, you need to do a little prep work:

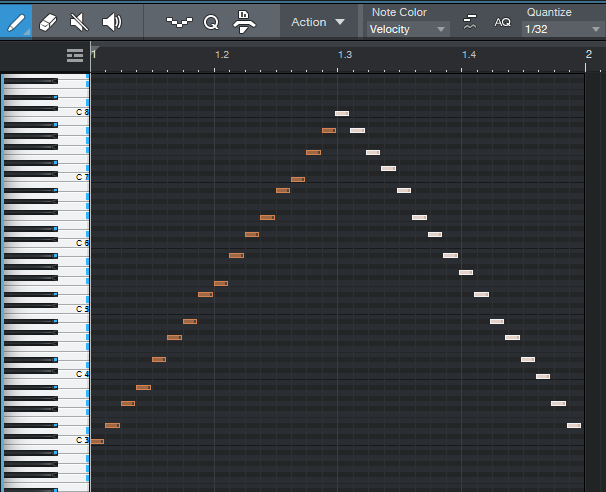

- Create a chord progression in your Chord Track.

- Add a track with a drum loop or drum part.

- Add a pink noise track.

How to Create a Pink Noise Track

- Insert the Tone Generator effect in a track.

- Set waveform to pink noise, level to -6.00, and then turn on the Tone Generator (fig. 1).

- Create an Event that lasts as long as where you want noise, by dragging the pencil across the pink noise track.

- Select the track in the track header, and choose Transform to Rendered Audio. Now you have a track of pink noise.

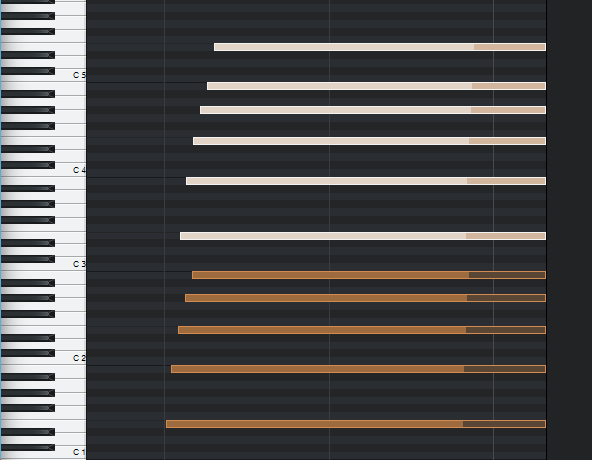

- Open the Noise Track’s Inspector, and for Follow Chords, choose Universal (fig. 2). The Tune Mode doesn’t matter.

Next, let’s have fun by blending the chords generated by the pink noise (from the Harmonic Editing) with the drums. Here are some examples.

Gate the Chords

Insert a Gate in the pink noise track. Send a sidechain from the drum track to the Gate. Adjust the Gate parameters so it triggers in sync with the drums (fig. 3).

Figure 3: Typical Gate settings for opening and closing the Gate in sync with the drums. Make sure Ducking is not enabled. Also, I EQ’ed the sidechain to inhibit the kick from triggering the gate, so that the noise track followed only the higher-frequency percussion.

Here’s what it sounds like—fun stuff!

Automating the Gate parameters can be useful, too (especially Release and Threshold).

X-Trem the Chords

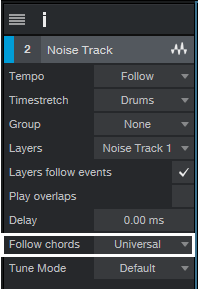

This sound inserts two X-Trems (fig. 4) in series in the pink noise track, and syncs them to tempo.

And here’s what they do to the beat…it sounds very reggae.

This is another application where automation can add a lot of variety—particularly by varying the LFO Speed parameter in the second X-Trem.

X-Trem + AutoFilter the Chords

Now try replacing the second X-Trem with an AutoFilter, set as follows (fig. 5).

This audio example plays only the chord part, and doesn’t mix in the drums. You can introduce a lot of mileage in a song by varying the mix of drums only, chords only, and drum+chords.

Have fun!

Cool Reverb Trick, Bro!

Let’s go right to the audio examples, because they’re worth a thousand words.

Let’s go right to the audio examples, because they’re worth a thousand words.

The problem: You want a big, lush reverb on drums. But that overpowers the drums, and turns them into a reverby mess…like this.

So sadly, you turn down the reverb, and give up your dream. But wait! Here’s the solution.

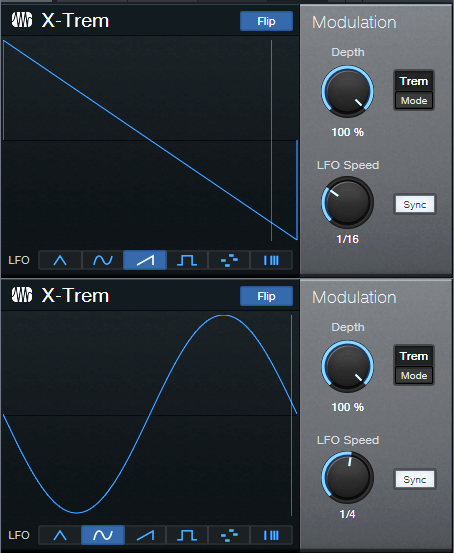

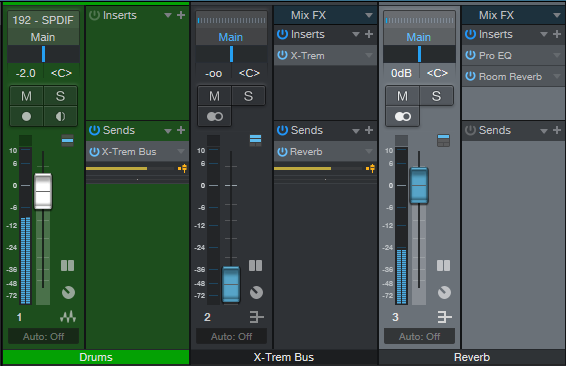

We haven’t changed the reverb settings at all, so there’s still plenty of reverb. But now it sounds tight, instead of like a reverby mess. The secret is creating a bus, and inserting X-Trem before the reverb (fig. 1).

You can ignore the Pro EQ, it’s there only because I usually insert a low-frequency rolloff prior to drum reverb (this prevents the kick drum from misbehaving). Fig. 2 shows the X-Trem settings. Make sure X-Trem and the drums are synced to the tempo.

Figure 2: The X-Trem is using sine wave modulation, set for 1/4 note sync. 1/8 note sync can also work well for faster tempos, and 1/4 for slower tempos.

If you have other tracks feeding the Reverb bus, you might not want them subjected to the X-Trem (or you might). If not, then see fig. 3.

Figure 3: How to apply this effect only to drums, when you want other tracks to feed the reverb bus.

Use a pre-fader send from the drums to a bus, insert the X-Trem in that bus and turn down its fader, then create a pre-fader send from the X-Trem bus to the Reverb bus. Now you can feed other tracks directly into the Reverb bus.

Cool reverb trick, eh?

Don’t Ignore the Free VU Meter Plug-In

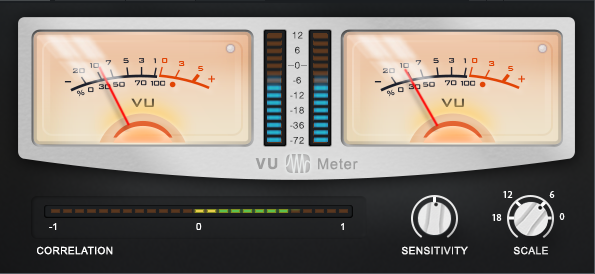

It may seem like VU meters are a relic of the past. However, the VU Meter plug-in that’s available for free in the PreSonus Shop is well worth the download—it’s more than just meter-based eye candy (fig. 1). This plug-in is particularly useful for mastering or as a master bus effect while mixing, because it shows several crucial aspects of a stereo mix.

Figure 1: This VU meter isn’t just free, it’s useful. Grab it before someone at PreSonus decides they should probably charge something for it.

The LED meters in the middle indicate peak signal levels, while the VU meters indicate average signal levels. These can provide useful clues about your music. If the average levels are high compared to the peaks, then there may be too much compression or limiting being used. Conversely, if the peak levels are high and the average levels are low, you may need some dynamics processing to even out the dynamic range somewhat.

The Sensitivity control acts like a damping control on the meters, where lower sensitivity averages out the readings over a longer time period. Turning up Sensitivity tracks the average level over shorter periods. Turning down Sensitivity for the slowest response provides a good way to compare average song levels, or sections within a song.

Scale correlates peak levels to your preferred amount of headroom. For example, for 18 dB of headroom, set Scale to 18. Then, signals that hit -18 dBFS will register as 0 on the meter. Setting Scale to 6 can be a good way to trick yourself into respecting headroom a little more, because signals at -6 dBFS will show as 0.

Finally, the Correlation meter indicates if there are any potential phase issues with stereo audio. A correlation reading of 1 means the audio is mono, or with stereo, that the audio in both channels is in phase. A correlation reading of -1 means the audio streams in the left and right channels are 180 degrees out of phase with each other (oops). Although it’s not a problem to dip into the red (negative reading) from time to time, if the readings are often negative, then phase issues may be a problem. These could be caused by an effect on a track that generates an out-of-phase output signal, stereo miking where the XLR cables were wired incorrectly (yes, it happens), or other gremlins. It’s generally best if the Correlation meter reading fluctuates between 0 and 1.

It never hurts to be able to get different perspectives on your audio, and this isn’t only a useful tool…it’s free, which is everyone’s favorite price. What’s more, if you have PreSonus Hub installed, you can also use the VU Meter with other VST/AU/AAX-friendly programs. And finally, let’s hear it for software—no matter how hard you hit the VU meter, you won’t break the needle!

Hit LUFS Targets with the New Digital Release Menu

It’s a streaming world—and streaming services have their own audio standards with respect to LUFS and True Peak levels. LUFS is not the same as peak or average loudness. Instead, it measures perceived sound levels. In theory, if two songs have the same LUFS readings—whether it’s Billie Eilish whispering or hardcore 1999 Belgian techno—you won’t feel the need to get up and adjust the volume.

True peak measures the peak value after D/A conversion, which can be higher than the peak value prior to D/A conversion. Having a peak value below 0 minimizes the chance of distortion when transcoding a WAV file into a data-compressed format. For more about LUFS, see Understanding LUFS, and Why Should I Care?

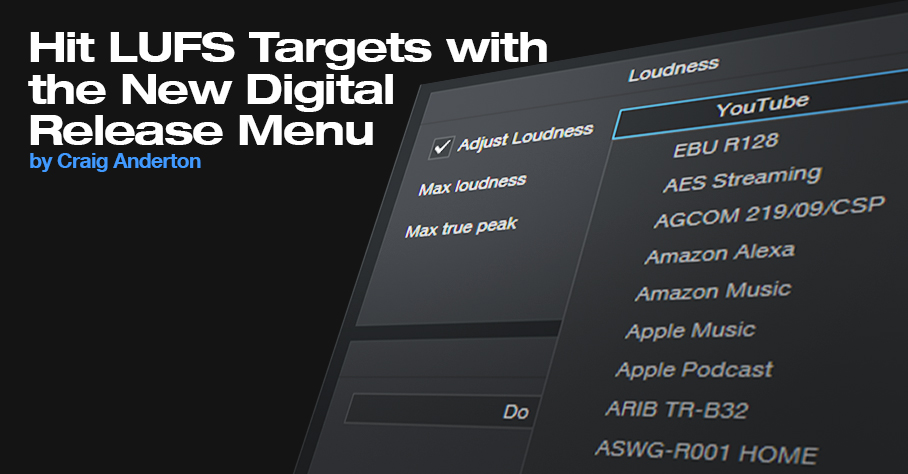

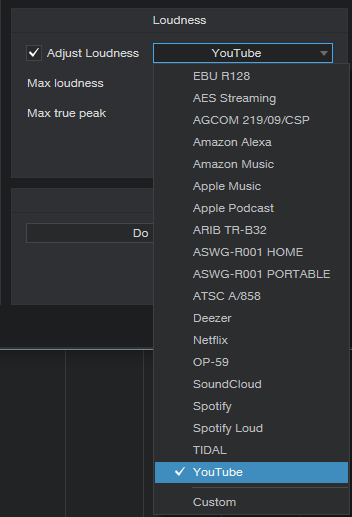

The Easy Song Level Matching tip tells how to use the Tricomp and Limiter to match song levels in a collection of songs or an album, and it remains viable. However, if you’ve already mastered your songs the way you like, Studio One version 5.5 has added an export function to the Digital Release menu that can export your songs to any LUFS and true peak level you want. What’s more, it includes presets for all the most popular streaming services (fig. 1).

Figure 1: To meet the specs for particular streaming services, simply choose a preset, and export. Here. YouTube has been chosen.

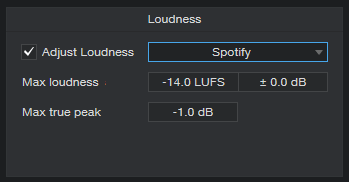

Another convenient aspect is that once you release the drop-down menu, you can see a particular streaming service’s recommended specs (fig. 2). This is also where you can specify custom settings for LUFS and True Peak.

Figure 2: Choosing a streaming service shows its desired file specs. This shows that Spotify wants files with a max loudness of -14.0 LUFS, and Max true peak of -1.0 dB.

Let’s do a real-world test to check the effectiveness. Consider two songs in the Project Page, one at -6.8 LUFS with a true peak reading of +0.7, and the other at -12.2 LUFS with a true peak reading of +0.1 (fig. 3). We’ll export them to Spotify’s standard mode, which wants -14.0 LUFS and -1.0 true peak, and then load them back into the Project Page to see what happens.

The -6.8 LUFS file had to be turned down a lot to hit -14.0 perceived level. Turning down the level lowers the true peak reading; in this case, it ended up at -6.5. The -12.2 LUFS file didn’t need to be turned down much at all to hit -14.0 LUFS, and its true peak reading is now -1.7. When played back, even though the waveform levels look very different, they sound like they’re at the same level.

However, it’s important to note that this process won’t raise the level if the peaks already hit 0. For example, if one of the files was normalized and its LUFS reading was -15.0, it wouldn’t have increased to -14.0 LUFS because that would have required processing (e.g., limiting) to raise the level. Otherwise, any peaks would have exceeded the headroom.

The export function simply does what most (but not all) streaming services do—turn down levels above the target LUFS to reach the desired LUFS reading. This makes sense, because the main reason streaming services adopting LUFS targets was to prevent songs that were mastered “hot” from having a level advantage over songs mastered with more reasonable (and more listenable) dynamics.

Figure 3: The two files on the left are the original files. The versions on the right now have LUFS readings of ‑14.0.

Finally, you don’t have to master everything to hit a specific service’s specifics, because this new Studio One function does it for you. Master the music so it sounds good to you—go ahead and compress that rock track, or maximize an EDM set. If it has the right sound but its LUFS reading is -9 or whatever, don’t worry about it. When you export it to a specific target, the song will meet that service’s specs.

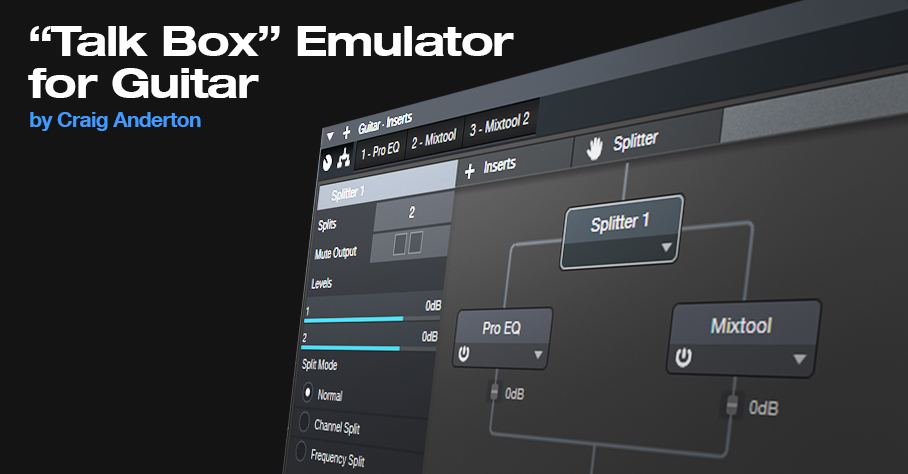

“Talk Box” Emulator for Guitar

Although this isn’t an actual talk box, it does give humanized mouth sounds with Studio One Professional. This is possible because the human mouth is a filter, and Studio One has filters…so let’s do it! Check out the audio example, then download the .multipreset to try it out for yourself.

Talk Box.multipreset – Click to download

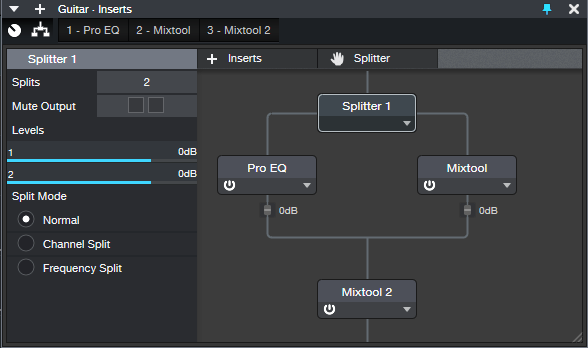

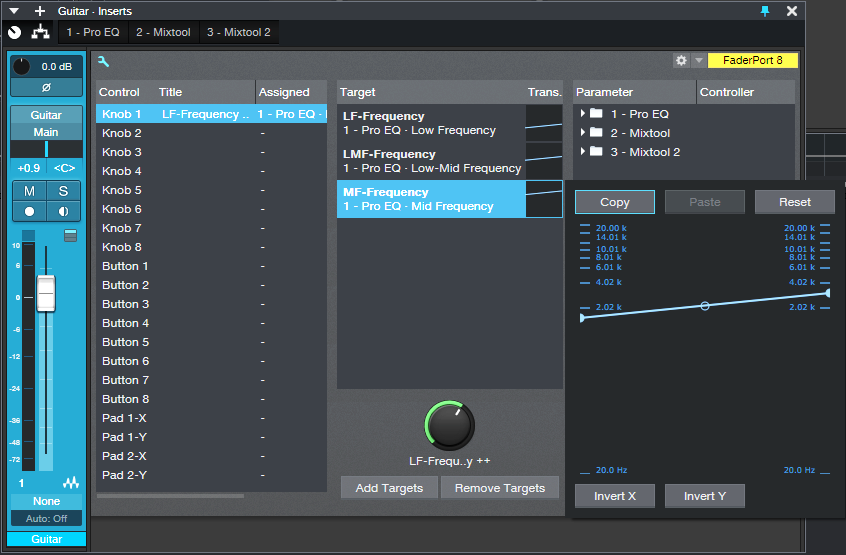

The Talk Box works by splitting the guitar (fig. 1). One split goes to a Pro EQ2, which uses a Channel Editor knob to sweep three bandpass filters simultaneously over the vocal range. The other split goes through a Mixtool that flips the phase, so it cancels all the audio from the Pro EQ2 except for the bandpass filter peaks.

EQ Settings

The Pro EQ2 uses three stages (fig. 2). The LF stage, in Peaking mode, sweeps from about 250 to 500 Hz. The LMF stage sweeps from around 750 Hz to 1.5 kHz, while the MF stage sweeps from 1.5 to 3.0 kHz.

Channel Editor Settings

Use the Channel Editor to assign the filter frequencies to a Macro control knob (fig. 3).

Figure 3: The Macro knob’s range has been edited to cover the Mid Frequency stage’s frequencies. Edit the other targets similarly

The second Mixtool at the output increases the level by 6 dB. This is necessary because one of the splits is out of phase. Because only the filter peaks come through, the output level is considerably lower than the input.

Everything described so far is included in the multipreset, but assigning the Macro knob to a MIDI controller or pedal is up to you. I did a blog post on a way to do this, and the information is also in The Huge Book of Studio One Tips and Tricks. (A heads-up for current owners of the book: a free update will be available soon with more tips, presets, and content, so stay tuned.)

Just remember that you can’t automate the Macro knob per se. You’ll need to add three Automation tracks, assigned to the Low, Low Mid, and Mid frequency parameters. Then, make sure they’re in Write mode when you move the Macro knob control, and they’ll automate the “talk box” changes.