Author Archives: Craig Anderton

Friday Tips: Studio One’s Hybrid Reverb

The previous tip on creating a dual-band reverb generated a fair amount of interest, so let’s do one more reverb-oriented tip before moving on to another topic.

Studio One has three different reverbs—Mixverb, Room Reverb, and OpenAIR—all of which have different attributes and personalities. I particularly like the Room Reverb for its sophisticated early reflections engine, and the OpenAIR’s wide selection of decay impulses (as well as the ability to load custom impulses I’ve made).

Until now, it never occurred to me how easy it is to create a “hybrid” reverb with the best of both worlds: using the Room Reverb solely as an early reflections engine, and the OpenAIR solely for the reverb decay. To review, reverb is a continuum—it starts with silence during the pre-delay phase when the sound first travels to hit a room’s surfaces, then morphs into early reflections as these sounds bounce around and create echoes, and finally, transforms into the reverb decay—the most complex component. Each one of these components affects the sound differently. In Studio One, these components don’t all have to be from the same reverb.

THE EARLY REFLECTIONS ENGINE

Start by inserting the Room Reverb into an FX Channel, and calling up the Default preset. Then set the Reverb Mix to 0.00 and the Dry/Wet Mix to 100%. The early reflections appear as discrete vertical lines. They’re outlined in red in the screen shot below.

If you haven’t experimented with using the Room Reverb as a reflections engine, before proceeding now would be a good time to use the following evaluation procedure and familiarize yourself with its talents.

- From the Browser, load the loop Crowish Acoustic Chorus 1.wav (Loops > Rock > Drums > Acoustic) into a stereo track. This loop is excellent for showcasing the effects of early reflections.

- Create a pre-fader send from this track to the FX Channel with the Room Reverb, and bring the drum channel fader all the way down for now so you hear only the effects of the Room Reverb.

- Let’s look at the Room parameters. Vary the Size parameter. The bigger the room, the further away the reflections, and the quieter they are.

- Set the Size to around 3.00. Vary Height. Note how at maximum height, the sound is more open; at minimum height, the sound is more constricted. Leave Height around 1.00.

- Now vary Width. With narrower widths, you can really hear that the early reflections are discrete echoes. As you increase width, the reflections blend together more. Leave Width around 2.00.

- The Geometry controls might as well be called the “stand here” controls. Turning up Distance moves you further away from the sound source. Asy varies your position in the left-right direction within the room.

- Plane is a fairly subtle effect. To hear what it does, repeat steps 3 and 4, and then set Size to around 3.00, Dist to 0.10, and Asy to 1.00. Plane spreads the sounds a bit more apart at the maximum setting.

Now that you know how to set up different early reflections sounds, let’s create the other half of our hybrid reverb.

THE REVERB DECAY

To provide the reverb decay, insert the OpenAIR reverb after the Room Reverb. Whenever you call up a new OpenAIR preset, do the following.

- Set ER/LR to 1.00.

- Set Predelay to minimum (-150.00 ms).

- Initially set Envelope Fade-in and Envelope ER/LR-Xover to 0.00 ms.

There are two ways to make a space for the early reflections so that they occur before the reverb tail: set an Envelope Fade-in time, an Envelope ER/LR-Xover time, or both. Because the ER/LR control is set to 1.00 there are no early reflections in the Open AIR preset, so if you set the ER/LR-Xover time to (for example) 25 ms, that basically acts like a 25 ms pre-delay for the reverb decay. This opens up a space for you to hear the early reflections before the reverb decay kicks in. If you prefer a smoother transition into the decay, increase the Envelope Fade-in time, or combine it with some ER/LR-Xover time to create a pre-delay along with a fade-in.

The OpenAIR Mix control sets the balance of the early reflections contributed by the Room Reverb and the longer decay tail contributed by the OpenAIR reverb. Choose 0% for reflections only, 100% for decay only.

…AND BEYOND

There are other advantages of the hybrid reverb approach. In the OpenAIR, you can include its early reflections to supplement the ones contributed by the Room Reverb. When you call up a new preset, instead of setting the ER/LR, Predelay, Envelope Fade-In, and Envelope ER/LR-Xover to the defaults mentioned above, bypass the Room Reverb and set the Open AIR’s early reflections as desired. Then, enable the Room Reverb to add its early reflections, and tweak as necessary.

It does take a little effort to edit your sound to perfection, so save it as an FX Chain and you’ll have it any time you want it.

Better Reverb with Frequency Splitting

It’s convenient that Studio One has three significantly different reverbs, but none of them has separate decay times for high and low frequencies. This is one of my favorite reverb features, because (for example) you can have a tight kick ambiance, but let the hats and cymbals fade out in a diaphanous haze…or have a huge kick that sounds like it was recorded in a gothic castle, with tight snare and cymbals on top. Also with highly percussive drums, sometimes I’d like a little more diffusion than what’s available so that reflections aren’t perceived as discrete echoes, but rather, as a smooth wash of sound.

So let’s build the ideal Room Reverb for drums (other instruments, too). There’s a downloadable FX Chain that provides a big drum sound template, but note that the preset control settings cover only one sound out of a cornucopia of possible effects. Once you start modifying the reverb sounds themselves, as well as some of the parameters in the Routing window itself, anything’s possible.

ROUTING AND MACRO CONTROLS

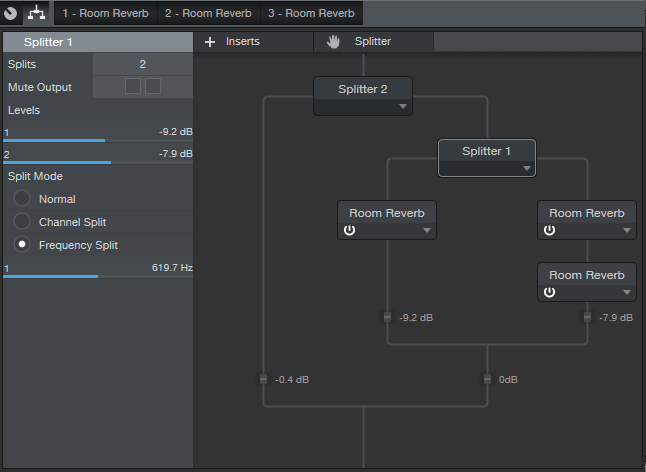

Here’s the FX Chain routing.

Splitter 2 provides a Normal split. One split handles the dry signal, while the other goes to the reverbs. Splitter 1 does a Frequency split, with one split going to a single Room Reverb dedicated to the low frequencies, and the other split going to two Room Reverbs in series for the high frequencies. The Split point (crossover frequency) is set around 620 Hz, but varying this parameter provides a wide variety of sounds.

You might wonder “why not just feed two reverbs, and EQ their output?” EQing before going into the reverb gives each reverb more clarity, because the low and high frequencies don’t interact with each other in the process of being reverberated.

The three Mixtool modules provide mixing for the dry, low reverb, and high reverb sounds, as represented by the first three Macro controls. The other controls modify reverb parameters, but of course, these are only some of the editable parameters available for adjustment within the Room Reverb.

HOW TO USE IT

Here’s one option, although I don’t claim that it’s necessarily “best practices” (suggestions are welcome in the Comments section!).

Start with the Dry, Low Verb, and High Verb controls at minimum. Bring up the Low Verb, and adjust Low Verb Balance and Low Decay for desired low end. Then turn down Low Verb, bring up High Verb, and adjust its associated controls (Hi Verb Balance, Hi Verb Decay, and Hi Verb Damping). With both Low Verb and High Verb set more or less the same, go into the Routing section and vary Splitter 1’s crossover frequency (the slider below Frequency Split). After finding the optimum crossover point, re-tweak the mix if necessary.

Finally, choose a balance of all three levels, and you’re good to go.

WHAT ABOUT THE REVERBS THEMSELVES?

For the default FX Chain preset, the Low Verb has a shorter delay than the High Verbs, but still gives a big kick sound.

The reason for using two Room Reverbs in series for the high reverb component is to increase the amount of diffusion, and provide a smoother sound.

You want fairly different settings for the two reverbs so that they blend, thus giving the feel of more diffusion. There’s not really a lot of thought behind the above settings; I just copied one of the reverbs and changed a few parameters until the sound was smooth.

Incidentally, three Room Reverbs requires a decent amount of CPU, so there are switches at the bottom of the Macro Controls to enable the “eco” mode for each reverb. Choosing eco for the low frequency reverb impacts the sound less than choosing eco for the two high frequency reverbs.

IT’S A WRAP

Download the FX Chain and check out what this FX Chain can do—I think you’ll find that when it comes to reverbs, third time’s a charm.

Click here to get the FX Chain preset!

Friday Tip: Better Vocals with Phrase-by-Phrase Normalization

Unless you have exceptional vocal control, some vocal or narration phrases will likely be softer than others—not intentionally due to natural dynamics, but as a result of sketchy mic technique, running out of breath, or not being able to hit a note as strongly as other notes. Using compression or limiting to even out a vocal’s peaks has its place, but the low-level sections might not be brought up enough, whereas the high-level ones may sound “squashed.”

A more natural-sounding solution is to edit the vocal to a consistent level first, before applying any compression or limiting, by using phrase-by-phrase gain changes that even out variations. The advantage of adjusting each phrase’s level for consistency is that you haven’t added any of the artifacts associated with compression, or interfered with a phrase’s inherent dynamics. Furthermore if you do add compression or limiting while mixing, you won’t need to use as much as you normally would to obtain the same perceived volume and intimacy. A side benefit of phrase-by-phase normalization is that you can define an event that starts just after an inhale, so the inhale isn’t brought up with the rest of the phrase.

Ready to tweak that vocal to perfection? Let’s go.

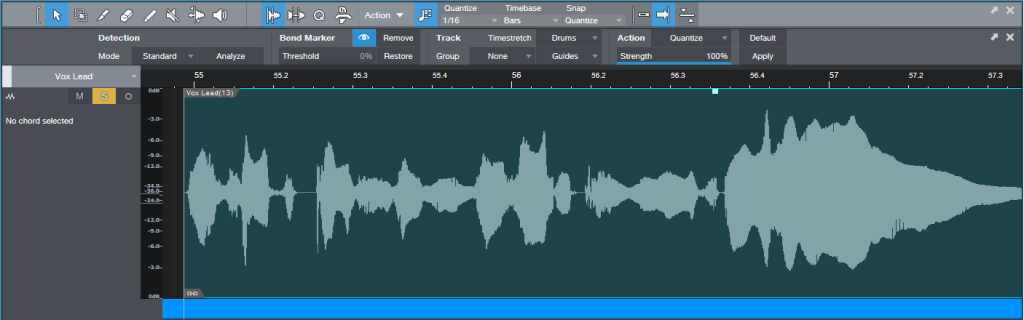

- Open the vocal event in the Edit view, and open the Audio Bend view.

- Click on the Event, and choose Action > Detect Transients. Then click on Remove Bend Markers to start with a clean slate. Your event will look like the above screen shot. (Note: If the vocals have phrases that are separated by spaces, you can choose Transient Detection, Standard Mode, and then click on Analyze. Lower the threshold so that the Bend Markers fall only at the beginning of phrases. However, you’ll may need to move, delete, or add some markers with complex parts, which is why I find it easier just to place Bend Markers where needed.)

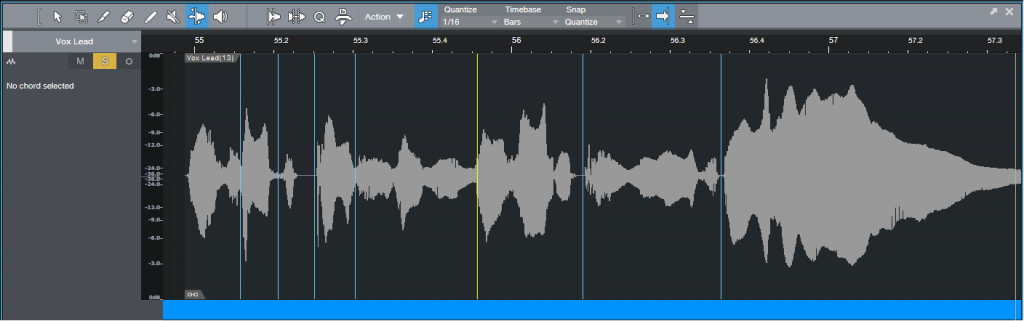

- You can now close the Audio Bend view if you want more room for the waveform height. Choose the Bend tool, and click at the beginning of each phrase to add a Bend Marker. If a section that needs to be adjusted starts in the middle of a phrase, you can add a Bend Marker before the section that needs tweaking anyway, even if there isn’t silence (we’ll explain why later).

- Once you’ve separated the phrases with Bend Markers, select the event in the Edit view by clicking on it with the Arrow tool. Then, choose Action > Split at Bend Markers. Now each phrase is its own event.

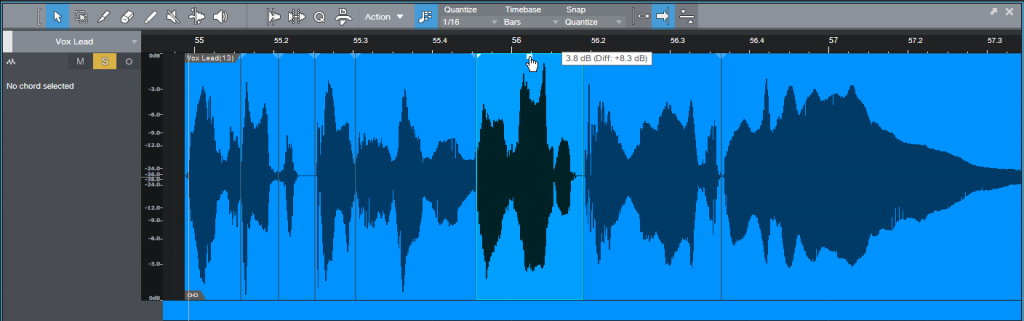

- Click on an event, and then adjust the gain so the event reaches the desired level. Do this with each event that needs tweaking—done!

Note that if audio continues before and after the Bend Marker so the Bend Marker can’t land on silence, Studio One generally handles this well if you place the Bend Marker on a zero-crossing. But if an abrupt level change causes a click at a transition, simply crossfade over it by dragging the end of one event and the beginning of the next event over the transition, and type X to create a crossfade. Adjust the curve for the most natural sound. In extreme cases, fading out just before the click and fading in just after the click can solve any issues.

So why not just do this kind of operation in the Arrange View? Several reasons. First of all, the Edit view is a more comfortable editing environment. But also, sometimes detecting transients will place the Bend Markers accurately enough that all you need to do is split and change levels—it’s much easier than doing a series of splits in the Arrange view. And if you count keystrokes, clicking to drop Bend Markers that define where to split and doing all the splits at once is easier than clicking and splitting at each split. Finally, while in Edit view, you can take advantage of the Bend Markers to adjust phrasing.

While this is a highly effective technique (especially for narration), be careful not to get so involved in this process that you start normalizing, say, individual words. Within any given phrase there will be some dynamics that you’ll want to retain—never lose the human element.

Friday Tips: Studio One’s Zero-Latency/Zero-Artifact Transient Shaper

Studio One doesn’t have a transient shaper plug-in…in theory. In practice, there’s a zero-latency, artifact-free transient shaper that’s ideal for emphasizing the attack in drum parts (and other percussive sounds as well, from bass to funky rhythm guitar). Here’s how to do it.

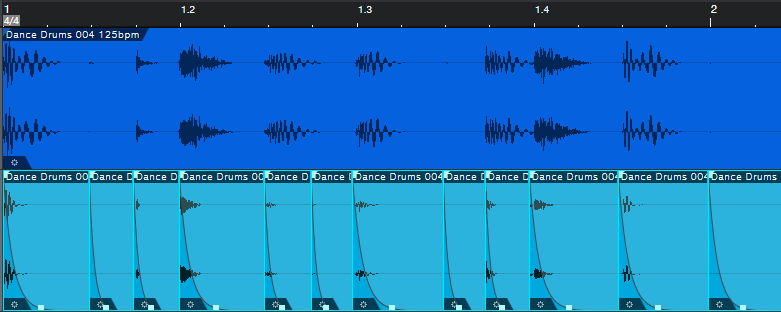

- Copy the clip to which you want to add transient shaping.

- Right-click in the copy, and choose Detect Transients.

- Right-click in the copy again, and choose Split at Bend Markers. The copy now has slices at each transient.

- With all the slices still selected, click on any slice’s fadeout handle, and drag it all the way to the left so that each slice has a sharp decay. Tip: De-select one slice before doing this, because once you drag all the fadeouts to minimum, it’s very difficult to change them. By de-selecting a slice, you can select all the slices, and use the de-selected slice’s fadeout handle to change all the slice fadeouts at once, regardless of the other slices’ settings.

- Click the node in the middle of the fadeout curve, and drag the node down to make all the slices even more percussive.

The top waveform is the original drum part, while the lower waveform adds a sharp decay to each drum transient.

The copy now has the transients isolated from the rest of the loop. Vary the mix of the copied track and the original track to set the balance of the emphasized attack with the loop’s “body.” (Studio One programmer Arnd Kaiser suggests this process might be a good candidate for a macro—that’s an excellent point.)

This technique is particularly effective with acoustic drum loops, because the drums tend to ring longer—so creating a copy as described makes for a super-percussive sound compared to the original loop.

Try this, and you’ll be shocked at how this can make drum parts become more vibrant and “alive.” However, there is one unfortunate side effect: now I wish I could go back and remix all my songs that have drum tracks!

Friday Tips: Keyswitching Made Easy

As the quest for expressive electronic instruments continues, many virtual instruments incorporate keyswitching to provide different articulations. A keyswitch doesn’t play an actual note, but alters what you’re playing in some manner—for example, Presence’s Viola preset dedicates the lowest five white keys (Fig. 1) to articulations like pizzicato, tremolo, and martelé.

Fig. 1: The five lowest white keys, outlined in red, are keyswitches that provide articulation options. A small red bar along the bottom of the key indicates which keyswitch is active.

This is very helpful—as long as you have a keyboard with enough keys. Articulations typically are on the lowest keys, so if you have a 49-key keyboard (or even a 61-note keyboard) and want to play over its full range (or use something like a two-octave keyboard for mobile applications), the only way to add articulations are as overdubs. Since the point of articulations is to allow for spontaneous expressiveness, this isn’t the best solution. An 88-note keyboard is ideal, but it may not fit in your budget, and it also might not fit physically in your studio.

Fortunately, there’s a convenient alternative: a mini-keyboard like the Korg nanoKEY2 or Akai LPK25. These typically have a street price around $60-$70, so they won’t make too big a dent in your wallet. You really don’t care about the feel or action, because all you want is switches.

Regarding setup, just make sure that both your main keyboard and the mini-keyboard are set up under External Devices—this “just works” because the instrument will listen to whatever controllers are sending in data via USB (note that keyboards with 5-pin DIN MIDI connectors require a way to merge the two outputs into a single data stream, or merging capabilities within the MIDI interface you’re using). You’ll need to drop the mini-keyboard down a few octaves to reach the keyswitch range, but aside from that, you’re covered.

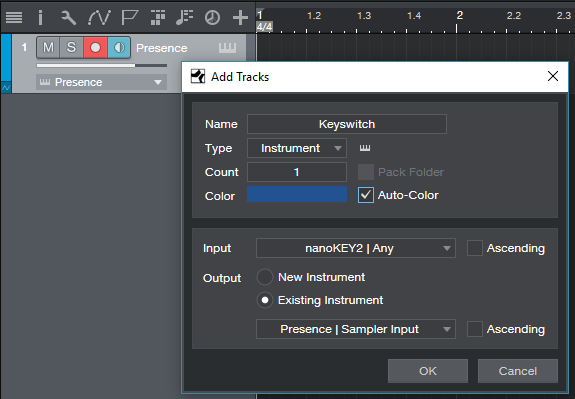

To dedicate a separate track to keyswitching, call up the Add Track menu, specify the desired input, and give it a suitable name (Fig. 2). I find it more convenient not to mix articulation notes in with the musical notes because if I cut, copy, or move a passage of notes, I may accidentally edit an articulation that wasn’t supposed to be edited.

So until you have that 88-note, semi-weighted, hammer-action keyboard you’ve always dreamed about, now you have an easy way take full advantage of Presence’s built-in expressiveness—as well as any other instrument with keyswitching.

Friday Tip—The “Glue” Compressor FX Chain

If you’ve heard people talking about adding “glue” to a mix, this usually involves a bus compressor. But you can also “glue” tracks together in a subtle way by placing two standard compressors in series with high thresholds and low ratios. The result is dynamics control that’s so gentle, you won’t really hear that a compressor is working—but you will hear the benefits.

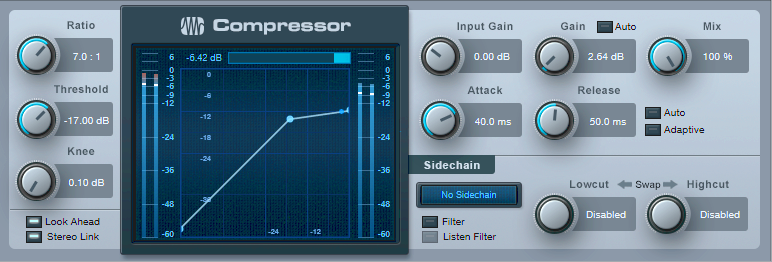

Start by inserting two Compressors in series. I also like adding the Level meter plug-in afterward so it’s easy to compare peak and RMS levels when enabling/bypassing the Glue Compressor. Set the controls that aren’t affected by the FX Chains as follows:

- Compressor 1, Gain 0.00 dB

- Compressor 2, Input Gain 0.00 dB

- Turn off Auto Gain, Auto Release, and Adaptive Release

- Turn on Look Ahead and Stereo Link

Program the FX Chain controls that affect both compressors as follows:

- Ratio: 1:1 to 1.6:1

- Attack: 0.10 to 10 ms

- Knee: 0.10 to 20 dB

- Mix: 0 to 100%

- Release: full range (set to 200 ms default)

Program the remaining controls as follows:

- Input: Compressor 1, full range

- Threshold: Compressor 1 (-20 to 0), Compressor 2 (-6 to 0)

- Gain: Compressor 2, 0 to 6 dB

As to choosing the optimum settings, this one is easy to get wrong. It’s designed for subtle effects, so keep the Input at 0.00 dB unless the incoming signal is very low or high. With an input signal that’s close to maximum, a threshold of -3.0 (as indicated by the Threshold control, because the threshold will differ for the two compressors) and a low ratio (like 1.3:1) are good starting points, with Mix set to 100%.

Adjust Attack (minimum attack clamps down harder on the signal), Knee, and Release based on the input signal characteristics and desired result. Use Gain to match peaks between the bypassed and enabled states. Bypassing and enabling is a good way to hear the difference the Glue Compressor contributes to the sound.

The Glue Compressor is not intended to work like a conventional compressor that flattens an input with a highly variable level, although you can always increase or lower the ratio or threshold for the best sound. Set the controls to give a mild, subtle lift that… well, “glues” the tracks together. You won’t hear a huge difference…and you shouldn’t. But you will hear an improvement that gives the mix a welcome “lift.”

Download the FX Chain preset here.

Friday Tips: Easy Song Level Matching

As you’ve probably figured out, these tips document something I needed, and the solution. If you’ve ever put together an album or collection of songs, you know how difficult it can be to match levels—which I was reminded of all too clearly while preparing the album Joie de Vivre for upload to my YouTube channel. It’s rock-meets-EDM, and is done as a continuous mix that includes not just songs, but transitions. So, all the levels had to be matched very carefully. Fortunately, Studio One’s Project Page made it easy.

The key was using the Project Page’s LUFS meter readings; for a complete explanation of LUFS, please check out the article I wrote for inSync magazine. In a nutshell, it’s a way to measure audio’s perceived level that’s more sophisticated than the usual average, VU, or peak readings. If two songs have the same LUFS reading, they’ll be perceived as having a similar (if not the same) level.

This measurement standard was created in response to issues involved in broadcasting and streaming services, and also in part as a backlash against “the loudness wars.” For example, YouTube doesn’t want you to have to change the level every time a video changes, so they’ve standardized on making all audio -13 LUFS. It doesn’t matter if you squash your master recording until it looks like a sausage, YouTube will adjust the perceived level so that it can slip into a playlist with something like a live acoustic jazz recording.

In Studio One’s Project Page, the Loudness Information section for each song (Fig. 1) shows a song’s LUFS as well as readings for the RMS average level (somewhat like a VU meter) and True Peak, which indicates not just peaks, but whether any peaks are exceeding the maximum headroom on playback, and by how much. The Loudness Information can come from before or after the track’s effects, so to see how editing these alters the LUFS reading, choose the Post FX tab.

Fig. 1: The Tricomp/Limiter combination makes it easy to “fine-tune” the perceived loudness of your songs in the Project Page, as shown by the Loudness Information section (outlined in red).

Leveling the Levels

Now that we know how to measure levels, here’s one way to tweak them for consistency. We’ll assume you want something fairly compressed/limited, but not enough to become collateral damage in the loudness wars.

For each track (likely all of them) that needs to be set to a certain LUFS measurement, insert the Tricomp compressor followed by the Limiter. The screen shot shows my preferred Tricomp settings, but note that the optimum Compress knob setting depends on the material. You don’t want to compress too much, because the limiter will do most of the leveling anyway. If the gain reduction peaks reach the last “s” in “Compress” on the Limiter’s Reduction meter, you probably won’t hear too many artifacts, but you might not want to go any higher.

Next, decide what your target LUFS reading should be. As a very general rule of thumb, most rock songs are around -8 to -10 LUFS. -11 to -14 LUFS is considered as having a decent amount of dynamics, while classical music hangs out around -23 LUFS. Of course, this is all subjective—you can choose whatever level sounds “right.”

Now turn up the Limiter’s input control. The Loudness Information label will change to “Update Loudness.” Click on this; Studio One will analyze the track, and show the LUFS reading. (Note: You can force a reading by right-clicking on the song in the track column, and choosing “Detect Loudness.”)

Adjust the limiter Input level, then update the loudness. If the LUFS is below your target, turn up the Input. If the result is higher than the desired LUFS, turn down the Input. It takes a little trial and error, but eventually you’ll hit the target.

With the Tricomp and Limiter, once you get much above -13 LUFS you can “hear” the limiter because it’s stereo. With a phase-linear multiband maximizer like the Waves L3 Multimaximizer, you can push for higher LUFS readings while still sounding reasonably free of artifacts. Still, I wouldn’t want to go much above -10 LUFS—but as always, that’s a subjective call and there are no rules. If you like the way it sounds, that’s what matters.

However, be aware that even slight tweaks can make a difference, especially with the Tricomp. The Tricomp and the Limiter work together, and you can fine-tune the sound by fine-tuning each processor. For example, having Knee up all the way on the Tricomp gives more perceived loudness, and a narrower dynamic range…which may or may not be what you want. Turning on Autospeed also makes a difference.

When you listen to Joie de Vivre, I think you’ll hear that it benefited considerably by being adjusted in Studio One to a consistent LUFS reading. There’s a decent amount of dynamics, but the average perceived level of all the cuts is very consistent…and that’s what this tip all about.

Friday Tips: Humbucker to Single-Coil Conversion with EQ

Humbuckers are known for a big, beefy sound, while single-coil pickups are more about clarity and definition. If you want the best of both worlds, you can warm up a soldering iron, ground the junction of the humbucker’s two coils, and voilà—a single coil pickup. But there’s an easier way: use the Pro EQ, which gives the added benefit of not losing the pickup’s humbucking characteristics.

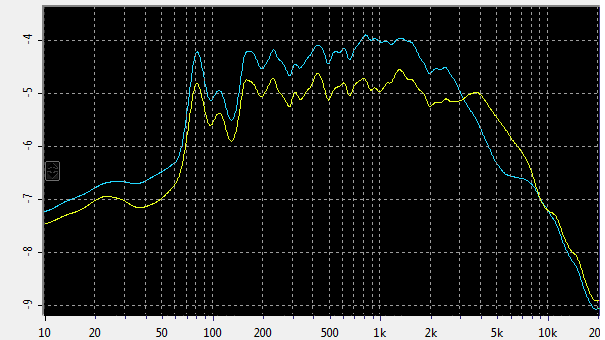

The main difference between humbucker and single coil pickups is the frequency response. The blue line in Fig. 1 shows a humbucker’s spectral response, while the yellow line shows the same humbucker split for single-coil operation. Unlike the single-coil’s response, which is essentially flat from 150 Hz to 3 kHz, the humbucker has a bump in the 500 Hz to 2 kHz range that contributes to the “beefy” sound. Starting at 3 kHz the humbucker response drops off rapidly, while the single coil produces more high-frequencies than the humbucker from 3 kHz to 9 kHz.

Fig. 2 shows an equalizer curve that modifies a bridge humbucker for more of a single-coil response. Of course different humbucker and different single-coil pickups sound different, so this kind of EQ-based “modeling” is an inexact science. However, I think you’ll find that the faux single-coil sound delivers the distinctive, glassy character you want from a single-coil pickup. Feel free to tweak the EQ further—you can come up with variations on the single-coil sound, or “morph” between the humbucker and single-coil characteristics.

The difference between a neck humbucker and single-coil response isn’t as dramatic, but the curve in Fig. 3 replicates the neck single-coil character, and provides yet another useful variation for your guitar tone.

The bottom line is that you don’t need to break out a soldering (or void your guitar’s warranty) to make your humbucker sound more like a single-coil type—all you need is the right kind of EQ.

Friday Studio One Tips: The Guitar Sustainer

This signal processing setup is optimized for single-string guitar solos where you want a lot of sustain—but it has a secret ingredient that puts it ahead of typical guitar stompbox sustainers.

The compression aspect is pretty straightforward. A sustainer is all about a high compression ratio and low threshold, which are set to 20:1 and -35 dB, respectively. The sharp knee keeps the sustain going as long as possible, and a short attack time clamps down the attack. The release time isn’t too critical, although this depends on your playing style; a relatively long one (300-500 ms) usually works best.

This is one of those rare instances where you don’t want to enable the compressor’s Auto or Adaptive feature, because the goal here isn’t the most natural sound—it’s an effect. However, enable Lookahead because it helps to tame the attack.

Because of the extreme amount of compression, you’ll need about 30 dB of makeup gain to compensate for the gain reduction due to compression.

And now, the secret ingredient! With most sustainers, after the release time ends, if there’s a pause between notes you’ll hear a loud “pop” when you play a new note because of the compression kicking back in. A fast attack and lookahead helps, but it’s almost impossible to avoid some kind of nasty transient. If you follow the compressor with an amp sim, the distortion will hide the pop somewhat but it can still lead to an ugly attack.

Enter the noise gate. This doesn’t just remove hum, noise, and other low-level signals from being sustained, but the 55 ms attack time (coupled with the enabled lookahead button) means that when you hit a note after a pause, the note attack ramps up more slowly, so the compressor can “grab” the note without creating a pop (or if it does, the pop will be greatly reduced). If there’s an amp sim involved, you’ll hear a cleaner attack, and better overall sound. Note that depending on how fast you play and the compressor’s release time, you may need to shorten the Noise Gate’s Release and Hold times. In any event, when you want serious ssssssuuuuussssstttttaaaaaiiiiinnnnn for your single-note guitar solos, this is the ticket.

Friday Tips: Studio One’s Transient Shaper for Kick and Snare

As with so many aspects of audio, the subject of compression presets polarizes people. The purists say there’s no point in having presets, because every signal is different, and the same compressor settings will sound very different on different sources. On the other hand, software comes with presets, and there are plenty of recording blogs on the web that dispense advice about typical preset settings. So who’s right?

And as with so many aspects of audio, they all are. If a preset works “out of the box,” that’s just plain luck. However, there are certain ranges of settings that work well in many cases for particular types of signals. In any case, the effects of compression are totally dependent on the input signal level anyway—if the threshold is set to -10, then signals that peak at 0 will sound very different compared to signals that peak at -10.

The most effective way to approach compression is to decide what effect you want the compression to accomplish, then adjust the compression settings accordingly. It’s also important to remember that compression isn’t just some monolithic effect that “squashes things.” For example, with kick and snare, compression can act just like a transient/decay shaper due to a drum’s rapid decay.

The usual goal for compressing kick is an even sound, yet one that doesn’t reduce punch. However, you have a great deal of latitude in deciding how to implement that goal.

The preset in Fig. 1 uses a fairly high ratio, and hard knee, to even out the highest levels. You want the compression to take hold relatively rapidly, but not take away from the punch. The best option is to start with the attack time at 0, and increase it until you hear the initial hit clearly (but don’t go past that point). Because a kick decays fast, release can be fast as well.

For transient shaping, slowing the attack time softens the attack. Raising the ratio increases the sustain somewhat, while making space for the attack (assuming an appropriate attack time). Between the attack and ratio controls, you can pretty much tailor the kick drum’s attack and sustain characteristics, as well as even out the overall sound. A higher threshold is another way to emphasize the attack, by letting the decay occur naturally. Lowering the threshold reduces the level difference between the attack and decay.

Snare responds similarly to kick, however with an acoustic drum kit, the kick is more isolated physically than the snare. As a result, compressing the snare has the potential to emphasize leakage. Fortunately, the snare is often the focus of a drum part. As a result, you can simply compress the snare, and accept that leakage is part of the deal. With individual, multitracked drums (including electronic drums) where leakage is not a problem, it’s still usually the snare and kick that get compression.

With snare, you may want to use a lower ratio (2:1 – 3:1) for a fuller snare sound. Or, increase the ratio to emphasize the attack more. Again, use the attack time to dial in the desired attack characteristics.

With both kick and snare, you’ll usually want a hard knee. However, the knee control is a fantastic way to fine-tune the attack—and once you have that dialed in, you’ll be good to go.