Category Archives: Friday Tip of the Week

Komplete Kontrol Integration in Studio One, Part 2/3: General-Purpose MIDI Control

In Part 1 (“A New Hope”) of the NI Kontroller trilogy, we covered how to integrate the DAW functions from Native Instruments’ Komplete Kontrol keyboards with Studio One. Let’s take this another step further.

In theory, Komplete Kontrol’s MIDI control surface application is only for stand-alone use, and requires using both an external power supply and the keyboard’s 5-pin DIN MIDI connectors for I/O. With a live rig, this makes sense; for use with a DAW, you have the NKS spec communicating over USB. But wouldn’t it be great to be able to use the Komplete keyboard’s control surface with non-NKS instruments, and even effects, in Studio One over USB? Well, you can.

GETTING STARTED

For Windows, install MIDI-OX. This utility is key to letting us re-direct the MIDI messages at the Komplete keyboard’s external output to Studio One.

For Macs running Catalina, I currently don’t know of any way to use the MIDI Patchbay utility. This is similar to MIDI-OX, but hasn’t been updated since 2008, and system requirements stop at Mac OS X 10.14. You can try using it with pre-Catalina systems; if Apple’s Gatekeeper blocks the installation, you’ll need to allow it under Security & Privacy. Once you get it installed, it should work similarly to MIDI-OX if you choose Komplete Kontrol S-Series Port 1 for the MIDI input option (and consider that equivalent to Komplete Kontrol -1 in the following description), and choose Komplete Kontrol S-Series Port 2 for the MIDI output option (it should work similarly to Komplete Kontrol EXT-1, below). Mac users, please feel free to comment below about what does and does not work with the Mac.

Back to Windows…

- Turn on the Komplete keyboard.

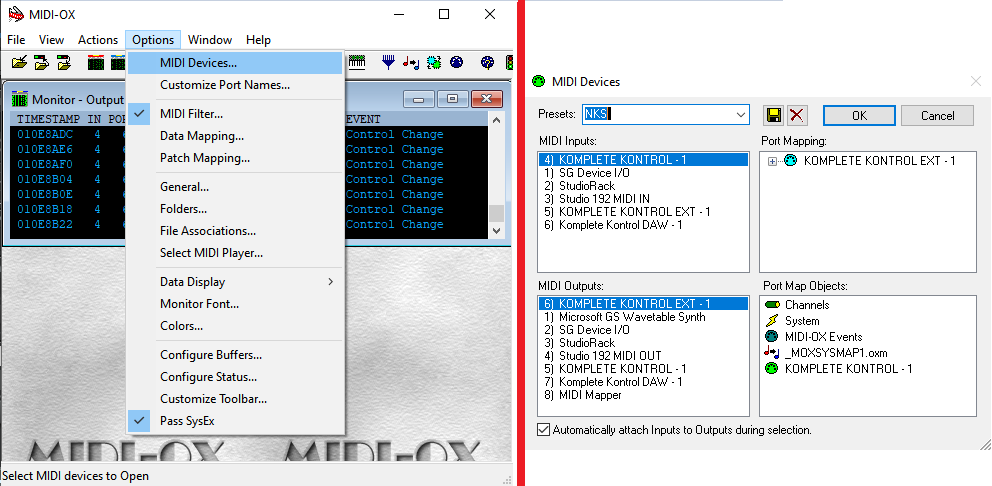

- After the keyboard boots, open MIDI-OX. Under MIDI-OX’s Options > MIDI Devices, choose Komplete Kontrol – 1 for MIDI Input and Komplete Kontrol EXT-1 for MIDI output (Fig. 1). Click OK to close the MIDI Devices screen.

- Open Studio One, but leave MIDI-OX open while Studio One is open.

Figure 1: How to set up the MIDI-OX utility so that NI keyboards can control non-NKS instruments over USB.

- Now we need to tell Studio One that MIDI-OX is a new keyboard, even though it isn’t really. Choose Studio One > Options > External Devices, click Add, and choose New Keyboard (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: How to add MIDI-OX as a pseudo-keyboard.

- For Receive From, choose Komplete Kontrol – 1. Studio One will warn you not to do this, but just ignore the warning. For Send To, choose Komplete Kontrol Ext – 1. You’ll have another warning to ignore—but I promise you, no harm will come to Studio One.

- Click OK, then click OK again to get out of the options screen. We’ll cover when/how to use MIDI-OX later.

A WORD OF CAUTION

At the moment, the Komplete Kontrol application’s template management is somewhat primitive. Any changes you make are saved when you close the MIDI controller application; there’s no “Save” or “Save as” command, nor can you manage individual templates—they’re all saved in a single .dat file.

However, if saving-by-closing doesn’t work for you, and you can’t seem to save new templates, there may be an esoteric Windows problem. This is particularly likely for those who upgraded to Windows 10 from an earlier version, because the folder holding the templates may be write-protected due to inheriting permissions. Here’s the fix.

- Open the C: ProgramData folder. (This is a hidden folder, so if you don’t see it, type Windows key+R, and then type Control Panel in the Open box. In the Control Panel, click on Appearance and Personalization, then choose File Explorer Options. Click on View, and then select Show Hidden Files, Folders, and Drives.)

- In ProgramData, locate the Native Instruments folder, and right-click on it.

- Click on the Security tab, then click Edit.

- Choose Users, check all the Allow boxes, and click Apply. Also, do this for any other Group or User names that let you click the Allow boxes (Creator Owner may not…no worries). After applying everything, click OK.

Okay, now that’s out of the way. Hey!! Don’t blame me! It’s a Windows thing.

CREATING A STUDIO ONE-FRIENDLY TEMPLATE

You access the MIDI control surface when you push the Komplete keyboard’s MIDI button, which also defaults to opening if the Komplete keyboard doesn’t see an NKS instrument. The following procedure describes how to create the kind of template we want for Studio One’s plug-ins.

- Open the Komplete Kontrol application (Komplete Kontrol.exe) in stand-alone mode, not as a plug-in. This is the only mode that lets you do MIDI assignments. Then, click on the MIDI 5-pin DIN symbol in the upper right (Fig. 3).

- Create a new template by clicking on the + button under templates. Right-click on it to rename it.

- The template will default to two pages of controls (16 knobs total), but of course, we want more! Click on the + sign to the right of a page, and you can add up to two more pages.

Figure 3: The important items needed to create and customize a template are circled in white. From right to left: MIDI button that opens the MIDI assignment editor, + sign for adding more pages, and + sign for adding more templates (in this case, it’s adding one for the Fat Channel).

- Now comes the tedious part. Each knob and button needs to have a unique MIDI continuous controller (CC) number, so that each one can control a unique parameter. Page 1 defaults to CC14-CC21, and page 2 covers CC22-CC29. However, pages 3 and 4 just duplicate the assignments for page 1, and all the buttons default to CC112-CC119. So it’s time to program some additional controls.

- Click on one of the virtual knobs, and you’ll see its number assignment in the MIDI field toward the lower middle. Change this number to the desired controller number. The label will still reflect the old number, but that’s okay—we’ll be re-naming the labels anyway for specific synth and effects parameters. Here’s how I assigned the controllers.

Knobs

- Page 1: 14-21 (the default)

- Page 2: 22-29 (the default)

- Page 3: 30-37

- Page 4: 38-45

Switches

- Page 1: 88-95

- Page 2: 96-103

- Page 3: 104-111

- Page 4: 112-119 (the default)

Note that you can choose whether the knobs cover an absolute range, as specified by the Range From and To controls, a Relative Range, or a Relative Offset. Since I don’t like my head to explode any more than necessary, I left this option on Absolute to start, knowing that I could change it later. You can also program keyboard parameters, pedals, the touchstrip, and the keyboard key colors—16 color choices in all. So, different templates can color the keys differently for visual confirmation that you’ve chosen the desired template (of course, I chose the color “mint” for the Mojito template).

So to recap, we’ve set up a general-purpose template, with a separate controller for each knob and switch, that we can use to create a custom control surface for non-NKS instruments and effects… as we’ll find out in part 3 of the NKS trilogy, Rise of the Controller.

Komplete Kontrol Integration in Studio One, Part 1/3

Studio One 4.53 introduced integration with Native Instruments’ Komplete series of keyboards, which is a big deal. Although these keyboards are theoretically dedicated to NKS-compatible plug-ins and mixer/transport hands-on control, with Windows systems (Mac fans, there’s more on this later) you can use the keyboard as a general-purpose, hands-on MIDI controller for non-NKS plug-ins, including all bundled PreSonus effects and instruments (as well as plug-ins from other manufacturers). Also, unlike standard NKS, you’ll be able to control effects, regardless of whether or not they’re inserted in an instrument track.

There’s a lot to cover, and since this is more like a tutorial than a tip, it’s split into three parts: DAW control with Studio One, creating custom templates for plug-ins, and how to apply the templates in your workflow.

INTEGRATING THE KEYBOARD

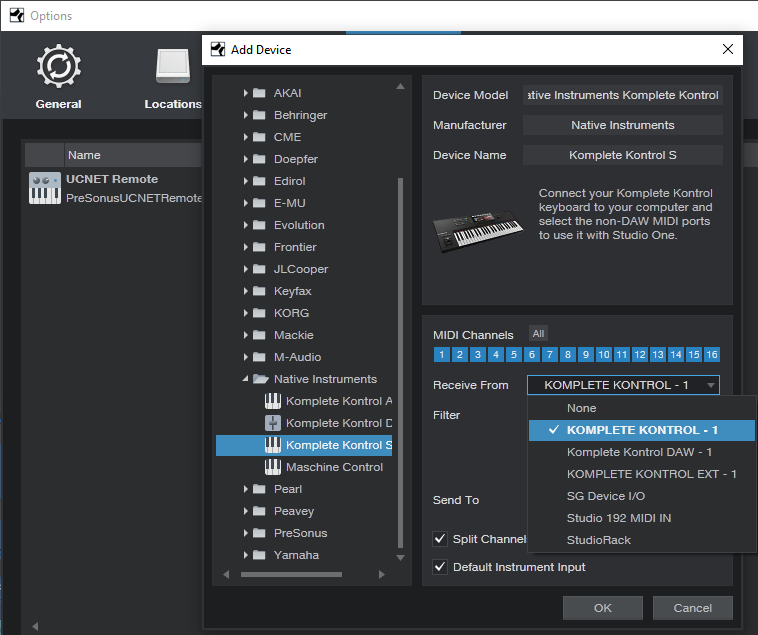

Choose Studio One > Options > External Devices, and click Add. Scroll to the entry for Native Instruments, unfold it, and select either your A/M or S series keyboard for Receive From and Send To. I’m using an S49 (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Komplete is selected as the keyboard, with Split Channel selected for more convenient use with multitimbral instruments, like IK Multimedia’s Syntronik.

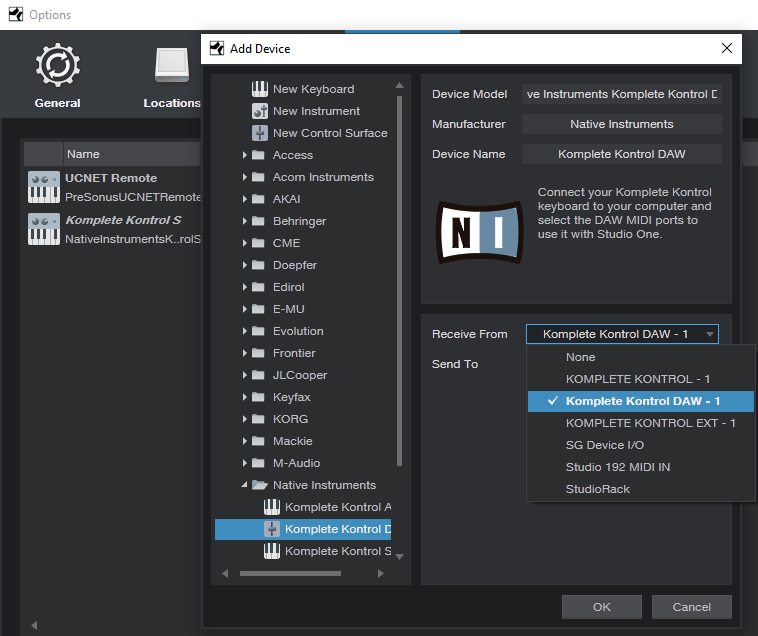

INTEGRATING THE CONTROL SURFACE

Now let’s set up the Komplete keyboard as a new control surface. Again, choose Studio One > Options > External Devices, click Add, and scroll down to the entry for Native Instruments. Unfold it, and select Komplete Kontrol DAW – 1 for both Receive From and Send To (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: How to add the Komplete keyboard as a control surface for DAW integration.

CHOOSING THE MODE OF OPERATION

To edit NKS plug-ins, press the PLUG-IN mode button in the keyboard’s cluster of six buttons, toward the upper right. Controls that don’t relate to a synth or effect, such as the Transport, Metronome, Tape Tempo, and the like remain active. When it’s time to mix and you want full integration with Studio One’s mixer, press the MIXER button.

The following describes how the control surface for the current S-series Mk2 keyboards integrates currently with Studio One; click here for information from PreSonus on suitability with other NI keyboards, and updates.

Transport. The Play, Rec, and Stop buttons do what you’d expect, but there’s more to the story than that—there are several nuanced options. The following assumes you’re starting from a stopped transport.

- Press Play to begin from the Play Start marker. If there’s no Play Start marker, playback starts from the cursor’s current position. If you stop and re-initiate playback, playback re-starts from the cursor’s original position.

- Return to zero: When the transport is stopped, press Stop again to return to zero.

- Pushing on the big navigation knob toward the right initiates playback from the Play Start marker. (Note that this involves pushing downward into the knob, not left/right or up/down.) If there’s no Play Start marker, playback begins from the Loop Start, whether the loop is active or not.

- Push downward on the navigation knob during playback to jump to the Loop Start, which resumes playback automatically from there.

- Pressing Shift+Play operates the same way as using the navigation knob for playback control.

- With any scenarios involving the Play Start marker, it doesn’t matter if it’s before or after the Loop Start, or within the loop itself.

- Press Rec to initiate or punch-in recording. Press again to end or punch out recording. If you don’t record audio or MIDI while recording is active, there’s no blank event—it’s like nothing ever happened.

- Shift+Rec toggles the count-in between on and off. When you press Shift and count-in is enabled, the Rec button letters light bright red. Otherwise, the rec button letters are dimmed.

- Loop toggles the loop between on and off. To move the loop (whether enabled or not), hold the Loop button down, and rotate the navigation knob. For example, if the loop extends for four measures, moving the knob 1 click clockwise moves the loop forward to the next four measures. Moving the knob 1 click counter-clockwise moves the loop backward to the previous four measures.

- Metronome toggles between on and off.

Mixer

- The display for each visible channel shows the channel’s name, fader level, pan, metering (but not overloads), and status of a channel’s Record, Solo, and Mute buttons.

- Track select buttons. The eight buttons above the display select a track, however, moving the navigation dial left or right moves from one track to the adjacent track (left or right respectively).

- Hold Mute, and then select a channel with its track select button, to mute/unmute. The keyboard’s corresponding select button glows yellow.

- Hold Solo, and then select a channel with its track select button, to solo/unsolo. The keyboard’s corresponding select button glows blue.

- Shift+navigation knob move down (not push inward) selects level for the selected track. This mode remains selected until changed. Both the associated track knob, and the navigation knob, alter the selected track’s level. Holding Shift while moving either knob provides finer resolution. The individual track knobs provide the finest resolution.

- Shift+navigation knob move up (not push inward) selects pan for the selected track. This mode remains selected until changed. Similarly to level selection, both the track knob and navigation knob alter the selected track’s pan, and holding Shift while moving either knob provides finer resolution. The individual track knobs provide the finest resolution. Note: The Pan control for the Main channel is always shown panned full left. You can ignore this, because the Main channel doesn’t have a pan control anyway. The pan is centered properly.

- Auto toggles between Read and Touch (write) automation for the selected track. Be aware that you can’t choose automation off with Auto.

- Left/right arrow buttons select channels in groups of 8. However, if the last bank of eight has fewer than eight channels, the display will fill with the last eight channels. For example, if you expect the last bank to be channels 17-24 but only 22 channels are in use, the keyboard will display channels 15-22. This is by design, because it makes sure there aren’t any blank channels—you can always see eight channels at a time. If you hit the left arrow button, it won’t go back to channel 9, but be offset by the same amount as the previous bank. To “reset” the banks, hit the left arrow button until you’re back at the beginning.

Miscellaneous Functions

- Undo and Redo. For Redo, hold Shift and press Undo.

- Quantize. This quantizes whatever is selected, at the current quantize value.

- Tap this, even if not lit, for tap tempo. I love this feature when starting a song.

This takes care of the mixer and transport functions. Next week, we’ll cover how to create custom MIDI control setups using the Komplete Kontrol application, and that will prepare us for Part 3, which describes how to create “faux NKS” control surface capabilities for PreSonus instruments and effects. Yes, it really is possible…

How to Play Faster—By Playing Slower

In the comments for last week’s tip on varipseed-type formant changes, reader Randy Hayes asked if it was possible to change the tempo similarly so that you could play along with something at a slower tempo, then speed it back up (while still being the correct key). This was a common technique with tape, but because pitch and speed were locked together, there would be formant changes—whether you wanted them or not—when you returned the slowed-down track to pitch.

One of the MIDI’s great features is that you can sloooooooow down the tempo, play along with the slowed-down track, then speed it up to make it seem like you have lightning-fast technique. The good news is that with audio, you can slow down Studio One’s tempo without changing pitch, which sounds great in theory. The bad news is that this isn’t always a painless solution, because Events recorded at a slower tempo will likely need to be time-stretched when you return to the original tempo, and you may also need to call up the Inspector for Events or Tracks to specify how the Events should relate to tempo. Also, if there’s a Tempo Track with tempo changes, then you have to offset all the tempo data, as well as make sure you restore it to the proper tempo when you’re done.

Fortunately, there’s an easy way to record along with a song at a slowed-down tempo, and have the correct timing for the recorded part when you restore the song to its original tempo. This complements last week’s formant-changing trick; the technique starts off similarly but ends up quite differently.

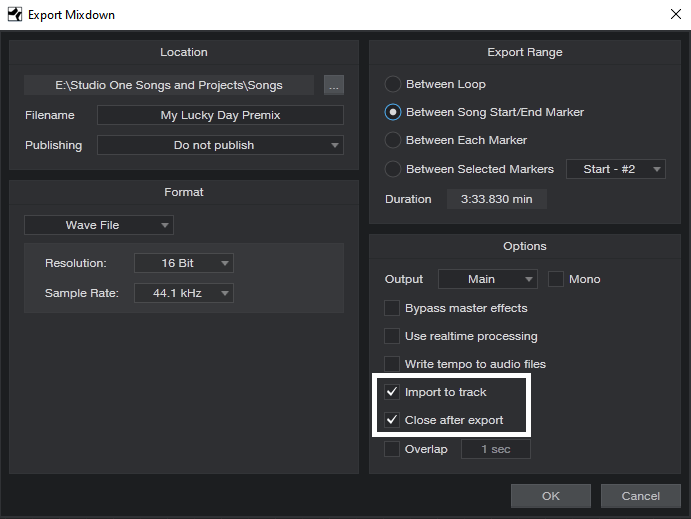

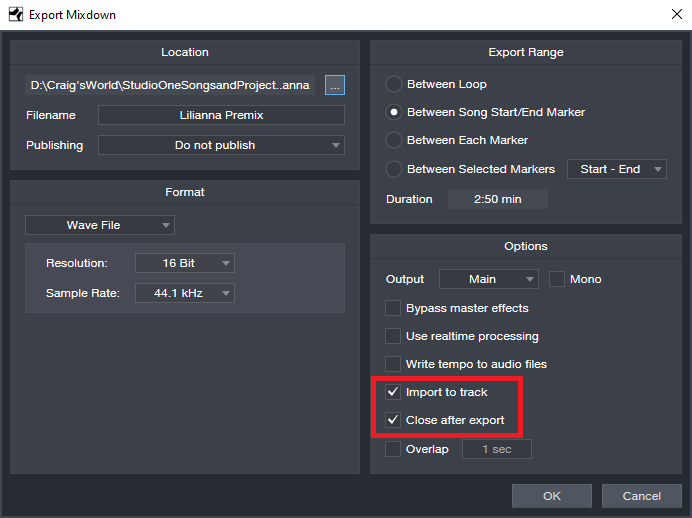

- Create a premix of your existing tracks with the Export Mixdown function. In the dialog box, check Import to Track and Close after Export (Fig. 1; outlined in white).

Figure 1: Use the Export Mixdown function to create a premix.

- After the premix is imported, mute all other tracks except for the Imported premix track.

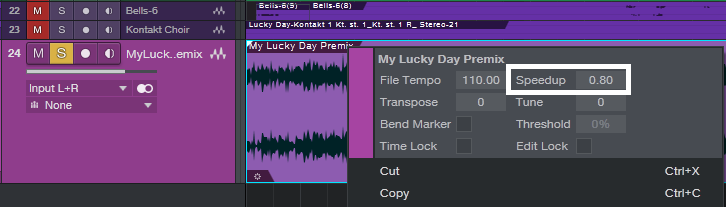

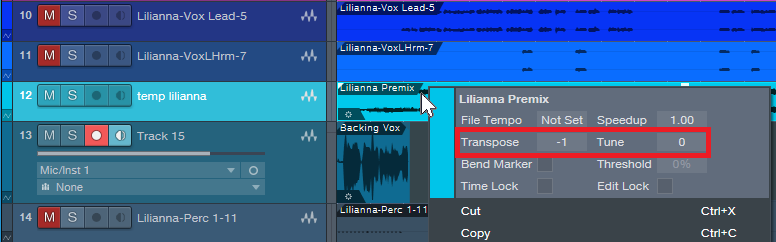

- Select the premixed track, and right-click on it (Fig. 2), or open its Inspector (F4), to access the Speedup parameter. Note that this parameter can also slow down the speed, by entering a value less than 1.00.

Figure 2: Access the Speedup parameter by right-clicking on the premix.

- Slow down the premix to the desired tempo with the Speedup parameter. For example, a Speedup reading of 0.80 means the song’s tempo is 80% as fast as it had been previously. Bear in mind that you can’t do a ridiculous amount of slowing down without affecting the audio quality of the track you’re recording, but overall, Studio One is quite forgiving.

- Record the new track as you listen to the premix’s slowed-down tempo.

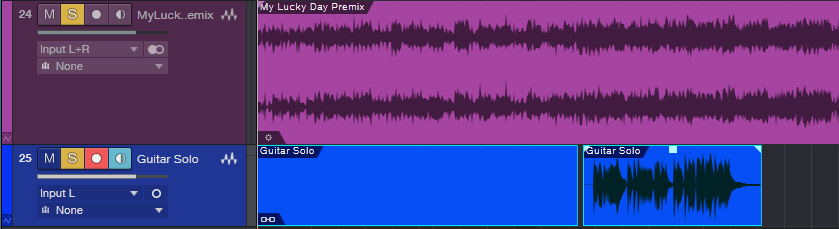

- Before restoring the original tempo, the track you recorded has to start at the song’s beginning. If that’s where you started recording, fine. Otherwise, use the Paint tool to draw an Event between the start of the song and the start of your part, select them both, and type Ctrl+B to merge them together (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: The recorded guitar solo, with an added “dummy” Event that starts at the beginning of the song, prior to merging them together.

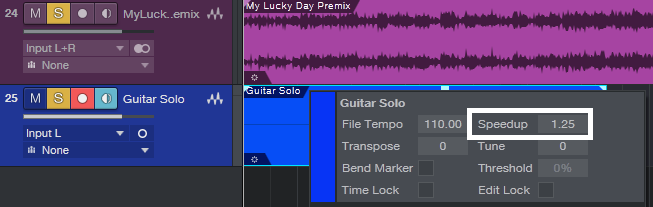

- Now, right-click on the overdub you recorded so you can access its Speedup parameter.

- Open up your calculator to determine how much you need to speed up the overdub. Divide 1 by the slowdown amount to obtain the correct Speedup amount. For example, if you slowed down to 0.80, then 1/0.80 = 1.25. So, set the recorded track’s Speedup parameter to 1.25 (Fig. 4).

Figure 4: Once the newly recorded track goes to the start of the song, change the Speedup parameter to compensate for the slowdown.

- Delete the premix (or mute it if you plan to do more recording at the slower tempo), and unmute the other tracks. The part you recorded should now match the Song’s overall tempo, even if there are tempo changes.

Note that any vibrato will be sped up when you restore the new part to the original tempo. This may be something you want, but if not, just remember to apply a slower vibrato than usual. Also, the timing will be tighter—a note that’s off the beat by a bit will hit closer to the beat when sped up.

Sure, some people might think this is cheating. But back when recording studios started adding EQ or reverb to vocalists, that was considered cheating too. The technique is the skill with which we use our tools, and having “Studio One technique” can be just as important—and valid—as having technique on your chosen instrument.

Just remember, all that matters about music is the emotional impact on the listener. They don’t care what you did to produce that emotional impact!

Varispeed-Type Formant Changes

Back in the days of tape, when dinosaurs ruled the earth and gas station attendants checked your oil, variable-speed tape recorders allowed changing the pitch of all the tracks with a single control. This was useful for many applications. The most common were speeding up masters a bit to make them a little brighter and tighter, doing tape flanging, and perhaps the most popular, changing vocal formants. If you transposed the recorder’s pitch down a little bit, recorded a vocal as you sang along with the lower pitch, and then transposed back up again on playback, the vocal formant would be higher and brighter. Similarly, for a darker, warmer sound, you could transpose up, sing along with that, and transpose back down again. The same principle worked with other instruments, but vocals were the most popular candidates for this technique.

The main limitation (although it could also be an advantage in some situations) is that the tempo and pitch were interdependent—a higher pitch meant a faster speed, and a lower pitch, a slower speed. This was useful for masters, because you could speed up and brighten a track by upping the speed by 2% or so. The Friday tip for June 8, 2018 covered how to emulate true, variable speed tape effects when working on a final stereo mix.

A major advantage of today’s digital audio technology is that pitch and tempo can be independent, and one of Studio One’s attributes is that the audio engine retains its sound quality with reasonable pitch changes (e.g., a few semitones). This makes it very easy to do the old tape trick of changing vocal formants; here’s how.

- First, create a premix of your existing tracks with the Export Mixdown function. In the dialog box, check Import to Track and Close after Export (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Use the Export Mixdown function to create a premix.

- After the premix is imported, mute all other tracks except for the Imported premix track.

- Select the premixed track, and right-click on it (Fig. 2), or open its Inspector (F4), to access the Transpose and Tune parameters.

Figure 2: You can access the Transpose and Tune parameters by right-clicking on the premix.

- To brighten the vocal formant, use the Tune and/or Transpose function to lower the pitch.

- Record the vocal track as you listen to the premix.

- After recording the vocal track, right-click on the vocal Event, or open its Inspector, and tune it up by as much as you tuned the premix track down. For example, if you tuned the premix down a semitone, tune the vocal track up a semitone.

- Delete the premix (or mute it if you plan to do more formant-shifted tracks), unmute the other tracks, and enjoy your formant-shifted vocal.

This is especially useful when doubling parts, because the double can have a slightly different timbre. And with background vocals, shift some formants up, and some formants down, for a bigger, more interesting sound. And of course, if you just can’t quite hit that high note…you’re covered. I promise I won’t tell.

I also like using this with guitar and other instruments. I’ve gotten away with pitching guitar up 7 semitones for a bright sound that splits the difference between a standard guitar sound, and one that’s more like “Nashville” tuning (as described in the Friday Tip for December 1, 2019). At the other end of the tonal spectrum, playing along with the premix tuned up, and pitching back down, is like using a low tuning on a guitar—great for those massive metal guitar sounds.

—————————————

As we enter 2020, thank you very much for your support of these blog posts, and your comments. Also, thank you for supporting the Studio One book series that I’m writing. When I wrote the first book, I wondered if there would be any demand for it, or whether I was just wasting my time. Well, you’ve answered that question… so now I’m working on book #5 of the series, about how to record great guitar sounds with Studio One. It won’t be done for a while, but it wouldn’t have been done at all without your support (or the great-sounding new amp sims, for that matter).

Finally, let’s all thank Ryan Roullard and Chad Schoonmaker, who wrangle the blog and social media each week to get this blog posted and promoted. It’s not like they don’t already have enough to do at PreSonus, which makes their involvement just that much more appreciated. Thanks guys!

Bi-Amping the Ampire

I’m still wrapping my head around PreSonus giving us amp sims that are light years beyond the original Ampire in a free update…and also making them available for use in other programs. But now that they’re here, let’s take advantage of them before PreSonus’s accounting department changes its mind.

The new amp sims do not supplement the old Ampire, but replace it. New Studio One owners will have only the new amps; existing users will find that the legacy presets were removed. If you need to get the older presets back because you used them in pre-4.6 projects, simply install the Ampire XT Classics extension—but I’d recommend redoing any presets with the new amps, because they sound so much better. (The Ampire XT Metal Pack works with the new Ampire, but you may need to re-install it.) The PreSonus Knowledge Base has an article with everything you need to know about making the conversion from the old Ampire to the shiny new Ampire XT.

Why Bi-Amp?

Bi-amping a guitar amp is useful for the same reason that most studio monitors are bi-amped—just as you can optimize the speakers for high and low frequencies, you can optimize the amps for high and low frequencies. For example, with heavily-distorted chords, the high strings will be equally distorted and relatively indistinct. With bi-amping, the lower notes can have a big, beefy distortion sound, while the high notes ring out on top—which is the subject of this Friday tip.

Let’s take a bi-amped preset apart to find out how it works. This preset is available on the PreSonus Exchange, so if you just want a cool, crunchy rhythm sound, go ahead and download it. But the real value here is learning how to make your own presets, because this preset was made using my guitar, pickups, strings, playing style, pick, and follows my musical tastes. It’s unlikely you play guitar in exactly the same way, so it’s worth tailoring any amp sim preset—not just this one—to your own playing style and gear.

Recording the Guitar

Guitars are mono, but to play stereo games, we need to convert a mono track to dual mono. This allows using processors like the Binaural Pan.

- Record a mono guitar track with Channel Mode set to Mono.

- Change Channel Mode to Stereo.

- Select what you recorded.

- Choose Bounce Selection (ctrl+B). Now your guitar part is dual mono (e.g., the same part in both the left and right channels), so Studio One recognizes it as stereo.

The FX Chain Multipreset

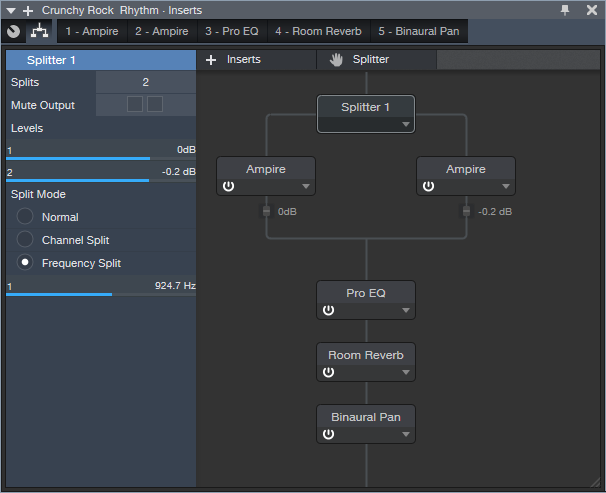

Fig. 1 shows the FX Chain “block diagram.” The Splitter is doing a Frequency split; frequencies below 924.7 Hz go to the left split, while frequencies above that go to the right split.

Figure 1: Bi-amp Multipreset block diagram.

Next up is choosing the amps, and setting their parameters (Fig. 2). The left split uses the MCM 800, a revered British amp that can marshall its resources to give big, beefy sounds. The right split’s VC30 amp is known amongst the vox populi for its bright, ringing high end, so the two amps are ideal for delivering the desired result.

Figure 2: Left split (on top), right split (below).

Now let’s enhance the amp sound with some EQ, reverb, and stereo imaging to spread out the reverb a bit more (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: Final touches for the bi-amp multipreset.

The EQ adds the equivalent of an amp’s “bright” switch. With a non-bi-amped preset, you have to be very careful about adding brightness because it can emphasize any artifacts caused by intermodulation distortion. But that’s not an issue here, because of the VC30’s a clean high end. The gentle low-frequency roll off simulates more of an open-back cabinet sound. The reverb is sort of a cross between a spring and room sound, while the Binaural Pan spreads out the reverb signal for a wider stereo image. The pan setting is fairly conservative; feel free to widen things further.

This multipreset makes an excellent template for further adventures with bi-amplification. Of course, this just scratches the surface of what’s possible with these new amps—so stay tuned to the Friday Tip of the Week for more applications.

Download the Crunchy Rock Rhythm preset here!

The Vinyliser FX Chain

Nostalgic for vinyl? Miss the glorious sound of dragging a rock through yards of plastic, the wild frequency response gyrations of analog RIAA curve filters, the surface noise from recycled vinyl, scratches and pops from dust particles, inner groove distortion, sound quality deterioration over time, and warpage from records not being stored properly?

Well, I don’t miss it at all. But, recently I needed to sample a loop from a song that had been recorded with (of course) pristine quality in Studio One, and apply a trashification process to make it sound like the loop was taken from an old, abused, and never cleaned vinyl record. The object was not to come up with an FX Chain like the existing plug-ins that aim to emulate vinyl’s better qualities, but instead, something that could emulate some of vinyl’s worst qualities.

Now, you might think it would be easy-peasy to take something good and make it sound bad, but it’s not—because vinyl is/was a very specialized form of bad, and reproducing that inside of Studio One is a challenge. But we tackle the tough gigs here in the Friday Tip! Here’s what I learned.

Hissy that Fits

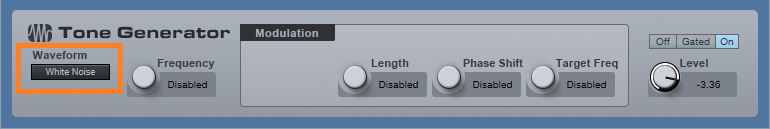

Figure 1: The Tone Generator’s white noise output is pretty much all we need for hiss, whether tape hiss or preamp hiss.

The really old vinyl stuff was pre-noise reduction, so we need some hiss. That’s easy: use Studio One’s Tone Generator (Fig. 1), set it for white noise, and keep the level down in the final routing.

Distortion

Figure 2: Each of these distortion processors gives a different kind of dirt flavor…try them both.

Simulating inner groove distortion isn’t necessarily easy, but we have a couple options (Fig. 2). The Softube Saturation Knob, set for Keep Low and a fair amount of distortion, will do the job when you’re in a hurry. If you have time to tweak, RedlightDist has much to offer. I like one stage of OpAmp distortion as shown, but you can also increase the distortion, or try different flavors. Some timbres even come close to tape-based distortion.

Warp that Record!

Figure 3: Setting the Analog Delay for vibrato, with no dry signal, emulates the pitch variations caused by a warped record.

The Analog Delay (Fig. 3) is ideal for warpage, because of its ability to do a slow vibrato. Choose a Sine wave speed of 1.33 Hz for a 33-1/3 LP, or 1.80 Hz for a 45 RPM single. Set Feedback to 0.0%, Width to Mono, and 100% for the Mix.

With 1.75 ms of initial delay (a/k/a Time), pushing the Mod amount up to 50% seems like enough warpage for most rational people. However, if you left your record out in the sun, in a car, with the windows closed, while you were at the beach, you can warp the virtual vinyl even further by increasing the initial delay time.

The Analog Delay has a couple of extras that help our cause. Turning up Low Cut and turning down High Cut can give a more lo-fi effect, like the sound is playing back from a portable record player or the like. Turn up saturation as well, because for nasty vinyl sounds, you can never have enough distortion.

Vinyl Surface Noise

I tried, I really did, to do this exclusively within Studio One. The closest I came was following white noise from the Tone Generator with the Gate, setting its Attack/Release/Hold controls to minimum, and editing the Threshold to let through only the very highest, occasional noise peaks. Adding a little high-end shelving EQ helped, as did using X-Trem in pan mode to move the clicks and pops across the stereo field, but ultimately it sounded more like cooking mini digital popcorn than funky scratches.

Admitting defeat, I went to 99Sounds.org (a fine source for unusual, 100% royalty-free samples), and found a section with vinyl noise SFX recorded by Chia. There are 37 samples, a few of which are over-the-top scratchy, but samples #12 and #29 were good for what I needed.

Routing

Figure 4: Routing for the Vinyliser effect.

For setup, the three different elements feed into a single FX Channel (Fig. 4), all through pre-fader sends. The original loop has the RedlightDist inserted to create the distortion; the vinyl surface noise samples have their own track (with a Pro EQ to boost the highs a bit); and the hiss has its own track as well. The Analog Delay in the FX Channel warps everything.

So does it sound any good? Of course not! But that’s the whole point…check out the audio examples, with before-and-after for a drum loop, and another for program material (with a more drastic effect than the drums).

Track Matching with the Project Page

Okay, this is an unusual one. Please fasten your seat belts, and set your tray tables to the upright and locked positions.

Personal bias alert: With pop and rock music, for me it’s all about vocals, drums, and bass. Vocals tell the story, drums handle the rhythm, and bass holds down the low end. For a given collection of songs (formerly known as an “album”), I want all three elements to be relatively consistent from one song to the next—and that’s what this week’s tip is all about. Then the other instruments can weave in and out within the mix.

It’s fantastic that you can flip back and forth between the Project page and a Song that’s been added to the Project page, make tweaks to the Song, then migrate the updated Song back to the Project page. But it’s even better when you can make the most important changes earlier in the process, before you start down the final road of mastering.

Here’s a way to match bass and vocal levels in a collection of songs. This takes advantage of the Project page, but isn’t part of the mastering process itself. Instead, you’ll deploy this technique when the mix is in good shape—it has all the needed processing, automation, etc.—but you want a reality check before you begin mastering.

We’ll cover how to match vocal levels for the songs; bass works similarly, and in some ways, more effectively. Don’t worry, I’m not advocating robo-mixing. A mathematically correct level is not the same thing as an artistically correct level. So, you may still need to change levels later in the process—but this technique lets the voice and bass start from a “level” playing field. If you then need to go back and tweak a mix, you can keep the voice and bass where they are, and work the mix around them.

(Note that it’s important to know what the LUFS and LRA metering in the Project page represent. Rather than make this tip longer, for a complete explanation of LUFS and LRA, please check out this article I wrote for inSync magazine.)

- Create a test folder, and copy all your album’s Songs into it. Because this tip is about a diagnostic technique, you don’t want to overwrite your work-in-progress songs.

- Create a new test Project.

- Open a copied Song, remove any master bus processing, and Choose Add to Project for the test project. Add all the other songs on the album to the test project. Do not normalize the songs within the test project.

- Open the Loudness Information section for each song, and select the Post FX tab. Adjust each song’s individual level fader (not the master fader) so all songs have the same LUFS reading, then save the Project. The absolute LUFS value doesn’t matter; choose a target, like -20 LUFS. (When adjusting levels, 1 dB of level change alters the LUFS reading by 1. For example, if a song registers at -18.4 dB, decrease the level by 1.6 dB to reach -20 LUFS. Check and re-check by clicking on Update Loudness as needed until the LUFS readings are the same.)

- Choose a Song to edit (click on the wrench next to the song title). When the Song opens, solo only the vocal track. Then choose Song > Update Mastering File. Note: If a dialog box says the mastering file is already up to date, just change a fader on one of the non-soloed tracks, and try again. After updating, choose View > Projects to return to the test project.

- Repeat step 5 for each of the remaining Songs.

- Select all the tracks in the Project page, then click on Update Loudness.

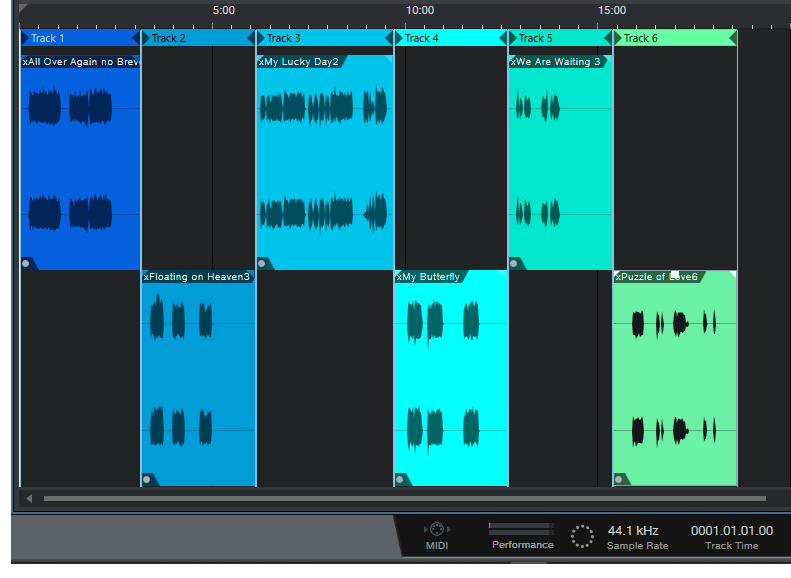

- Check the Loudness Information for each song, which now consists of only the vocal (Fig. 1). For example, suppose the readings for six songs are (1) -24.7, (2) -23.8, (3) -24.5, (4) -22.7, (5) -23.1, and (6) -24.3. Those are all pretty close; we’ll consider -24.5 an average reading. The vocals on songs (1), (3), and (6) have consistent levels. (2) and (5) are a tad high, but song (4) is quite a bit higher. This doesn’t mean there’s a problem, but when you go back to using the original (not the copied) Songs and Project, try lowering the vocal on that song by 1 or 2 dB, and decide whether it fits in better with the other songs.

Figure 1: The songs in an album have had only their vocal tracks bounced over to the Project page, so they can be analyzed by the Project page’s analytics.

The waveforms won’t provide any kind of visual confirmation, because you adjusted the levels to make sure the songs themselves had a consistent LUFS reading. For example, if you had to attenuate one of the songs by quite a bit, visually the vocal might seem louder but remember, it’s being attenuated because it was part of a song that was louder.

Also try this technique with bass. Bass will naturally vary from song to song, but again, you may see a lager-than-expected difference, and it may be worth finding out why. In my most recent album, all the bass parts were played with keyboard bass and generated pretty much the same level, so it was easy to use this technique to match the bass levels in all the songs. Drums are a little dicier because they vary more anyway, but if the drum parts are generally similar from song to song, give it a try.

…But There’s More to the Story than LUFS

LRA is another important reading, because it indicates dynamic range—and this is where it gets really educational. After analyzing vocals on an album, I noticed that some of them had a wider dynamic range than others, which influences how loudness is perceived. So, you need to take both LUFS and LRA readings into account when looking for consistency.

For my projects, I collect all the songs I’ve worked on during a year, and release the completed project toward the end of the year. So it’s not too surprising that something mixed in February is going to sound different compared to something mixed in November, and doing something as simple as going back to song and taking a little compression off a vocal (or adding some in) is sometimes all that’s needed for a more consistent sound.

But let me emphasize this isn’t about looking for rules, but looking for clues. Your ears will be the final arbiter, because the context for a part within a song matters. If a level sounds right, it is right. It doesn’t matter what numbers say, because numbers can’t make subjective judgments.

However, don’t minimize the value of this technique, either. The reason I stumbled on it was because one particular song in my next album never seemed quite “right,” and I couldn’t figure out why. After checking it with this technique, the vocal was low compared to the other songs, so the overall mix was lower as well. Even though I could use dynamics processing to make the song reach the same LUFS reading as the other songs, this affected the dynamics within the song itself. After going back into the song, raising the vocal level, and re-focusing the mix around it, everything fell into place.

How to Use FX Chain Transition Curves

FX Chains are a powerful Studio One feature, yet I can’t help but notice that when I write tips about FX Chains, some people are lost without a download…so I get the impression people might think that making FX chains is difficult. But it isn’t really, and your reward for creating one is a multi-effects processor that you can call up whenever you want, as well as assign controls that allow tweaking parameters without having to open up the effect GUIs themselves.

One of the most important aspects of mapping parameters to knobs is choosing the right Transition settings, so let’s delve deeper into how to make them do your bidding.

Transition Settings Explained

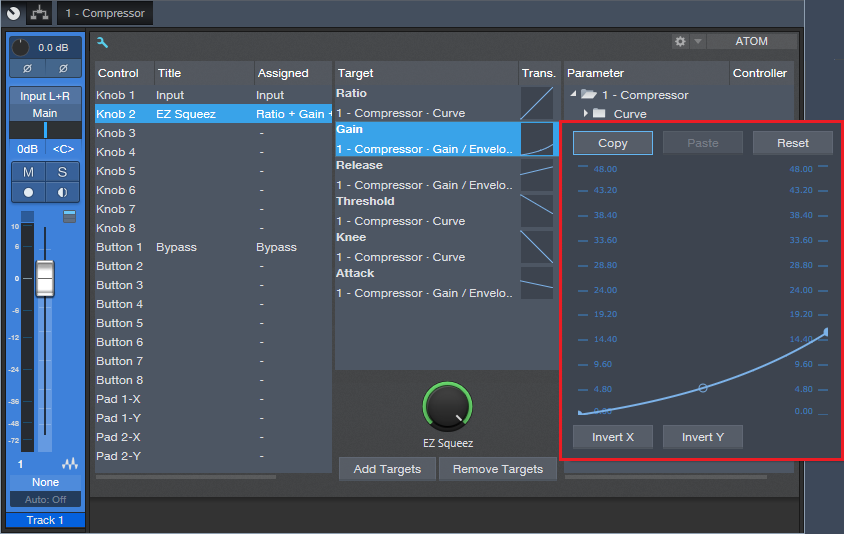

A great aspect of FX Chains is being able to map Macro knobs to multiple parameters and control them all simultaneously. For example, in the EZ Squeez tip for a one-knob compressor, a single Macro knob varied the Compressor Ratio, Release, Threshold, Knee, Attack, and Gain controls simultaneously. Because of this, when changes in the Ratio or Threshold parameter reduced the output, the Gain control could increase automatically to compensate.

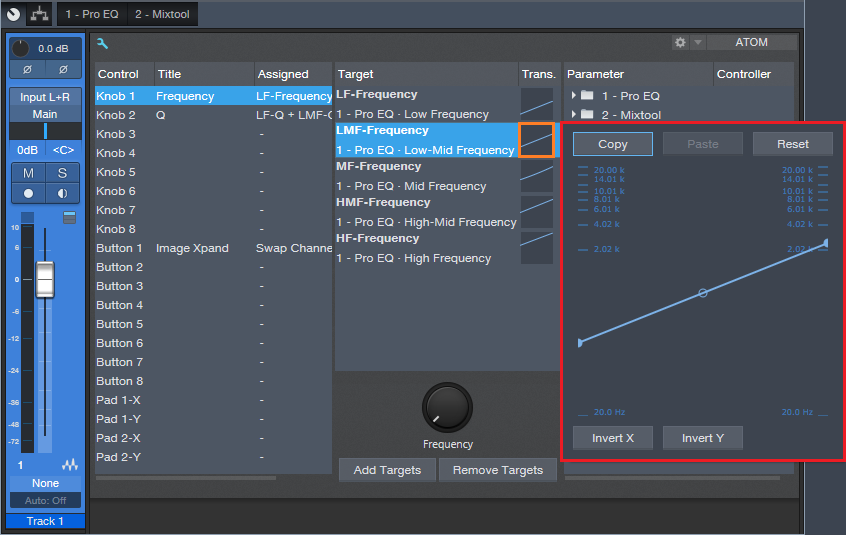

When you map a parameter to a Macro knob, the default is for the knob to alter the parameter over its full range. But, you often don’t want to vary the parameter over its full range. For example, if you were creating a wah pedal effect with the Pro EQ, you wouldn’t want the filter to go from 20 Hz to 20 kHz. A more realistic range would be around 300 Hz to 2 kHz.

The Transition setting allows restricting the parameter range covered by a control. When you click on the small Transition graphic, a bigger view opens up where you can set the parameter’s upper and lower limits (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Click on the small graphic window (outlined in orange) to open up a bigger view (outlined in red).

However, the calibrations are sometimes difficult to read, so it can be challenging to create a precise change. Fortunately, there’s an easy solution.

Suppose you want to change the Pro EQ LMF frequency from exactly 150 Hz to 2.4 kHz (five octave range) by turning one of the Macro knobs. To do this:

- Open the Pro EQ GUI so you can see the LMF Freq knob, and “pin” the Pro EQ so that it remains visible.

- Click on the Knob icon in the Pro EQ’s upper left. The Macro Controls panel will appear (or the Macro Control Mappings window if it was opened up last). Since we want to use the Macro Control Mappings window, if the Macro Controls panel appears, click on its little wrench icon toward the upper left.

- Turn the knob at the bottom of the Macro Controls Mapping window fully counter-clockwise.

- Open the larger transition window for the LMF – Frequency parameter.

- Click on the transition line’s left node, and drag it while observing the LMF Freq knob in the Pro EQ. Stop dragging when it hits 150 Hz; you’ve now adjusted the knob’s lower limit. Note that it’s sometimes difficult to obtain a precise setting; you can’t, for example, type in direct value. You may want to temporarily slow down your mouse pointer speed (in the mouse section of your system properties) to make this easier.

- Now we need to set the upper-frequency limit. Turn the knob at the bottom of the Macro Controls Mapping window fully clockwise.

- Re-open the larger transition window for the LMF – Frequency parameter.

- Click on the transition line’s right node, and drag it while observing the LMF Freq knob in the Pro EQ. This time, stop dragging when the knob’s frequency readout shows 2.4 kHz. Note that you won’t be able to reach exactly 2.4 kHz; the closest I could come was 2.38 kHz…close enough. It’s not always possible to hit a value exactly, but most of the time, this doesn’t matter.

This kind of precision came in handy when creating the Imaging Phaser, where I wanted each frequency band in the Pro EQ to cover five octaves, and the bands had to be offset an octave from each other.

Bend Me, Shape Me

The Transition setting has another very useful feature—you can click the node in the middle to bend the curve into different shapes. For example, the Gain parameter in the EZ Squeez compressor needed to increase in level as the settings became more extreme, which squashed the signal more and brought down the level. Dragging the midpoint down a bit accelerated the amount of Gain as the single knob was turned higher (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Bending the Transition line alters the “feel” of controls.

Where the Heck Are FX Chains Stored, Anyway?

Whenever a FX Chain tip provides a download link, there’s an inevitable comment in the Comments section along the lines of “Where do I store this after I download it”? The easiest way to find out is to go to the Browser, expand the FX Chains folder, expand a sub-folder if necessary, right-click on an FX Chain, and choose Show in Explorer (Windows) or Show in Finder (Mac). Now you’ll know where your FX Chains live. Note that you can also specify the location for your presets in Studio One > Options > Locations > User Data.

Sound Design? “Commitment” Recording? Say What?

Maybe it’s not a well-known feature, but Studio One allows inserting effects or FX Chains before a track, not just in a track. Open up the Input section, and you’ll see a place to insert effects. The only significant limitation compared to inserting an effect in a track is that Input section effects can’t expose their sidechain inputs.

This feature has multiple uses, but first, let’s touch on how it allows for “commitment” recording. Consider recording electric guitar. In the days before tape recorders had enough tracks to do re-amping, you had to commit to recording the final sound on a track. If you decided you should have used a different amp, you had to re-record the part because the track already had that amp sound, and it was unchangeable.

Amp sims (and re-amping) changed all that. You could record a dry guitar track and change the sound at any time, even up to the final mix. While that certainly offers possibilities, it can also cause “analysis paralysis” because some folks can’t just leave a track alone—so they tweak constantly in the hopes of finding something “better.” I’ve spoken with quite a few musicians who are nostalgic for the days when you had to commit to a part because not being tempted by endless tweaking accelerated the songwriting or recording process. Ultimately, some of them felt that the benefits of spontaneity outweighed the benefits of flexibility.

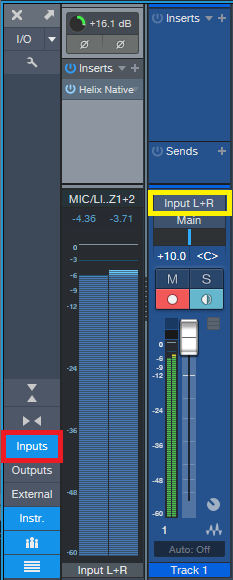

It’s easy to do commitment recording with your amp sim: put the amp sim in Studio One’s input section, not the track. You can also use the Input section’s Input Controls to adjust the gain and phase going in. Record-enable the track, and you’ll record the processed guitar sound into the track (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Click on Inputs (outlined in red) to see the input sections prior to the tracks. In this example, a Helix Native amp sim has been inserted into the L+R input. Track 1 is set to record from Input L+R (outlined in yellow), so it will record the processed sound.

This has other uses, like inserting the Virtual Pop Filter into the input section when recording vocal tracks. Of course, you can always insert the virtual pop filter in the track itself after recording, and render the changes. But it can save time and effort to nuke those stoopid pops before they’re recorded.

RE-AMPING MEETS TRACK-TO-TRACK RECORDING

Some amp sims use a lot of CPU, which can be problematic with projects that include tons of tracks. Of course, with Studio One you can always bounce or transform a track, which saves CPU—and you even have the option to revert and re-edit. However, an alternative technique, track-to-track (TTT) recording, allows one track to record the output of another track. For example, in Fig. 2 the guitar is going through AMR/Peavey’s ReValver amp sim in track 1, while track 2 is recording the processed output from track 1.

So, after doing your recording, track 2 will have recorded the sound of the guitar going through ReValver, not the dry sound. Meanwhile, track 1 will have recorded the dry sound. You can simply bypass the amp sim in track 1 to save CPU (instead of bouncing or transforming), and listen to the amp sim sound from track 2 instead of the dry sound from track 1.

If you want to experiment with different amp sounds in track 1, you know that you always have the recorded sound in track 2 as a fallback. Or, try a different amp sim, pan tracks 1 and 2 somewhat off-center with respect to each other, and now you’ll have a “stack” with a bigger stereo image.

INSTRUMENT TRACKS WITH TTT RECORDING

Here’s perhaps an even more important application for the TTT approach. Some synths have randomizing functions; you can also wire up a modular synth-like Voltage to do all kinds of randomized and sequenced effects. And of course, it’s possible to apply randomized modulation effects to almost any synth. By recording the instrument track’s output, you can capture the randomization of that moment in a track. If you don’t like the randomized effects, then just try again by re-recording the track.

SOUND DESIGN WITH TTT RECORDING

Sound design is all about creating novel, unusual sounds, and you often want real-time control over these sounds while you create them, especially if you’re using external hardware. This is another use for TTT recording. For example, I create a lot of FX sounds and sweeps for transitions and emphasis. Many of them involve the Tone Generator effect generating white or pink noise, followed by plug-in processing, and sometimes hardware effects inserted via Pipeline.

The workflow is simple: insert the white noise generator and plug-ins in the input section, as described above for commitment recording, and record the results in a track. Or, insert the white noise in a track, and use the TTT recording technique—the results are the same, except that TTT creates two tracks instead of one.

But wait—there’s more! The Tone Generator isn’t the only effect capable of making sounds you can record into a track. Several effects, when properly abused, can generate sounds. The internal noise and artifacts generated by these effects are often very low-level, but you can always add a maxed-out Compressor and a few Mixtools after the effect to boost their outputs. And of course, once you’ve recorded the effect on a track, you can normalize it to bring up the level.

- Flanger. Turn up the resonance, and boost the output level, for a variety of cool sci-fi effects.

- Rotor. Turn all the controls to maximum, and turn the power on and off for strange psycho-acoustic panning FX.

- Redlight Dist. This is the most versatile noise generator in Studio One. Oceans, rain, torrential storms…you got it.

- Tone Generator. We mentioned using this for noise, but super-low and super-high frequencies can have merit for sound design, especially when followed by other effects. I’ve gotten some great engine sounds with this and X-Trem.

- Bitcrusher. Think of this as a white noise generator currently serving multiple life sentences. It’s even nastier if you max out a couple Mixtools afterwards, and overdrive them.

The VoxTool FX Chain

Y’all seem to like FX Chains, so here’s one of my favorites—the VoxTool, a toolchest for bringing out the best in vocals and narration as quickly as possible. You’ll still need to add any desired time-based effects (doublers, reverbs, or whatever), or perhaps some compression, but this will help take care of pops, EQ, peaks/transients, and vibrato during the songwriting process. In fact, this FX Chain may even do the job all the way to the final mix.

You can download the FX Chain from the link at the end of this tip; but let’s cover how the various modules affect the sound, so that (if needed) you can tweak this FX Chain for your particular voice.

1. PRO EQ

This stage uses the Low Cut Filter, set to 48 dB/octave, with the cutoff frequency controlled by the Pop Filter control. Turning up this control attenuates the low frequencies where pops occur. The Steeper button adds a bit more low-frequency attenuation, aimed specifically at subsonics, by enabling the LF stage.

2. LIMITER

Now that the p-pops are reduced, we can add some limiting to tame any vocal peaks or transients. The Limiting control in the Macro Controls panel turns up the Limiter’s input control to increase the amount of gain reduction.

3. PRO EQ

This link in the FX Chain uses four filter stages. Like the first Pro EQ, the Low Cut stage ties to the Pop Filter control for further attenuation of sub-vocal low frequencies, while the Steeper switch enables the LF stage for additional pop filtering. The LMF section provides the VOG effect (what narrators call “Voice of God”). This adds fullness to the bass, like an FM late-night DJ, which can also help restore some low-end depth in the vocal range if removing pops extends a bit into the vocal range. The HMF stage is the engine for the Clarity Gain and Clarity Frequency controls. Increasing Clarity Gain adds intelligibility and articulation to the vocals; vary the Clarity Frequency control to find what works best with your voice.

4. ANALOG DELAY

This provides a vibrato effect, with Vibrato Depth and Vibrato Frequency controls applied to the Analog Delay module. You likely won’t want to leave Vibrato Depth up, but instead, control it with automation, a footpedal, mod wheel, or whatever to add vibrato when needed.

That’s all there is to it! So download the VoxTool FX Chain, and bring your vocals up to speed—fast.