Category Archives: Studio One

Recording in Studio One Made Easy with David Vignola!

Learn Studio One from David Vignola!

Learn Studio One from David Vignola!

This series is intended for first-time owners of the AudioBox and Studio One Artist and covers everything you will need to know to record your first song. Hit the ground running!

And when you’re ready for the Advanced course, hit up David at his website and get a discount with promo code: PRESONUS25

Watch the whole video series here:

Learn more about the AudioBox here!

Not sure which interface works for you? Well help you find one here!

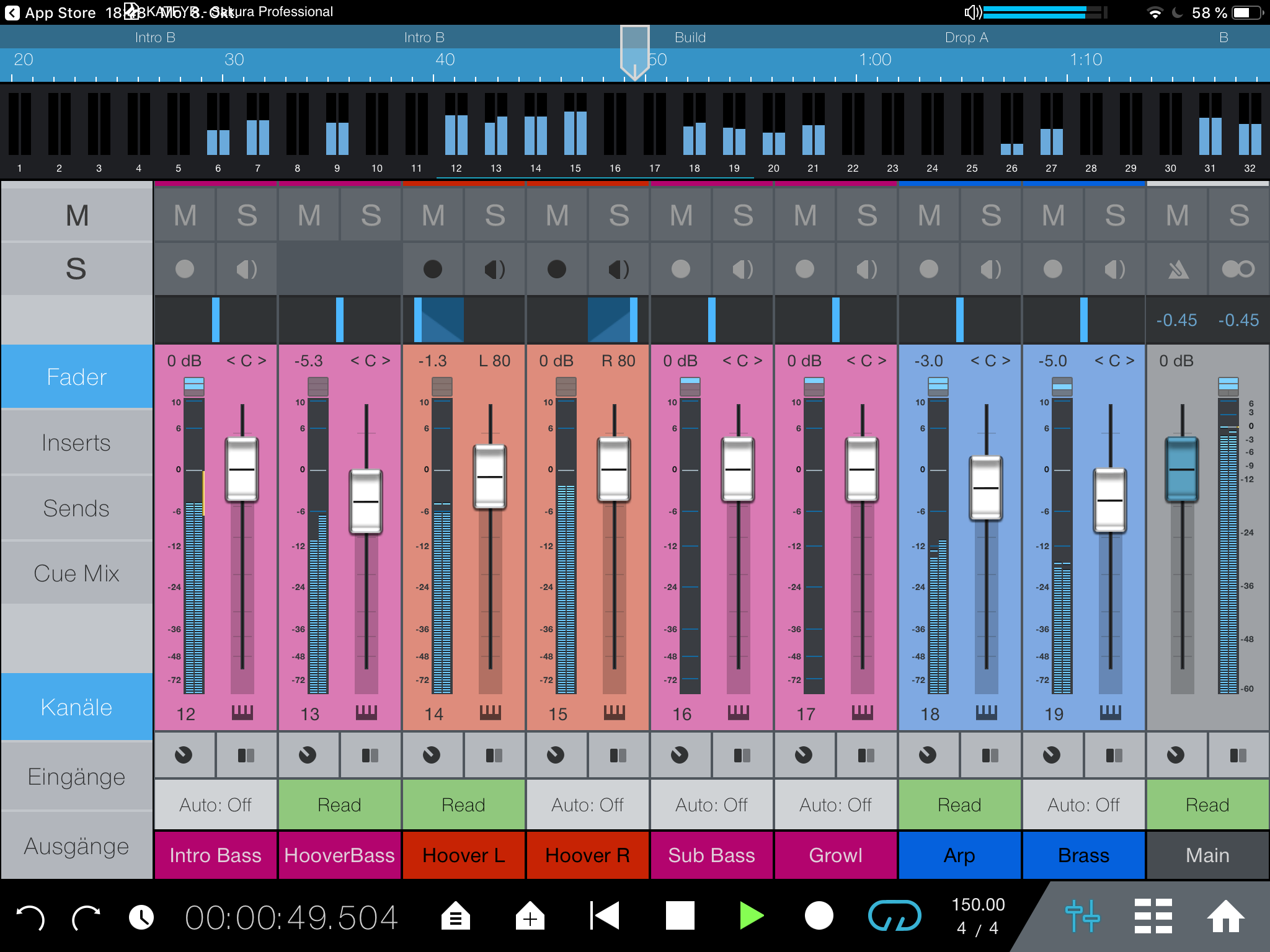

Studio One Remote 1.4 Available Now

New in version 1.4:

- Support for Studio One 4 dark and light UI themes (selectable from the Start Page)

- Updated mixer graphics

- Several bugfixes and performance improvements

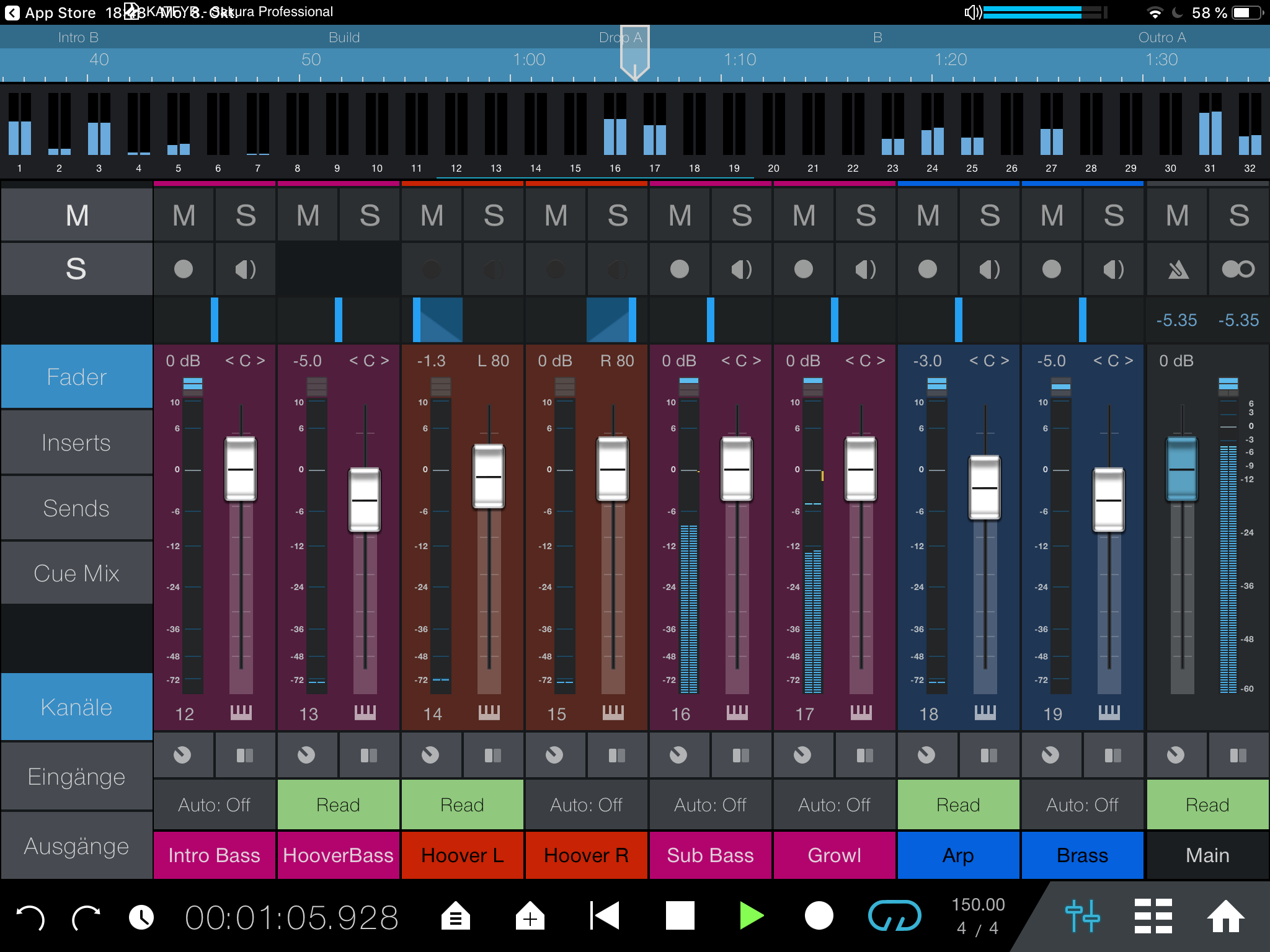

Friday Tips: Pumping Drums—With No Sidechain!

The “pumping” effect is a cool EDM staple that also works with other intense forms of music. One of the best-known examples is Eric Prydz’s seminal EDM track from 2004, “Call on Me.” Usually, this technique requires sidechaining, but with the PreSonus Compressor sidechain filter, we’re covered. The effect works best if there are some sustaining sounds with which it can work—like cymbals for drum parts, or pads if you want to pump a non-drum track. Listen to the audio example to hear how the pumping effect alters a drum track.

To start, let’s try pumping some drums. Insert the Compressor in the track, and click on the Compressor’s Filter and Listen Filter buttons. To have the kick create the signal that provides the pumping, set the Lowcut frequency to off, and lower the Highcut filter until you hear pretty much nothing but kick. Once you’ve isolated the kick (or snare, or whatever you want to isolate), turn off Listen Filter but leave Filter on.

The control settings are quite crucial; the screenshot shows some potential initial settings, but you’ll need to edit the controls based on the source audio and the desired effect.

The effect’s depth, like any compression effect, depends on the Threshold and Ratio settings. For a pretty heavy-duty effect, set Threshold between -20 and -30 dB and Ratio around 10. You’ll want to tweak this depending on the program material, but it’s a good place to start.

Now for the pumping. Start with Attack at minimum, and set Release for the desired amount of pumping—you’ll probably want a time between 100 and 300 ms, depending on the song and the material. To restore some of the attack at the start of the pumping, increase the Attack time. Even a little bit, like 5 ms, restores most of the attack’s effect.

Finally, note that because this effect does in fact compress, you’ll probably want to add some makeup gain. And once you do, there you have it—the pumping sound.

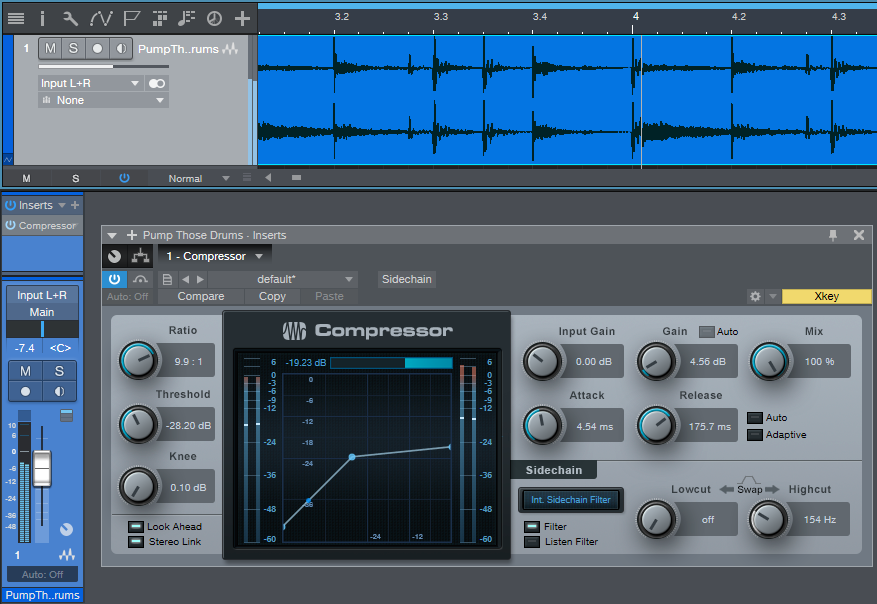

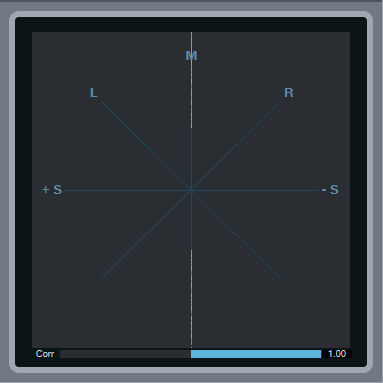

Friday Tips: What’s a Phase Meter—And Why Should I Care?

I’ve always appreciated Studio One’s analytics—the spectrum analyzer, the dynamic range meter in older versions and the more modern LUFS metering in Studio One 4, the K-Scale meters based on Bob Katz’s research, the strobe tuner, and the ability to stretch the faders in the Mix view when you want to couple high resolution with long fader travel. But I wonder if the Phase Meter and its companion Correlation Meter get the props they deserve, so let’s look at what this combo can do for you.

Phase Meters—Not Just for Mixdowns!

Most people consider a tool like the Phase Meter as being only for checking final mixes. However, one very useful technique is putting it in the master output bus, and soloing one track at a time (remember, you can Alt+click on a track’s Solo button for an “exclusive solo” function). This gives some insights into the phase, level, and stereo spread of individual tracks in a way that’s more revealing than just looking over panpots.

Correlation Meter Basics

In brief, the Correlation meter (the bar graph at the Phase meter’s bottom) indicates a stereo signal’s mono compatibility. This was of crucial importance when mastering for vinyl, because it could indicate if there were out-of-phase audio components in the audio that could possibly cause the stylus to jump out of its groove. These days, it’s largely a stereo world but it’s still important to check for mono compatibility—after all, when listening to speakers, you don’t have perfect stereo separation. You’ll usually monitor correlation in the master bus, but for individual tracks, it can indicate whether (for example) a signal processor is throwing a track’s left and right channels out of phase.

The Correlation meter reading spans the range between -1 (the right and left channels are completely out of phase, with no correlation) and +1 (the right and left channels are identical, and correlate completely). With most mixes, the bar graph will fluctuate between 0 and +1.

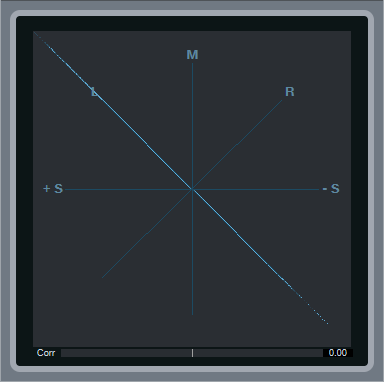

Mono Readings

If the Phase meter displays a single vertical line, then the left and right channels are identical, and the track is mono. The Correlation bar graph meter at the bottom confirms this with its reading of 1.00, which means the left and right channels correlate completely—in other words, they aren’t just similar, but identical.

Left and Right Readings

If there’s a single, diagonal line on the L axis, that means that all the signal’s energy is concentrated in the left channel. Similarly if there’s a single, diagonal line on the R axis, then all the signal’s energy is concentrated in the right channel. If you pan a track where the left and right channels are identical (as shown by the Correlation meter displaying 1.00), then the line will move from one channel to the other.

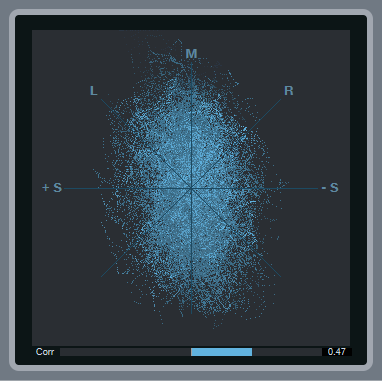

Stereo Signals

With stereo, you’ll see an excellent visual representation of how much the signal extends into the stereo field. The vertical size indicates the level. As you pan the signal left or right, the stereo field will become narrower around the line that moves from left to right until at one extreme or the other, you’ll see only a diagonal line on the L or R axis.

Note the correlation meter is showing +0.47. This means that there’s about an equal amount of similarity between the left and right channels as there are differences, but nothing is out of phase.

Mid-Side Encoded Audio

With Mid-Side encoded audio, you’ll see amplitude around the L and R axes, as well as along the M axis. Because the L signal is the center and the R signal the sides, you’ll see a lot more level along the L axis. Also, note the Correlation meter setting of 0.00—this means that there’s no similarity between the right and left channels, which is what you’d expect with a Mid-Side encoded signal.

Binaural Pan Signal

Studio One’s Binaural Pan processor widens the stereo image so that there’s much more energy in the right and left sides than in the center; this image shows what happens when you set the widening to maximum. Compare this to the reading for stereo signals—you can see that in this case, the energy extends further out to the right and left. Furthermore, the Correlation meter shows that there are no significant similarities between the right and left channels, which is a result of the Binaural Pan processor being based on Mid-Side processing.

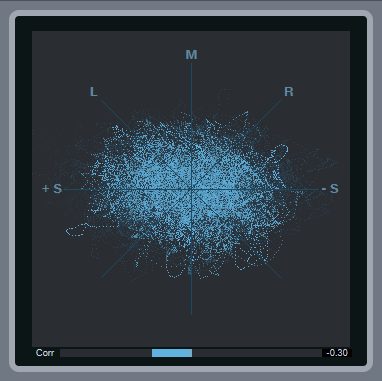

Phase Issues

Here, the Correlation meter shows a negative number, which means there are out-of-phase elements within the stereo mix. Occasional negative blips aren’t a problem, but if the Correlation meter spends a substantial amount of time to the left of 0, then there’s a phase issue that will interfere with mono compatibility.

Friday Tips: Create the “Barberpole” Audio Illusion

The Shepard Tone (aka Barberpole) is an audio illusion where a tone always seems to keep rising (or falling). You may have heard it before—to build tension in music by Swedish House Mafia, Beatsystem, Data Life, and Franz Ferdinand, as the sound effect for the endless staircase in Super Mario 64, for the sound of constant acceleration for the Batpod in The Dark Knight and The Dark Knight Rises, at the end of Pink Floyd’s “Echoes” from the Meddle album, or in the soundtrack for the film Dunkirk in sections where the goal was to produce a vibe of increasing intensity. Check out the audio example, and you’ll hear how the tone just goes on forever.

Thanks to Studio One’s Tone Generator, it’s easy to produce a Shepard Tone loop—just follow the step-by-step instructions, in a song with the tempo set to 120 BPM.

- Insert the Tone Generator in the Input L+R insert section so that you can record its tone, and edit the Tone Generator generator’s settings as shown in the screen shot. The goal is the longest possible sine wave sweep from 20 Hz to 22 kHz.

- Start recording, then click the Tone Generator’s On button. After recording the file, trim the beginning and end respectively to just before and just after you can hear a tone, and add a short fade in and fade out.

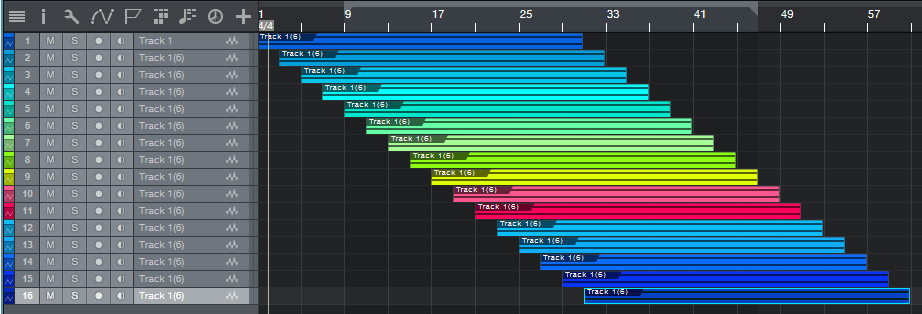

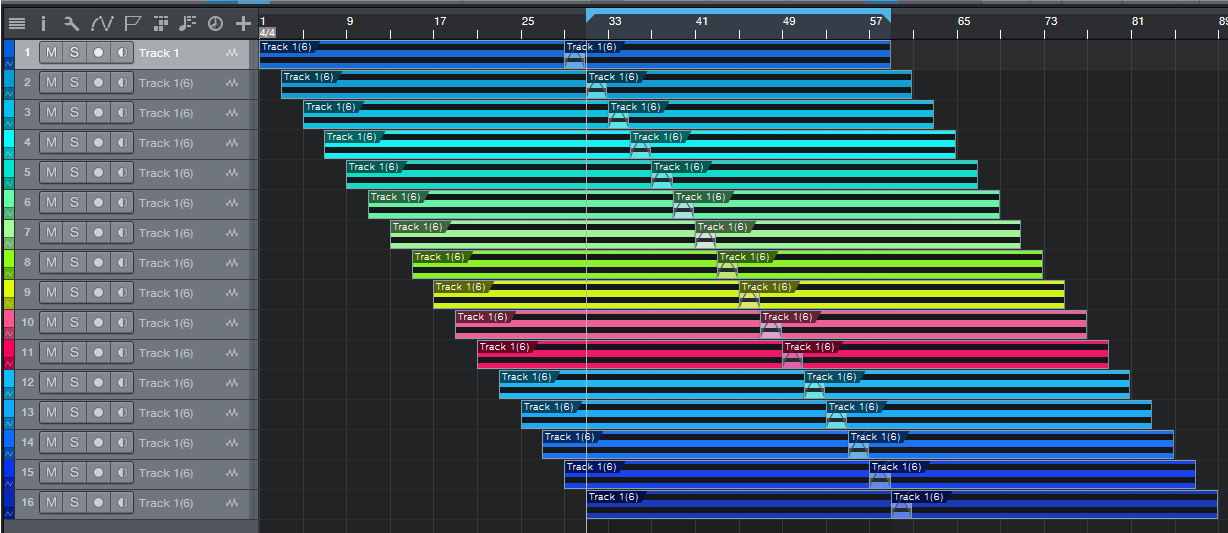

- As shown above, copy the track, and offset each track’s beginning by two measures compared to the track above it. Keep copying and offsetting until the start of the last track is at the same measure as the end of the first track.

- Now select all, and drag the entire group to the right so that there’s a bit of an overlap between the two groups. Select everything, then type X to turn the overlap into a crossfade with a linear curve. Next, create a loop that extends from the start of the lowest track to the end of the highest track.

- Choose Song > Export Mixdown, set the Export Range to Between Loop, and under Options, check Import to Track and Close After Export. Solo the mixed track, and play it—you’ll hear a continuously rising tone. Now we need to turn it into a loop.

- Follow the instructions in the July 27 Friday Tip of the Week on how to create pads that loop perfectly. The above screen shot shows the basic concept; Track 1 shows the first steps. Copy the clip, move the copy to the right so it overlaps the last four measures of the original clip, and then crossfade the overlap with a linear crossfade.

- Track 2 in the screen shot shows the next step. Bounce the two clips together, then split at the end of measure 4 to remove the first four measures, and at the end of the crossfade to remove everything after the crossfade. Loop the section that remains, and you have your never-ending upward Shepard Tone, as a glitchless loop. Note that when you bring it into a project, don’t stretch it to conform to tempo—there is no tempo. And if you want it to go on forever…just keep typing D!

Bonus Tips:

- I recommend adding a Pro EQ—reduce the high frequencies somewhat with the HC (High Cut) filter, and boost the low frequencies with a bit of a shelf, to increase the illusion’s effectiveness.

- The “classic” Shepard Tone requires that the tones be one octave apart. However, offsetting them by 2 measures at 120 BPM seems close enough.

The Virtual “How Does It Sound in a Car?” Tester

This tip is for those who won’t sign off on a mix until they’ve heard it in a car. There may be a scientific reason why this is beneficial: Noise tends to mask sounds, so if one instrument you want to hear gets lost in the noise and another jumps out, try a mix that raises and lowers those levels, respectively.

The ear doesn’t discriminate level differences as accurately as pitch differences, so without noise masking a sound, the level may seem okay. But as soon as you mix in noise, an important sound may disappear. If you increase the level just a bit so you can hear it, when you remove the noise there’s a very good chance you’ll like the new level setting better. Think of this as doing something similar to compression, but without applying any actual dynamics. You’re just making sure that the levels needing parity, have parity.

Of course this doesn’t mean you want everything jumping out of the noise—those tambourine and shaker parts are probably just fine as they are. The main sounds to listen to here are vocals, leads, drums, and bass, as well as their relationship to each other.

This also doesn’t mean you should mix consistently with noise, as it will bias your hearing (and besides, it’s truly annoying). I add noise in with a mix as a last diagnostic step. If the mix has sounded fine up until then and passes this final test, I consider it ready to master. And I don’t need to go driving anywhere, either.

Setup

Just follow the steps, and you’ll be good to go.

- Create a stereo audio track, and insert the Tone Generator effect. Turn the track’s fader all the way down.

- Choose Pink Noise as the waveform.

- Click On to start generating noise.

- Turn up the track’s fader to add noise to the mix.

One very cool aspect of the Tone Generator’s noise is that it’s true stereo where the left and right channels don’t correlate, so you don’t get any center channel buildup (as would happen with a mono noise signal).

As to how much noise to add, it’s kind of like maximizing. Set it 6 dB below the mix’s peaks, and you’ll hear what occupies the upper 6 dB of dynamic range. Set it 12 dB below the mix’s peaks, and you’ll hear what’s in the upper 12 dB of dynamic range. This isn’t an exact spec per se, but it provides a rough standard of comparison.

As crazy as this idea sounds, try it sometime and tweak your mix. Then turn off the noise, take a short break so your ears get acclimated back to normal hearing, and then check the mix again. I won’t be surprised if you hear an improvement!

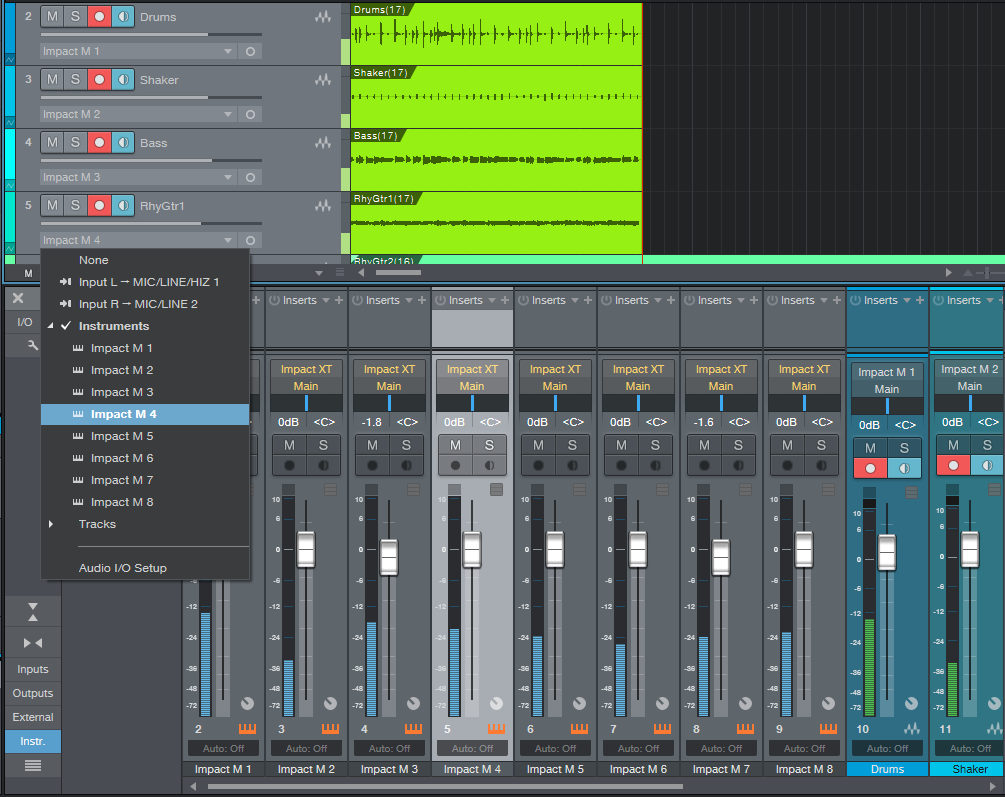

Songwriting with Impact XT

This tip is for those of you who didn’t see my Studio One workshop at Sweetwater GearFest 2018, were turned away because of that pesky fire marshal’s rules about crowds, or who didn’t realize Studio One 4 has some pretty advanced looping capabilities—as well as the ability to trigger pitch transpositions for loops.

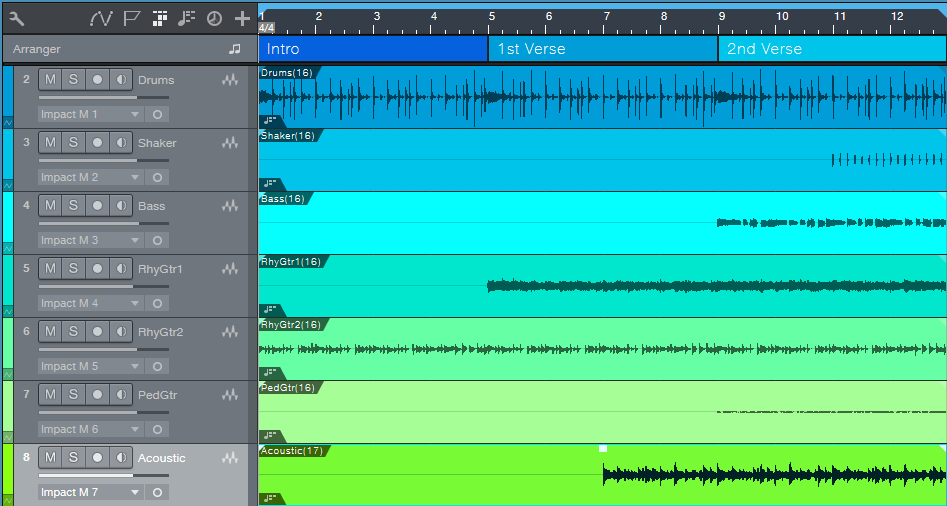

With Impact XT, you can load loops on pads, and then trigger them (on and off) in real time via MIDI notes. Assign each output from an Impact XT pad to a track input (in the screen shot, Track 5 is recording the output of Impact XT M4), set all the tracks to record, and you can record the results of your improvisations.

The following screen shot shows the results of recording the first part of a potential song. Note how some tracks have sounds that extend the length of the recording, while other tracks had their sounds brought in at specific times by triggering an Impact XT pad.

This by itself is pretty cool, because you can weave loops in and out to create an arrangement. The song goes longer than this, but the above shows what you’re hearing in the following audio example. Granted, it’s not much of a song—it just kinda drones on and on. But keep reading…this is just the start.

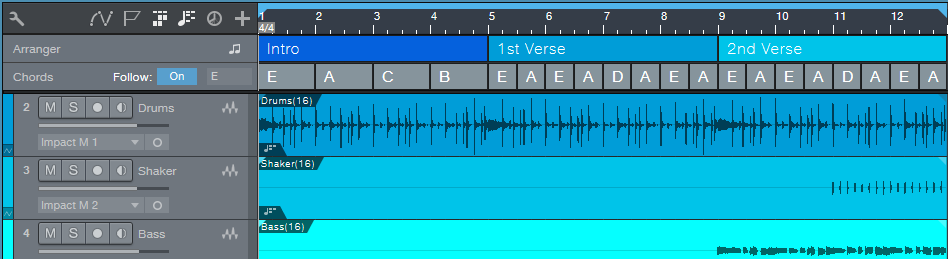

The process becomes far more interesting when you bring the chord track into play, because you can transpose the loops to create a chord progression that becomes the basis for a song. All the tracks, even the drums, were set to follow the chord track. Listen to how although some of the original loops added a fourth to the tonic, when this was synched to the chord track, all of the loops followed a tonic-to-fourth chord progression. In other words, it wasn’t just one loop adding a fourth, but the entire song transposing to the fourth. We also gained an intro; here’s the chord progression that was used.

And here’s what the chord progression sounded like after harmonic editing. The major difference is in the intro, and transposing to D to kick off the second half of each verse.

Working this way can be very inspirational because you can create a basic arrangement with loops, and then use the Chord Track to create a chord progression. Although PreSonus is careful to point out that Harmonic Editing is more for “prototyping” songs and they expect that you’ll want to replace the “scratch” parts, I’ve found that many times the scratch parts end up being keepers—and I gotta say, I love what happens when you tell drums to follow the chord track!

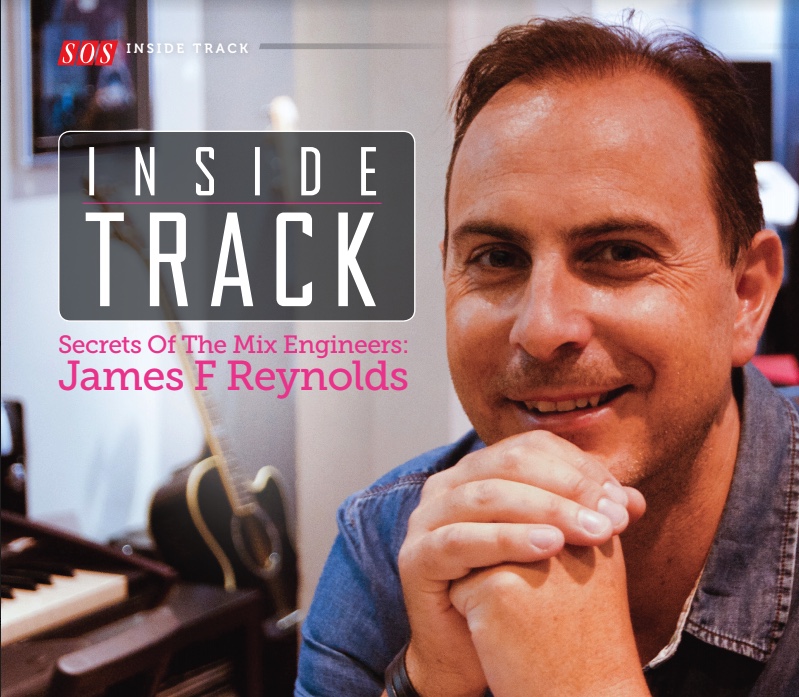

Studio One 4 User, James Reynolds, at the Top of the Charts!

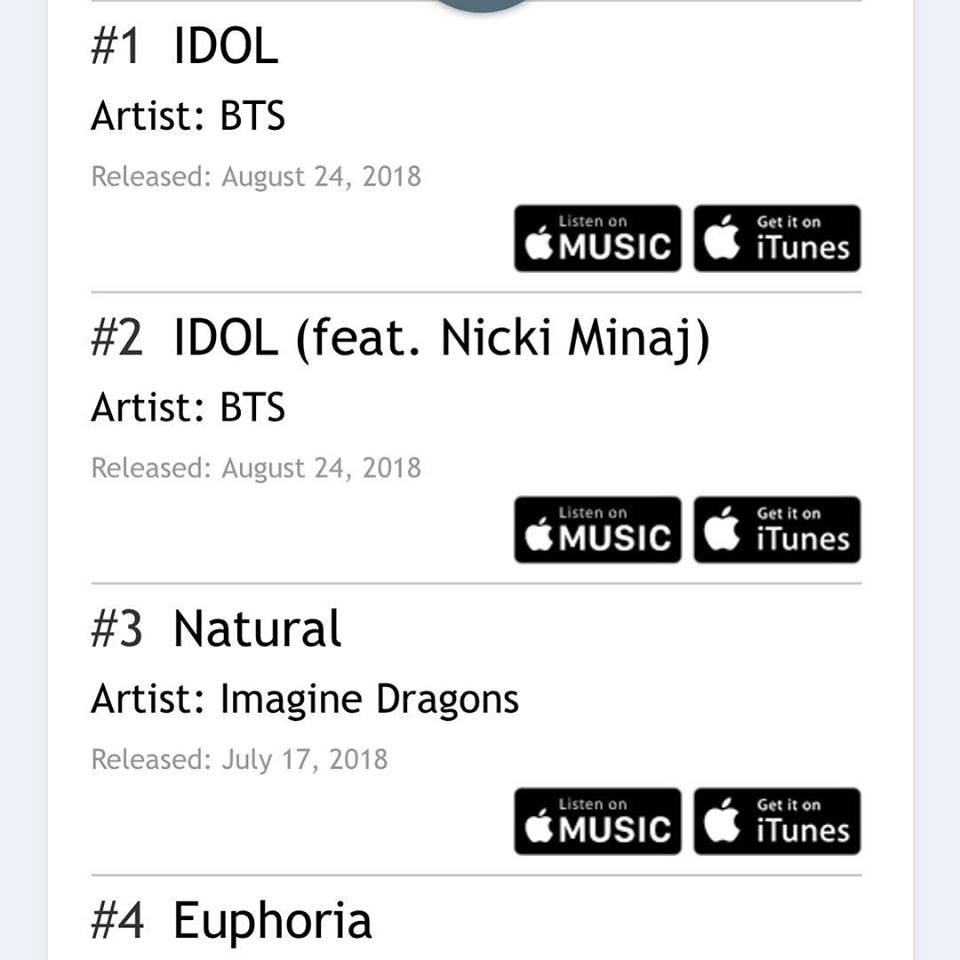

Currently sitting in the no.1 and no.2 slot on the USA iTunes Charts are two songs mixed by mix engineer, music producer and songwriter James Reynolds who also is a Studio One user!

As a huge fan of the DAW, Reynolds worked with us on the development of the new Studio One 4, and it’s his go-to DAW for many reasons.

Reynolds was recently interviewed for Sound on Sound Magazine. Check out some of the article here. Here are just a few things he had to say about Studio One:

“I was on Cubase for a while, and then I switched to Logic. I stayed in Logic for a long time, rather than moving to Pro Tools, because I found Logic more creative. But when I discovered Studio One I really liked it, and today it is absolutely perfect!”

“Pro Tools and Studio One are very similar, because Studio One is designed to make it very easy to convert to for Pro Tools users, who would find it a piece of cake. Where it differs is in the drag‐and‐drop workflow, which is super‐fast. You have a sidebar with all your plug‐ins listed in your folders, and you just pull a plug‐in on the channel or the bus, and it will set up the routing for you. It is designed to be super‐quick. It has also taken a leaf out of Ableton’s book, so all your samples can be previewed real‐time and will automatically loop in time. Plus it has gone next level, for example in that you can create splits of your plug‐in signals within your channels. So let’s say you have a lead vocal, and you want to do a parallel bus for it within that channel, you do the split inside the plug‐in, and this gives you a lot of control very easily. It is all very well thought‐out and the automation is fantastic, and so is the MIDI.”

Here’s more on what he has to say on Studio One. He’s basically the expert.

One more thing…. BTS’s latest release “IDOL” mixed by James, now holds the record for the biggest music video debut in YouTube’s history with over 45 million views in the first 24 hours! So that’s awesome.

Huge congrats to James and we’re so stoked for your success! Keep up with his success here.

Join the Studio One family here!

Friday Tip of the Week – EZ Squeez: the One-Knob Compressor!

Sometimes you just want a compressor that’s quick and easy. Maybe you’re tracking and need to compress the vocals, or hear what the bass will sound like when you add some compression on mixdown. But you know what happens—you adjust the threshold, and then the ratio, but now realize you need to re-adjust the threshold, which means the output gain needs adjusting…and maybe the knee…

If you have a bunch of ready-to-go presets, great. But here’s another option: The EZ Squeez compressor. It uses an FX Chain macro to alter six compressor parameters at once, so that a single knob sweeps from no compression, to some compression, to compression that’s more like a guitar sustainer stompbox. Although there’s a downloadable preset, I’d recommend reverse-engineering this to learn the power of the FX Chain’s Macro Controls. The principles used in this FX Chain apply to many other processors.

Figure 1: Three different Macro Control settings.

Figure 1 (top) shows the compressor settings with the EZ Squeez knob turned all the way counter-clockwise (minimal compression). As you turn up the EZ Squeez control, the Ratio, Release, and Gain increase, while the Threshold, Knee, and Attack decrease. The middle image shows the EZ Squeez knob turned up about 60% of the way. Turned up all the way, the parameter values become more extreme, as shown in the lower part of the screen shot.

Figure 2: (Top) Macro Controls parameters and (bottom) Macro Controls interface.

Figure 2 shows the Macro Controls. Rather than expose the control settings, it’s easier just to download the Multipreset, and then click on the curves for yourself. Note the curves on the Gain and Release parameters. Given that there’s only one node on the curve you can’t get too sophisticated, but these are close enough to give a fairly even response as you move the knob from fully counter-clockwise to fully clockwise.

Because compressors are so dependent on the input signal level, I did cheat on the “one-knob” concept and added an input level control. This allows trimming the input level so that it falls in the compressor’s “sweet spot.” There’s also a bypass button so you can compare the compressed and uncompressed sounds.

As to applications, you’ll probably find that EZ Squeez knob settings of 30% to 65% will work for a variety of signal sources. Past that point, the compressor gets into a more extreme territory that pumps mixed drums, and acts more like a sustainer for guitar. But it’s easy enough to find what works the best—just turn the knob until the compression sounds right. After all, that’s the whole point!

Download the EZ Squeez.multipreset

Friday Tip: Delay-Free Stereo from Mono

After a recent tip on how to extract two mono tracks from a stereo track, one of the comments asked for how to convert mono into stereo. Well, we aim to please…so here’s one option.

A common way to create stereo from mono is by duplicating the track, delaying one of the tracks compared to the other, and panning them left and right. However, this approach has two problems. First, you might not want a delay. Second, when you collapse the signal back to mono, there will likely be partial cancellation due to phase differences. The method we’ll cover here not only produces stereo imaging from a mono source, but collapses perfectly to mono. It works with pretty much any instrument, but is most effective with instruments that play chords (for example, try this on acoustic guitar—it works well).

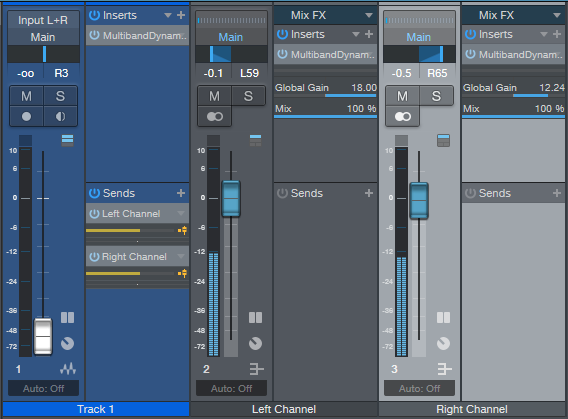

Console Setup

Create two buses. One of these will become the left channel, and the other, the right channel. In your mono source track, create two pre-fader sends (one for each bus). Turn down the mono source’s fader.

Multiband Dynamics Setup

Insert a Multiband Dynamics into one of the bus inserts. Solo the bus with the Multiband Dynamics. Click on “Edit All Relative” and set the Ratio control to 1.0. This will set all bands to a ratio of 1.0, which converts the Multiband Compressor into a multiband EQ.

Play the track you want to convert to stereo. Solo each band in the Multiband Compressor, and adjust the frequency sliders to divide up the frequency response evenly over the five bands (the screen shot shows frequencies selected for dry electric guitar). Mute bands 1, 3, and 5.

Next, drag the Multiband Dynamics into the other bus’s Inserts slot. For this bus, mute bands 2 and 4 instead of bands 1, 3, and 5, then pan the two buses left and right. Now the frequency responses are equal and opposite for the two buses. Voilà! Stereo! (Note that you probably don’t want to pan the buses too far to the left and right, because the stereo effect will be unrealistically exaggerated—as in the audio example. But it does get the point across.)

We’re not done yet, though. The levels of the two buses will be fairly low because with only two or three bands, the output level will be down quite a bit. Turning up the bus faders may be sufficient to compensate, but if not, turn up the Multiband Dynamics processors’ master Gain controls (not the per-band Gain controls). Feel free to play around with the pan and Gain controls to achieve the desired sonic balance. Also, no law says you need to mute every other band. For example, you might want a bassier sound on the left by muting the three upper bands, and a brighter sound toward the right by muting the two lower bands.

Finally, note that when you toggle the master bus from stereo to mono, the sound collapses to mono without any funky phase interactions. Done!