Studio Magic Suite Demo and Tutorials with Richard Gaspard!

Check out the great Studio Magic Suite Demo playlist from Richard Gaspard below. It features six videos that cover each plug-in available for free with the Studio Magic Plug-in Suite, like Klanghelm SDRR2tube, Brainworx Opto, Lexicon MPX-1, Maag EQ2, Output Movement, and SPL Attacker. ALL FREE when you buy a PreSonus interface or mixer… That’s over a $400 value!

Take a look at the whole suite here:

Learn more about the Studio Magic Suite here! It’s FREE and available right now in your My.Presouns account!

Friday Tip: Rotating Speaker Emulator FX Chain

A rotating speaker is an extremely complex signal processor (as most mechanical signal processors are—like plate reverbs). It combines phase shifts, Doppler shifts, positional changes, timbral variations, and more. And of course, Studio One includes the Rotor processor, which does a fine job of capturing the classic rotating speaker sound.

However, I’ve always felt that rotating speakers have a lot more potential as an effect than just emulating physical versions—hence this FX chain. By “deconstructing” the elements that make up the rotating speaker sound, you can customize it not only to tweak the rotating speaker effect to your liking, but to create useful variations that don’t necessarily relate to “the real thing.” What if you want a speed that’s between slow and fast? Or a subtler effect that works well with guitar? Or simulate the way that the horn spins faster when changing speeds because it has less inertia than the woofer? This FX chain provides a useful, more subtle variation on Rotor’s rotating speaker sound—check out the audio example—but the best way to take advantage of this week’s tip is to download the multipreset, roll up your sleeves, and start playing around.

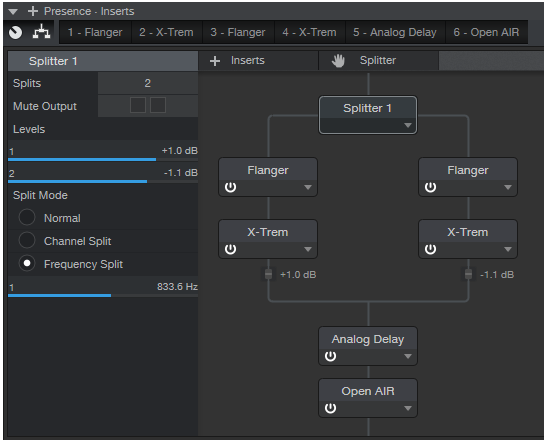

Rotating speaker basics. There are two rotating speakers—one high-frequency driver, and one low-frequency drum. A crossover splits the signal to these two paths, so we’ll start the emulation by setting the Splitter to Frequency Split mode around 800 Hz. Here’s the routing.

The high-frequency and low-frequency paths each go into a Flanger to provide Doppler and phase shifts, and an X-Trem for subtle panning to provide the positional cues. Let’s look at the individual module settings.

The Analog Delay adds a 23 ms reflection for a bit of a room sound vibe, with some modulation to add a Doppler shift accent. Finally, an Open Air reverb (using the 480 Hall from Medium Halls) creates a space for the rotating speaker.

Knob Control. This was the hardest part of the emulation, because changing speed has to alter (of course) Flanger speed, but also the Flanger’s LFO Width because you want less width at faster LFO speeds. The X-Trem speed and Analog Delay LFO speed also need to follow the range from slow to fast.

However, the curves for the control changes are quite challenging because the controls don’t all cover the same range. Fortunately you can “bend” curves in FX Chains, but you can’t have more than one node. As a result, I optimized the knob settings for the lowest and highest speeds—besides, a real rotating speaker switches to either speed, and “glides” between the two settings as it changes from one to the other. An additional subtlety is that the high-frequency “speaker” needs to rotate just a little faster than the low-frequency one. Also, they shouldn’t track each other exactly when going from the slowest to the fastest speed because with a physical rotating speaker, the low-frequency drum has more inertia.

All these curves do complicate editing any automation, because you need to write-enable each parameter when you turn the knob. So if you need to change some automation moves you made, I recommend not trying to edit each curve—just try another performance with the knob.

Oh, and don’t forget to try this on instruments other than organ!

CLICK HERE TO DOWNLOAD!

Listen here:

Friday Tip: Smoother, Gentler Sidechain Gating

I’ve always been fascinated with using one instrument to modulate another—like using a vocoder on guitar or pads, but with drums as the modulator instead of voice. This kind of processing is a natural for dance music, and using a noise gate’s sidechain to gate one instrument with another (e.g., bass gated by kick drum) is a common technique.

However, the sound of gating has always seemed somewhat abrupt to me, regardless of how I tweaked a gate’s attack, decay, threshold, and range parameters. I wanted something that felt a little more natural, a little less electro, and gave more flexibility. The answer is a bit off the wall, but try it—or at least listen to the audio example.

Setup requires copying the track you want to modulate (the middle track below), and then using the Mixtool to flip the copy’s audio 180 degrees out of phase (i.e., enable Invert Phase). This causes the audio from the original track and its copy to cancel. Then, insert a compressor in the copy, and feed its sidechain with a send from the track doing the modulating. In this case, it’s the drum track at the top.

When the compressor kicks in, it reduces the gain of the audio that’s out of phase, thus reducing the amount of cancellation. However, as you’ll hear in the example, the gain changes don’t have the same character as gating.

You can also take this technique further with automation. The screen shot shows automation that’s adjusting the compressor’s threshold; the lower the threshold, the less cancellation. Raising the threshold determines when the “gating” effect occurs. Also, it’s worth experimenting with the Auto and Adaptive modes for Attack and Release, as well as leaving them both turned off and setting their parameters manually.

Using a compressor for “gating” allows for flexibility that eluded me when adjusting a standard noise gate. If you want super-tight rhythmic sync between two instruments, this is an unusual—but useful—alternative to sidechain-based gating.

Friday Tip: Perfect Pads!

Pads that Loop Perfectly—Yes, It’s Possible!

Pads are hard to loop, because their flowing, continuous sound exposes loop points that are anything less than seamless—there will often be a click, pop, or other glitch. But there is a solution, so keep reading for how to create perfect loops for just about any pad.

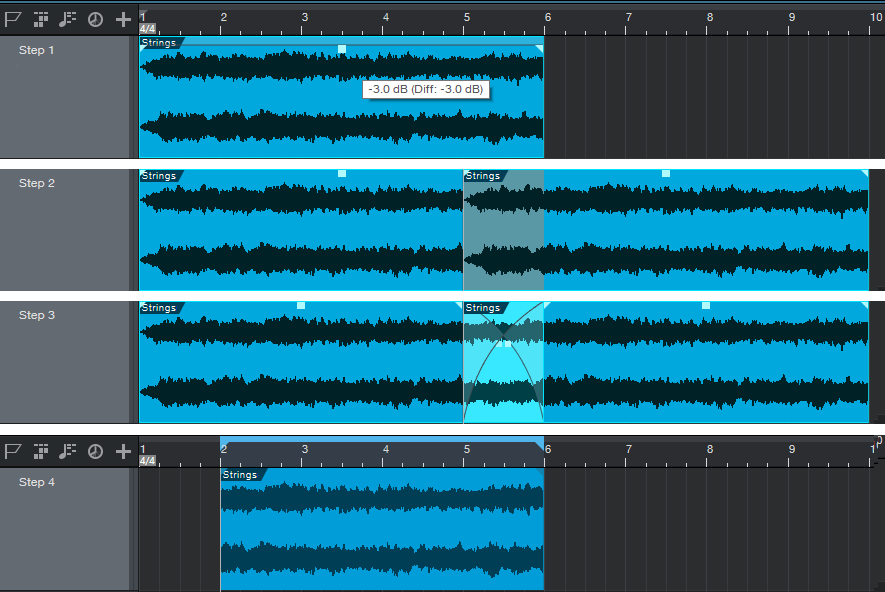

Step 1. Record a pad that’s one measure longer than what you want to loop. For example, record five measures to create a loopable four-measure pad. Normalize, then reduce the level by -3 dB or so to accommodate peaks that may result from later crossfading. Then, bounce the clip to itself to make this level change permanent.

Step 2. Copy the clip, and then paste it (or alt+drag the clip) so the first measure of the copy overlaps the last measure or the original clip. In this example, the overlap extends across measure 5.

Step 3. Shift+click on the original clip and the copied clip so they’re both selected, then type X to create a crossfade. Move the crossfade nodes up to create a logarithmic fade.

Step 4. With both clips still selected, bounce to create a single clip. Split at the end of the first measure and at the end of where the clips overlapped (in this case, measure 6). Delete both ends so what’s left extends from the start of measure 2 to the end of measure 6. Bounce what’s left to itself, loop it, and you’ll hear a perfect 4-bar loop.

Note: In some particularly challenging cases, you may need to overlap the clip’s first two measures over the clip’s last two measures to create a suitable crossfade. However, if the pad is relatively consistent you almost certainly won’t encounter any issues.

Friday Tip: Back to the 60s with Preverb

Reverse audio was a common technique back in the days when doing it was a challenge (flipping tape reels over, recording, flipping them back). Now that reverse audio is easy to do, it’s uncommon…go figure. But let’s revive reverse audio with preverb—reverb that swells up to a sound, instead of decaying after it. We’ll first look at a method that requires having some silence before the clip to which you want to add preverb, then cover what to do if the clip starts at the beginning of a song. Note: the screen shot shows each step, but you’ll end up with only the two yellow clips to create preverb—the other clips are for illustration only (i.e., you don’t need to keep copying the clip).

Step 1. Start by copying the clip or track to which you want to add preverb. Use the Paint tool to draw a silent section in front of the copied clip that’s equal to or longer than the anticipated reverb decay tail you’ll add in the next step, then bounce the silent part and the copied clip together. Tip: Consider rolling off some of the low end on the copy so the kick is less prominent. Kicks don’t get along with reverb all that well, and preverb is no exception.

Step 2. Select the bounced clip and type Ctrl+R, or right-click and choose Audio > Reverse Audio. Insert your reverb of choice (the Open Air 480 Hall preset from Halls > Medium Halls is a good place to start) into the copied/reversed track or clip, then set the reverb’s Mix control to 100% for an all-wet mix.

Step 3. After your reverb sound is as desired, right-click on this clip and choose Mixdown Selection. This clip contains only the reverb sound.

Step 4. Reverse this clip, and now you’ll preverb when you play it along with the original clip. You can also try nudging the preverb left or right to play with the timing—for example if the reverb has pre-delay, the kick and reverberated kick might argue with each other.

To add preverb before the entire song starts so that the preverb leads up to the first sound, select all tracks and shift them to the right to open up a few measures at the song’s beginning. Now you can extend the copy of the track or clip you want preverbed to the project start so it includes silence. Continue by copying the original track, reversing, and following the steps detailed previously to add preverb, then shift the tracks back to the their original position.

To hear preverb in a musical context, go to https://store.cdbaby.com/cd/craiganderton and click on the free preview of song 2, “The Gift of Goodbye.” The preverb is on the guitar solo toward the middle of the song and then occurs again at the end, during the fadeout.

Friday Tip: Reverb Chord Progressions? Why Not!

The more I play with Harmonic Editing, the more I find it can do things I never expected. Check this out…

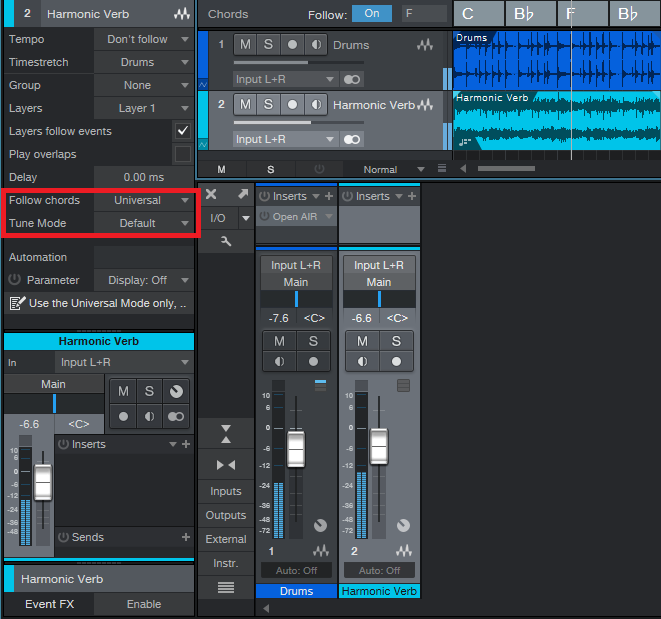

One very useful Studio One feature is being able to record a track output into another track’s input. I take advantage of this sometimes by recording effects like reverb or envelope filter (set to effect sound only) into a track. This allows using Inspector features like transpose and delay, as well as have easier control during the mix.

So imagine my surprise when I set the reverb-only track to follow the Chord Track—and ended up with a tuned reverb chord progression! The following audio example gets the point across. The first four measures have the original reverb sound, the second four measures have the reverb processed by the Chord Track…pretty amazing.

There’s one caution: The only Follow chords mode that works for this is Universal. The Tune Mode doesn’t seem to matter, so I just use Default.

Extra bonus coolness tip! Drums can follow the Chord Track, again in Universal Mode, for a “drumcoded” effect (i.e., similar to drums “vocoding” something like a pad). Although there’s no way to do a wet/dry balance of the melodic and non-melodic components, you can copy the track, have only the copy follow the Chord Track, and adjust the mix between the dry and Chord-Track-following track.

The mind boggles.

Friday Tip: The Secret of Virtual Octave-Divider Bass

Seems simple enough, right? Copy the bass track, edit with Melodyne, and drop all those adorable little orange blobs down an octave. So you do that and… well, it just doesn’t sound all that impressive.

The secret to a great octave-divider bass sound is EQ. Insert a Pro EQ in the track you octave-divided with Melodyne, and edit the settings as shown in the screen shot. The goal is to remove most of the high frequencies that have pick and finger noises—we already have enough in the primary bass track, so adding more artifacts just clutters the sound.

The screen shot shows a High Cut setting of about 600 Hz; you can take it down further, but when the frequency reaches about 200 Hz or so it sounds more like a synth sub-bass (not necessarily a bad thing, especially if you add a little limiting).

And that’s really all there is to it. When you bypass the EQ as a reality test, you’ll hear for yourself why EQ is indeed the secret of virtual octave-divider bass.

Friday Tip: Stereo to Virtual Mono

There are several ways to convert stereo into two mono tracks with Studio One (e.g., for processing the two channels separately, reversing one channel but not the other, etc.), but those ways can be somewhat convoluted. One simple way to convert a stereo track into mono involves going into the Browser, right-clicking on the track’s filename, and selecting Split to Mono Files. But if a track consists of multiple clips from multiple files, then you first need to bounce them to create a track—yet you might not want to bounce them until later. And you’re also creating additional files.

The approach in this tip doesn’t create true mono tracks, but it treats a stereo track as two different tracks that behave exactly like mono tracks—which is probably the desired goal anyway. This method also doesn’t create any additional files, and is non-destructive.

- Insert a Dual Pan into your stereo track. Set Input Balance to Left (fully counter-clockwise), and the Left and Right controls to Center.

- Select the track and choose Duplicate Track (Complete).

- In the duplicated track, set the Dual Pan Input Balance to Right (fully clockwise).

The original track becomes the left channel and the duplicated track, the right channel. Now you can process and pan each channel individually. To avoid confusion, rename one track so it includes the letter L, and the other so it includes the letter R. In the screen shot, the right track is red and the left track is white to follow the color scheme of RCA phono jack stereo connections in consumer electronics devices. Hey, why not?

Friday Tip: Make Mastered Songs Better with Tempo Changes

We covered tempo changes previously, with an emphasis on using tempo changes to add dramatic pauses, and also doing longer changes that are useful with DJ sets when transitioning from one song to another. This week, let’s go one step further.

In the process of researching an article for Sweetwater.com about what made classic rock sound “classic,” I analyzed tempo variations in songs without click tracks. The consistency of these changes was surprising. Although the changes did not have machine-like precision, they were far from being random or sloppy. They tended to follow particular patterns not only in different songs, but different genres.

The most prominent of these was speeding up a bit in the verse before a chorus. Sometimes there would be a slight slowdown after arriving at the chorus, and sometimes it would revert pretty close to the original tempo over the course of the chorus, but the speeding up was evident in virtually all the music I analyzed—rock, pop, R&B, soul, you name it. Also, songs often sped up imperceptibly over the course of a song.

Although you can record while Studio One is doing a tempo change, sometimes it’s a lot easier to play along with a regular click. Fortunately, there’s a way to add these tempo changes after the fact, to the final stereo mix—consider it a mastering technique done in the Song Page, not a tracking or mixing one.

PREPARATION

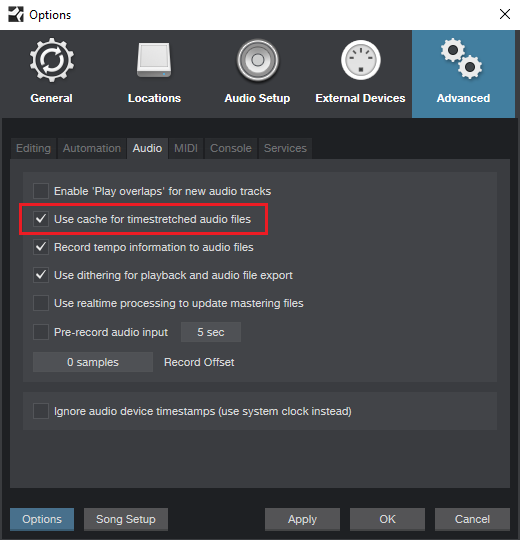

Working on the mixed track requires the highest fidelity possible. Choose Options > Advanced > Audio and check “Use cache for timestretched audio files.”

This uses a higher-quality timestretch algorithm than what’s used for real-time disk playback.

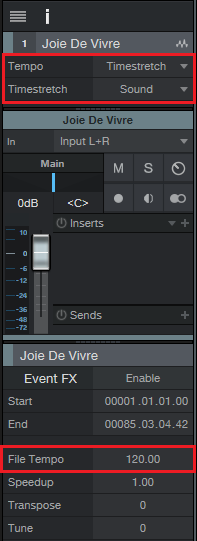

Next, open up a new song and load your mixed file into a track. It won’t have tempo information embedded so Studio One won’t know how to stretch it, but that doesn’t matter. Open the Inspector (F4), and enter a tempo under File Tempo, for example 120 BPM. It doesn’t have to match the original file’s tempo because we’re just introducing changes, not dealing with absolute tempos.

While you’re in the Inspector, choose Tempo = Timestretch, and Timestretch = Sound.

MAKING CHANGES

I generally do a linear speed up, because the changes (e.g., 2-5%) aren’t big enough that you’d notice a log curve anyway. While holding the Alt/Opt key, click with either the Paint or Line tool where you want the tempo to start speeding up, and drag to where you want the speedup to end. Note that you can also drag up or down to fine-tune the end tempo, and if you also hold Shift while doing this, you can change tempo in 0.1 BPM increments.

While the range of tempo changes is still selected, zoom in on the very first change. It will be slightly more than the tempo before it, which is usually what you want. If not, hover over the top of the first tempo change until it turns into a double up/down arrow. Click, and drag downward to even out the first tempo change with the tempo change right before it. The selected changes will follow along to preserve the line’s slope. Remember, we’re talking about small changes here that are more felt than heard as obvious tempo shifts. You can be off by a few tenths of a BPM, or even more—no one will notice.

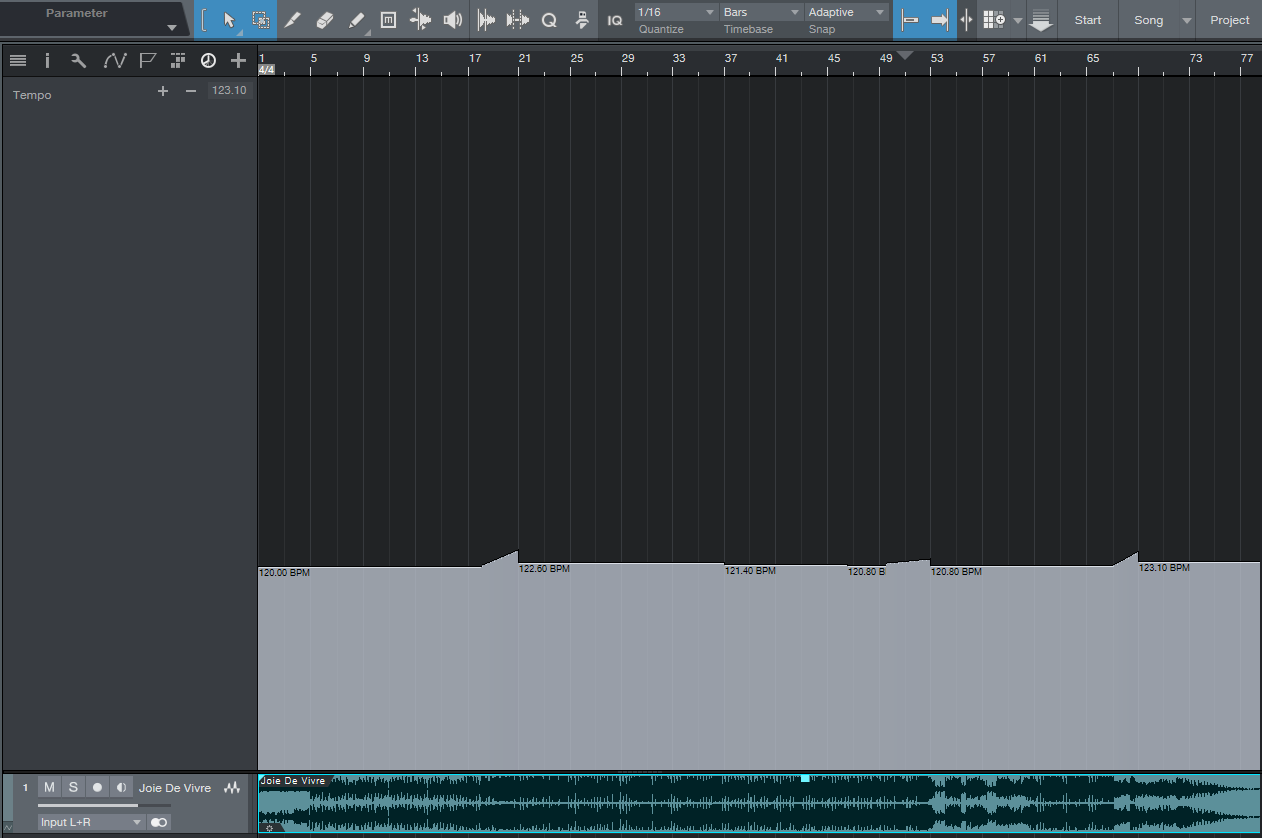

The screen shot shows a mastered song after having tempo changes made. I like to extend the tempo track height as much as possible so it’s easy to make fairly precise changes. Note the linear changes that happen before the two choruses about 1/3 and 2/3 through the song, and then another before the final fadeout on the main riff. In the middle, there’s also a slightly slower tempo change during the solo.

Try this technique on your finished songs—you might be surprised about how these can help a song “breathe” and flow more, even if it was recorded to a click track.

The Latest Banging Add-Ons in the PreSonus Shop!

Get Tom Brechtlein’s Drums HERE!